Abstract

Understanding health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents, during a pandemic and afterwards, aids in understanding how circumstances in their lives impact their well-being. We aimed to identify determinants of HRQOL from a broad range of biological, psychological, and social factors in a large longitudinal population-based sample. Data was taken from a longitudinal sample (n = 1843) of children and adolescents enrolled in the prospective school-based cohort study Ciao Corona in Switzerland. The primary outcome was HRQOL, assessed using the KINDL total score and its subscales (each from 0, worst, to 100, best). Potential determinants, including biological (physical activity, screen time, sleep, etc.), psychological (sadness, anxiousness, stress), and social (nationality, parents’ education, etc.) factors, were assessed in 2020 and 2021 and HRQOL in 2022. Determinants were identified in a data-driven manner using recursive partitioning to define homogeneous subgroups, stratified by school level. Median KINDL total score in the empirically identified subgroups ranged from 68 to 83 in primary school children and from 69 to 82 in adolescents in secondary school. The psychological factors sadness, anxiousness, and stress in 2021 were identified as the most important determinants of HRQOL in both primary and secondary school children. Other factors, such as physical activity, screen time, chronic health conditions, or nationality, were determinants only in individual subscales.

Conclusion: Recent mental health, more than biological, physical, or social factors, played a key role in determining HRQOL in children and adolescents during pandemic times. Public health strategies to improve mental health may therefore be effective in improving HRQOL in this age group.

What is Known: • Assessing health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents aids in understanding how life circumstances impact their well-being. • HRQOL is a complex construct, involving biological, psychological, and social factors. Factors driving HRQOL in children and adolescents are not often studied in longitudinal population-based samples. | |

What is New: • Mental health (stress, anxiousness, sadness) played a key role in determining HRQOL during the coronavirus pandemic, more than biological or social factors. • Public health strategies to improve mental health may be effective in improving HRQOL in children. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children and adolescents are formed by the environment they live in and their social engagement with those around them. The assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) allows us to better understand how circumstances in their lives impact their well-being, especially during disasters like the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Many children and adolescents remain resilient over time or may recover rapidly. However, others may suffer from multiple stressors (e.g., illness, disruption of the family system, isolation, social separation from peers, and home confinement), thereby impacting their short- and long-term mental health and well-being [1]. Understanding HRQOL and building knowledge about physical, emotional, and social challenges that children and adolescents may have experienced during the pandemic will allow to raise public health awareness and build the foundation for action now and in future difficult periods that may evolve.

Various studies have shown that HRQOL in children and adolescents has worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic [2,3,4,5], though there is some evidence that it has at least partially recovered to prepandemic levels [6]. HRQOL is a complex construct, defined as a subjective perception that an individual has about the impact their health has on their life, involving not only biological factors (e.g., body mass index (BMI), or chronic health conditions) [7], but also psychological (e.g., stress, anxiety or depression) and social factors (e.g., family support, social integration, or family atmosphere) [8, 9]. In line with this bio-psycho-social construct [8], several studies have demonstrated positive associations between physical activity (PA) and HRQOL [10,11,12], as well as negative associations between BMI and HRQOL [13, 14]. Other studies have explored associations with screen time [15,16,17], sleep [18], self-esteem and emotions [19], parents’ education and family wealth [20], and nationality [21]. While determinants of HRQOL in children with a range of chronic health conditions have been previously studied, generally prior to the pandemic, fewer have sought to identify possible determinants of HRQOL in healthy children, often with small sizes [12, 15, 21]. Surprisingly, few studies took a global view on HRQOL in youth by trying to understand the influence of the broader bio-psycho-social construct on their well-being and teasing out which factors alone or in combination are most influential.

Using data from the Ciao Corona study, a prospective school-based cohort study of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), we aimed to identify determinants of HRQOL at the end of the pandemic, June 2022. Using conditional inference trees, we aimed to identify both individual determinants and patterns of determinants that indicate clusters of children and adolescents with similar HRQOL in a large longitudinal population-based sample.

Methods

Study

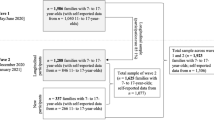

The data for this analysis come from the school-based longitudinal cohort study Ciao Corona [22], in which 55 randomly selected schools (primary school grades 1–6 and secondary school grades 7–9, ages 6–17 years) in the canton of Zurich, the largest canton in Switzerland of approximately 1.5 million inhabitants (18% of the total Swiss population), took part. Subjects (or their parents) were also asked to fill out a baseline questionnaire at the time of their first antibody test and to complete follow-up questionnaires on a periodic basis (July 2020, January 2021, March 2021, September 2021, and July 2022). The analysis set of this study included children and adolescents who had KINDL total scores in June 2022 and at least one questionnaire filled out earlier during the pandemic.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical committee of the canton of Zurich (2020-01336), and the study design has been published elsewhere [22] (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04448717). All participants provided written informed consent before being enrolled in the study. Results relating to lifestyle behaviors [23] and HRQOL [24] have been reported previously.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was HRQOL in June 2022, assessed using the KINDL questionnaire, filled out either by primary school students and parents together, or by students in secondary school on their own. KINDL is a reliable and valid measure of HRQOL in children and adolescents [25, 26], on a scale from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). It has 6 subscales, each from 0 to 100: physical, emotional, self-esteem, family, friends, and school. Several slightly different versions of KINDL are available, of which the parent version for children 7–17 years old was used [27]. Age group was determined by the highest grade level achieved during the study period. Children who were in sixth grade or lower were in the primary school group (having never gone to secondary school), while those who were in at least seventh grade by 2022 were in the secondary school group, even if they were still in primary school in 2020.

Possible determinants of HRQOL were pulled from questionnaires and categorized into three categories: biological, psychological, and social determinants, as has previously been described as a model for HRQOL [7, 8, 28, 29] (Fig. 1). Biological variables included sex (male, female, other), BMI, PA, screen time (ST), sleep duration, the presence of chronic health conditions, and symptoms possibly compatible with post-COVID-19 condition (also known as long COVID). BMI was calculated according to weight and height and compared with the standard Swiss population [30] to derive z-scores. BMI was then categorized as overweight if its z-score was 1 or higher. PA, ST, and sleep were recorded in hours per week, which were then compared with World Health Organization recommendations [31] (\(\ge 1\) h/day of PA, \(\le 2\) h/day of ST, and 9–11 h/night of sleep for 6–13 year olds or 8–10 h/night for 14–16 year olds). Chronic health conditions included asthma, celiac disease, neurodermatitis, type I diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy, joint disorders, and depression/anxiety. Possible post-COVID-19 condition [32, 33] was identified if participants reported any number of symptoms lasting 3 months or longer that might be related to a COVID-19 infection in seropositive participants.

Psychological variables included sadness, anxiousness, and stress that were taken from Health-Behaviour in School-Aged Children questionnaires [34]. For sadness, children were asked how often they felt sad or depressed in the last 6 months (daily, multiple times per week, once per week, once per month, seldom or never). For anxiousness, they were asked how often in the last 6 months they felt scared or anxious (same responses as for depression). For stress, parents were asked how they would assess the level of stress in the child’s life on a scale from 1 (no stress) to 6 (extreme stress).

Social variables collected were parents’ nationality (at least 1 Swiss parent vs other), parents’ highest education level (at least one with college prep high school or university vs compulsory high school or professional school or lower), the presence of household financial difficulties (yes/no), and change of parents’ working situation (reduction in or loss of work, vs no change), or change or loss of employment due to parents’ health [35].

Parents of participants were asked by email to fill out, with their child, a baseline questionnaire online at the time of their first serological test (June/July 2020, Oct/Nov 2020, Mar 2021, Nov/Dec 2021, June 2022). For the HRQOL, sadness, anxiousness, stress, and physical activity questions, parents were specifically asked to answer them together with their child. Thereafter, they were invited to fill out an online follow-up questionnaire at semi-regular intervals (Sept/Oct 2020, Jan 2021, Mar 2021, Sept 2021, Dec 2021, June 2022). While the baseline questionnaires asked a number of demographic details (e.g., parents’ nationality and education levels), there was significant overlap in content between the baseline and follow-up questionnaires. For data analysis, timepoints were grouped by year: 2019 (retrospective questions in the June 2020 questionnaire relating to the prepandemic period), 2020, 2021, and 2022. HRQOL was taken from the June 2022 questionnaire, while possible determinants were taken from 2019 to 2021. If multiple questionnaires existed for a subject in the same year with the same question, the mean or most frequent response was taken. The variables post-COVID-19 condition, household financial difficulties, or change in parent’s employment situation were coded “yes” if there were any relevant responses in the given year, and otherwise “no”. Sleep, PA, and ST were summarized as the proportion of responses meeting recommendations in the given year. Further details on the questionnaires used in Ciao Corona are found in Online Resource 1.

Statistical methods

KINDL scores were summarized as median [interquartile range (IQR)]. We used conditional inference trees [36, 37] estimated by binary recursive partitioning to identify possible determinants of HRQOL in children and adolescents. This statistical method identifies subgroups where stratifying by possible predictor variable produces a statistically significant difference in the outcome variable. For further details, see Online Resource 2. This procedure was repeated for the KINDL total score as well as for each of its subscales and stratified by age group (primary vs secondary school). As a sensitivity analysis, multiple imputation using chained equations was used to impute missing covariates [38] (m = 100), and then, recursive partitioning was used to identify significant predictors of HRQOL in each of the imputed datasets. We then counted how often each variable was included in the model selection procedure, with more important variables appearing more often than variables which are not determinants. All analysis was performed in R (R version 4.3.2 (2023–10-31)) using the packages partykit [36, 39] and mice [40].

Results

There were 1843 children and adolescents who had KINDL total scores in June 2022 and at least one questionnaire filled out since June 2020 (Table 1). Approximately 8% of children were overweight, and 76% had highly educated parents. KINDL total scores remained stable in the period 2020–2022 (median primary school in 2020 82.3 [IQR 77.1–86.5], in 2022 80.2 [74.0–85.4], and in secondary school 2020 79.2 [72.9–85.1] and 2020 74.0 [67.7–81.2]), but were somewhat lower in secondary school children than in those remaining in primary school (Online Resource 2: Fig. S1). Covariates considered to be potential determinants of HRQOL are displayed graphically in Fig. 1 and listed in Table 1 by age group and timepoint (2019, 2020, or 2021).

We first examined KINDL total score in primary school children, which ranged from 38 to 100 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 11.5 points. Most of the variation in KINDL total score in 2022 in primary school children was explained by stress, sadness, and anxiousness in 2021 (Fig. 2). Median KINDL total score in the identified subgroups ranged from 66 [IQR 57 to 73] (in those with frequent sadness, frequent anxiousness and moderate to high stress) to 83 [78 to 89] (in those reporting no stress), a difference which corresponded to 1.5 times the overall IQR. When repeating the analysis on each of the KINDL subscales (physical, emotional, self-esteem, family, friends, school), the same variables were generally chosen, along with sex and chronic health conditions (Fig. 3, see boxes denoted “P” or “P, S”). Notably, variables from 2021 were more often chosen than their 2020 counterparts.

Recursive partitioning tree for health-related quality of life (HRQOL, KINDL total score) in 2022 in primary school children. Identified determinants are stress, sadness, and anxiousness in 2021. Sadness and anxiousness could have occurred once per month (1M), once per week (1W), more than once per week (> 1W), or daily (D). Stress was considered on a five-point scale from 1 (no stress) to 4 (high stress). Other variables included in the model could not be used to create more homogeneous groups with respect to KINDL total score. For each subgroup, median KINDL total score, interquartile range (IQR), mean ± standard deviation, and sample size (n) are given

Overview of all variables identified as determinants of health-related quality of life assessed by the KINDL total score and its subscales: physical, emotional, self-esteem, family, friends, and school. “P” indicates variables identified for primary school only, “S” for secondary school only, and “P, S” for both primary and secondary school. Variables not shown were not identified for any of the subscales

Next, we examined KINDL total score in secondary school children, ranging from 33 to 99 with IQR = 13.5, where most of the variation was explained by stress, anxiousness, and sadness (Fig. 4). Median KINDL total score in the identified subgroups ranged from 68 [IQR 62 to 73] (among those with moderate to high stress and frequent anxiety) to 80 [73 to 87] (among those with no stress and infrequent sadness), a difference of 0.9 IQR. Repeating the analysis for secondary school children on each of the subscales, sex, PA, sleep, ST, and chronic health conditions were additionally identified as predictors of various subscales (Fig. 3, see boxes denoted “S” or “P, S”). However, none of these additional factors was identified as a determinant for overall HRQOL in secondary school children.

Recursive partitioning tree for health-related quality of life (HRQOL, KINDL total score) in 2022 in secondary school children. Identified determinants are stress, sadness, anxiousness, and self-rated health in 2021. Sadness and anxiousness could have occurred once per month (1M), once per week (1W), more than once per week (> 1W), or daily (D). Stress was considered on a five-point scale from 1 (no stress) to 4 (high stress). Self-rated health was rated as excellent, good, moderately good, or bad. Other variables included in the model could not be used to create more homogeneous groups with respect to KINDL total score. For each subgroup, median KINDL total score, interquartile range (IQR), mean ± standard deviation, and sample size (n) are given

As there is some uncertainty in recursive partitioning where models may not always choose the same factors in the presence of missing data, we repeated the model for total KINDL score 100 times each for primary and secondary school children (Fig. 5, Online Resource 2: Tables S4 and S5). For primary school children, the models most often included stress, anxiousness, and sadness. For secondary school children, the models generally included stress, sadness, and anxiousness, with PA included in 50% of the models.

Variables identified as determinants of KINDL total scores by recursive partitioning after multiple imputation (with 100 imputations). More frequently identified variables are of greater importance than those identified in few imputations. For example, meeting screen time recommendations was identified in only a few imputations and therefore did not appear to have a strong association with health-related quality of life, while meeting physical activity recommendations appeared to be of moderate importance related to health-related quality of life in secondary school students as it was identified in about 50/100 imputations

Discussion

Psychological factors from 2021 such as stress, sadness, and anxiousness were most predictive of HRQOL in 2022, in both primary and secondary school children from a longitudinal cohort of schoolchildren during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022. Determinants from 2021, rather than 2022, explained a difference in KINDL total score of 13–15 points out of 100 in clusters of children and adolescents with or without these factors. Our study suggests that social and biological factors did not play a role in determining HRQOL, especially in primary school children. Only for adolescents in secondary school were factors such as PA, sleep, ST, chronic health conditions, and nationality identified as determinants of individual KINDL subscales. These results show that a major part of HRQOL in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic was explained by mental health determinants from periods when restrictions were still in place (in 2021).

The existence of sadness, anxiousness, and stress as components of mental health led to a reduction in HRQOL of 12–15 points on a 0–100 scale in our sample, which is likely relevant from a public health perspective. To put this difference in context, it corresponds to or is even higher than the impact of family-based life changes, immigration status, or chronic health conditions such as asthma, headache, bipolar disorder, or hemophilia [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Considering that Switzerland had experienced one of the mildest restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the high socio-economic status of our sample, the impact of the pandemic on mental health in children and adolescents and on their HRQOL is expected to be much larger in a more disadvantaged population and countries with more severe confinements [48].

A number of publications have examined the relationship between HRQOL and a small number of mostly single factors in children, primarily before the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been observed that parental education and family wealth [20], as well as cardiorespiratory fitness, are correlated with HRQOL [15], along with PA [10,11,12], BMI [13], obesity [14], and ST [16]. Fewer studies have examined a broad range of potential factors and their association with HRQOL, and most were examined as single factors, especially since the onset of the pandemic [4, 49, 50]. These have identified psychological factors (self-esteem and emotions [19]), lifestyle factors (PA, sleep, ST, diet [18]), and sociodemographic factors (family education, poverty and race [51]; or unemployed parents, single parents, and non-western background [21]), as well as biological factors (disease burden, overweight, and chronic health conditions [21, 51]). While sex in our analysis was not identified as an important determinant of HRQOL after considering other factors, other publications have observed significant univariate associations between HRQOL and sex [25, 51, 52]. Our analysis remains one of few studies that examined a broad range of possible determinants for HRQOL in a pandemic setting.

If sadness, anxiousness, and stress are key determinants of HRQOL, the key public health implication is that reducing these three factors could improve HRQOL in children and adolescents. Improving mental health in children and adolescents likely requires individual, social, and community strategies in order to be effective [53]. School-based interventions [54] could include self-help strategies [53, 55], nature and green space [56,57,58], or strategies to improve lifestyle [16, 59]. It may be that stress, anxiousness, and sadness are only the nearest predictors in a pathway determining HRQOL. Changes to other factors may nevertheless improve mental health, thereby increasing HRQOL. It remains however unclear whether our findings can be generalized also to other settings beyond the pandemic.

This analysis has a number of strengths. It comprised a large sample (n = 1843) compared to similar studies on HRQOL and was based on a sample from randomly selected schools for a whole canton that is representative or the general population of schoolchildren in the canton of Zurich and for health behaviors in Switzerland [60] (median participation rates within each class of 50% were high compared to similar studies [61], see also [62, 63] as well as [64, 65]). Prospective data was collected across 2 years during a pandemic during which significant changes in life conditions throughout different levels of society (government, schools, families, peers) took place potentially affecting HRQOL. We based our concept on the bio-psycho-social health model, in line with a well-established conceptual model of HRQOL [7]. Stratification by age group accounted for differing behavior patterns and perceptions in primary school children versus adolescents in secondary school [52].

There are also several limitations. We did not measure HRQOL prior to the pandemic. While data collection for Ciao Corona did seek to examine changes in lifestyle and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, it did not a priori intend to explore determinants of HRQOL. Therefore, we have no information on some potentially interesting factors, for example, mental status and/or substance abuse or lifestyle of parents. Depression and anxiety were not based on clinical criteria, but on single questions taken from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey [66]. We cannot rule out some overlap between the KINDL items and the included potential determinants. Study participants were more likely to have Swiss nationality and more highly educated parents than the general population [67]. Had we been able to include also a more vulnerable, socially disadvantaged population, the study may have revealed an even stronger impact of mental health and other factors on HRQOL [20]. Additionally, data collection in our study leaned towards factors with possible negative impact [68, 69]. Future studies may improve data collection by including a better balance between positive and negative factors.

In conclusion, we observed the psychological factors such as stress, sadness, and anxiousness in 2021 were the main determinants of HRQOL in June 2022. Social and biological factors were generally not selected as determinants of overall HRQOL by our data-driven approach. A range of individual, family, community, and school-based strategies is likely needed to improve mental health and consequently HRQOL in children and adolescents during such difficult pandemic-related times and beyond.

Data availability

The data used for this analysis can be obtained by request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- ST:

-

Screen time

References

Kauhanan L, Wan Mohd Yunus W, Lempinen W, Peltonen K, Gyllenberg D, Mishina K et al (2023) A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:995–1013

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C (2022) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:879–889

Schmidt SJ, Barblan LP, Lory I, Landolt MA (2021) Age-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol 12(1):1901407

Dumont R, Richard V, Baysson H, Lorthe E, Piumatti G, Schrempft S et al (2022) Determinants of adolescents’ health-related quality of life and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos One 17(8):1–15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272925

Cortés J, Aguiar PMV, Ferrinho P (2023) COVID-19-related adolescent mortality and morbidity in nineteen European countries. Eur J Pediatr 182:3997–4005

Ehrler M, Hagmann CF, Stoeckli A, Kretschmar O, Landolt MA, Latal B, Wehrle FM (2022) Mental sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in children with and without complex medical histories and their parents: well-being prior to the outbreak and at four time-points throughout 2020 and 2021. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:1037–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02014-6

Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL (2005) Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh 37(4):336–42. Available from: https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x

Engel G (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286):129–136

Voll R (2001) Aspects of the quality of life of chronically ill and handicapped children and adolescents in outpatient and inpatient rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res 24:43–49

Wu LHAZ Xiu Yun AND Han (2017) The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: A systematic review. Plos One 12(11):1–29

Spengler S, Woll A (2013) The more physically active, the healthier? The relationship between physical activity and health-related quality of life in adolescents: The MoMo study. J Phys Act Health 10(5):708–715

Masini A, Gori D, Marini S, Lanari M, Scrimaglia S, Esposito F et al (2021) The determinants of health-related quality of life in a sample of primary school children: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(6), 3251.

Ul-Haq Z, Mackay DF, Fenwick E, Pell JP (2013) Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among children and adolescents, assessed using the pediatric quality of life inventory index. J Pediatr 162(2):280–286.e1

Nicholls L, Lewis AJ, Petersen S, Swinburn B, Moodie M, Millar L (2014) Parental encouragement of healthy behaviors: adolescent weight status and health-related quality of life. BMC Public Health 14, 369.

Borras P, Vidal J, Ponseti X, Cantallops J, Palou P (2011) Predictors of quality of life in children. J Hum Sport Exerc 6(4):649–656

Stiglic N, Viner R (2019) Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 9:e023191

Xiang H, Lin L, Chen W, Li C, Liu X, Li J et al (2022) Associations of excessive screen time and early screen exposure with health-related quality of life and behavioral problems among children attending preschools. BMC Public Health 22:2440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14910-2

Marques A, Peralta M, Santos T, Martins J, Gaspar de Matos M (2019) Self-rated health and health-related quality of life are related with adolescents’ healthy lifestyle. Public Health 170:89–94

Gaspar T, Ribeiro JP, de Matos MG, Leal I, Ferreira A (2012) Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: subjective well being. Span J Psychol 15(1):177–186

von Rueden U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Bisegger C, Ravens-Sieberer U, the European KIDSCREEN group (2006) Socioeconomic determinants of health related quality of life in childhood and adolescence: results from a European study. J Epidemiol Community Health 60:130–5

Houben-van Herten M, Bai G, Hafkamp E, Landgraf JM, Raat H (2015) Determinants of health-related quality of life in school-aged children: a general population study in the Netherlands. Plos One 10(7):e0134650

Ulytė A, Radtke T, Abela IA, Haile SR, Braun J, Jung R et al (2020) Seroprevalence and immunity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents in schools in Switzerland: design for a longitudinal, school-based prospective cohort study. Int J Public Health 65:1549–1557

Peralta GP, Camerini AL, Haile SR, Kahler CR, Lorthe E, Marciano L et al (2022) Lifestyle behaviours of children and adolescents during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland and their relation to well-being: An observational study. Int J Public Health 67:1604978

Haile SR, Gunz S, Peralta GP, Ulytė A, Raineri A, Rueegg S et al (2023) Health-related quality of life and adherence to lifestyle recommendations in schoolchildren during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the longitudinal cohort study Ciao Corona. Int J Public Health 68:1606033

Ravens-Sieber U, Erhart M, Wille N, Bullinger M (2008) Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents in Germany: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(1):148–151

Bullinger M, Brütt A, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, the BELLA study group (2008) Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17:125–32

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M (2000) KINDL questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents (revised version) manual. Available from: https://www.kindl.org/contacts/english/

Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM et al (2012) Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:134. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-134

Wilson IB, Clearly PD (1995) Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: a conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 273(1):59–65

Eiholzer U, Fritz C, Katschnig C, Dinkelmann R, Stephan A (2019) Contemporary height, weight and body mass index references for children aged 0 to adulthood in Switzerland compared to the Prader reference, WHO and neighbouring countries. Ann Hum Biol 46(6):437–447

WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour (2020) World Health Organization. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336656/9789240015128-eng.pdf

Stephenson T, Allin B, Nugawela MD, Dalrymple NR, Pereira SP, Soni M et al (2022) Long COVID (post-COVID-19 condition) in children: A modified Delphi process. Arch Dis Child 107:674–80

A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus (2021) World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

Psychische Gesundheit über die Lebensspanne (2016) Gesundheitsförderung Schweiz. Report No.: 03.0139.DE 04. Available from: www.gesundheitsfoerderung.ch/publikationen

Muralitharan N, Peralta GP, Haile SR, Radtke T, Ulyte A, Puhan MA et al (2022) Parents’ working conditions in the early COVID-19 pandemic and children’s health-related quality of life: The Ciao Corona study. Int J Public Health 67:1605036

Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A (2006) Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat 15(3):651–674

Venkatasubramaniam A, Wolfson J, Mitchell N, Barnes T, JaKa M, French S (2017) Decision trees in epidemiological research. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 14:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-017-0064-4

Sterne J, White I, Carlin J, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward M et al (2009) Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338:b2393

Hothorn T, Zeileis A (2015) Partykit: A modular toolkit for recursive partytioning in R. J Mach Learn Res 16:3905–3909. Available from: https://jmlr.org/papers/v16/hothorn15a.html

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45(3):1–67

Coker TR, Elliott MN, Wallander JL, Cuccaro P, Grunbaum JA, Corona R et al (2011) Association of family stressful life-change events and health-related quality of life in fifth-grade children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 165(4):354–359

Puder J, Pinto AM, Bonvin A, Bodenman P, Munsch S, Kriemler S et al (2016) Health-related quality of life in migrant preschool children. BMC Public Health 13:384. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-384

Kojima N, Ohya Y, Futamura M, Akashi M, Odajima H, Adachi Y et al (2009) Exercise-induced asthma is associated with impaired quality of life among children with asthma in Japan. Allergol Int 58(2):187–192

Milde-Busch A, Heinrich S, Thomas S, Kühnlein A, Radon K, Straube A et al (2010) Quality of life in adolescents with headache: results from a population-based survey. Cephalalgia 30(6):713–721

McGinty KR, Janos J, Seay J, Youngstrom JK, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA et al (2023) Comparing self-reported quality of life in youth with bipolar versus other disorders. Bipolar Disord 00:1–13

Bullinger M, von Mackensen S (2003) Quality of life in children and families with bleeding disorders. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 25:S64–S67

Kenzik KM, Tull SY, Revicki DA, Shenkman EA, Huang IC (2014) Comparison of 4 pediatric health-related quality-of-life instruments: a study on a Medicaid population. Med Decis Making 34(5):590–602

UNESCO (2022) Monitoring of school closures. Available from: https://webarchive.unesco.org/web/20220629024039/https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/

Papadaki S, Carayanni V, Notara V, Chaniotis D (2022) Anthropometric, lifestyle characteristics, adherence to the mediterranean diet, and COVID-19 have a high impact on the Greek adolescents’ health-related quality of life. Foods 11(2726)

Cheung MC, Yip J, Cheung J (2022) Influence of screen time during COVID-19 on health-related quality of life of early adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(17):10498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710498

Simon AE, Chan KS, Forrest CB (2008) Assessment of children’s health-related quality of life in the United States with a multidimensional index. Pediatrics 121(1):e118–e126

Michel G, Bisegger C, Fuhr D, Abel T (2009) Age and gender differences in health-related quality of life of children and adolescents in Europe: A multilevel analysis. Qual Life Res 18:1147–57

Wolpert M, Dalzell K, Ullman R, Garland L, Cortina M, Hayes D et al (2019) Strategies not accompanied by a mental health professional to address anxiety and depression in children and young people: A scoping review of range and a systematic review of effectiveness. The Lancet Psychiatry 6(1):46–60

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H (2017) School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 51:30–47

Town R, Hayes D, March A, Fonagy P, Stapley E (2023) Self-management, self-care, and self-help in adolescents with emotional problems: a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02134-z

Reece R, Bray I, Sinnett D, Hayward R, Martin F (2021) Exposure to green space and prevention of anxiety and depression among young people in urban settings: a global scoping review. J Public Ment Health 20(2):94–104

Bray I, Reece R, Sinnett D, Martin F, Hayward R (2022) Exploring the role of exposure to green and blue spaces in preventing anxiety and depression among young people aged 14–24 years living in urban settings: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Environ Res 214(4):114081

Tillmann S, Tobin D, Avison W, Gilliland J (2018) Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Commun Health 72(10):958–966

Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Cadenas-Sánchez C, Estévez-López F, Muñoz NE, Mora-Gonzalez J, Migueles JH et al (2019) Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 49:1383–1410

Institut für Epidemiologie, Biostatistik und Prävention der Universität Zürich (2014) Gesundheit im Kanton Zürich Band 1: Ergebnisse der Schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung 2012. Gesundheitsdirektion Kanton Zürich. Report No.: 19. Available from: https://www.gesundheitsfoerderung-zh.ch/publikationen/gesundheitsbericht

Sacheck JM, van Rompay MI, Olson EM, Chomitz VR, Goodman E, Gordon CM et al (2015) Recruitment and retention of urban schoolchildren into a randomized double-blind vitamin D supplementation trial. Clin Trials 12(1):45–53

Ulyte A, Radtke T, Abela IA, Haile SR, Ammann P, Berger C et al (2021) Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and clusters in school children from June 2020 to April 2021: Prospective cohort study Ciao Corona. Swiss Med Wkly 151:w30092

Ulytė A, Radtke T, Abela I, Haile S, Blankenberger J, Jung R et al (2021) Variation in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence across districts, schools and classes: baseline measurements from a cohort of primary and secondary school children in Switzerland. BMJ Open 11(7):e047483

Raineri A, Radtke T, Rueegg S, Haile S, Menges D, Ballouz T et al (2023) Persistent humoral immune response in youth throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: Prospective school-based cohort study. Nat Commun 14:7764. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43330-y

Haile SR, Raineri A, Rueegg S, Radtke T, Ulytė A, Puhan MA et al (2023) Heterogeneous evolution of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in school-age children: results from the school-based cohort study Ciao Corona in November-December 2021 in the canton of Zurich. Swiss Med Wkly 153(1):40035

Ambord S, Eichenberger Y, Jordan MD (2020) Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden der 11- bis 15-jährigen Jugendlichen in der Schweiz im Jahr 2018 und zeitliche Entwicklung: Resultate der Studie ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children’ (HBSC). Sucht Schweiz. Report No.: 113. Available from: https://www.hbsc.ch/pdf/hbsc_bibliographie_351.pdf

Statista Research Department (2021) Bildungsstand der Wohnbevölkerung im Kanton Zürich nach höchster abgeschlossener Ausbildung im Jahr 2021 Bildungsstand der Wohnbevölkerung im Kanton Zürich nach höchster abgeschlossener Ausbildung im Jahr. Available from: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1241630/umfrage/bildungsstand-der-bevoelkerung-im-kanton-zuerich/

Freire T, Ferreira G (2018) Health-related quality of life of adolescents: relations with positive and negative psychological dimensions. Int J Adolesc Youth 23(1):11–24

Lin XJ, Lin IM, Fan SY (2013) Methodological issues in measuring health-related quality of life. Tzu Chi Med J 25(1):8–12

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Samuel Gunz for his assistance with preparing an earlier version of the HRQOL and lifestyle data used here.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich This study is part of Corona Immunitas research network, coordinated by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+), and funded by fundraising of SSPH+ that includes funds of the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and private funders (ethical guidelines for funding stated by SSPH+ will be respected), by funds of the Cantons of Switzerland (Vaud, Zurich, and Basel), and by institutional funds of the Universities. Additional funding, specific to this study, is available from the University of Zurich Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK and MAP initiated the project and preliminary design. SK, TR, SRH developed the design and methodology. SK, TR, AU, AR, SR, GPP, recruited study participants, collected, and managed the data. SRH performed statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of its results and revised and approved the manuscript for intellectual content. SK and SRH had access to and verified all underlying data. The corresponding author SK attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland (2020-01336). All participants provided written informed consent before being enrolled in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Gregorio Milani

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haile, S.R., Peralta, G.P., Raineri, A. et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in healthy children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Pediatr 183, 2273–2283 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05459-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05459-w

Keywords

Profiles

- Sarah R. Haile View author profile

- Thomas Radtke View author profile