Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the working conditions of nurses, leading to a detrimental effect on their sleep quality. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the prevalence of poor sleep quality and its associated factors among nurses working in COVID-19 wards in Kermanshah, Iran. A total of 97 nurses were selected through simple random sampling from COVID-19 wards. Data was collected using a demographic information sheet and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods, including chi-square and multiple logistic regression, were used for data analysis. The results showed that 74.2% (n = 72) of the nurses experienced poor sleep quality. Significant associations were found between poor sleep quality and work experience (p = 0.045) as well as the type of work shift (p = 0.001). However, no significant relationships were observed between poor sleep quality and factors such as age, sex, body mass index, overtime hours per month, physical activity, or underlying diseases. The high prevalence of poor sleep quality among nurses working in COVID-19 wards underscores the necessity of implementing targeted interventions to address this issue. In this regard, in addition to periodic shift schedule changes and reductions in working hours, it is necessary to adopt purposeful measures to improve working conditions and enhance the physical and mental health of nurses. These measures may include providing sufficient human resources to reduce the workload and fatigue of nurses, appropriate scheduling of working hours, and the implementation of stress management programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor sleep quality is a prevalent concern among nursing professionals, with substantial implications for their physical and psychological well-being1,2. It has been linked to various adverse outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, hypertension, decreased job satisfaction, and absenteeism3,4,5,6. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the workload of nurses, potentially exacerbating their sleep quality issues6. In Iran, the nurse-to-population ratio is approximately 1.6 per 1000 population, which is half the global average7. This shortage of nurses, similar to other parts of the world, presents a major challenge8. The scarcity of staff has resulted in increased workloads and mandatory overtime, potentially worsening the sleep quality of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic9. The impact of this nursing shortage on the sleep quality of Iranian nurses working in COVID-19 wards is of great concern. Research consistently demonstrates that poor sleep quality among nurses hurts their perceived quality of life, overall health and well-being, and nursing productivity. Consequently, it poses a threat to patient outcomes and the quality of care provided10,11,12,13,14. While some studies have reported poor sleep quality among nurses during the pandemic, the existing literature on this topic has yielded inconsistent findings. For example, a study conducted in China (2022) among frontline nurses working in Fangcang hospitals reported average sleep quality2, while a study in Bahrain (2021) indicated that approximately 65% of nurses and doctors experienced poor sleep quality15. Additionally, a study conducted in Germany (2021) reported favorable sleep quality among nurses1. These conflicting findings suggest that the factors influencing sleep quality among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic may vary across different contexts and healthcare settings.

To address this gap in the literature, the current study aims to investigate the relationship between sleep quality and its potential determinants among Iranian nurses providing care in COVID-19 wards. By identifying the factors associated with poor sleep quality, this study can offer valuable insights for healthcare policymakers to implement necessary interventions aimed at improving the sleep quality of nurses working in COVID-19 wards. The study aims to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of poor sleep quality among nurses working in COVID-19 wards? (2) Which factors are associated with poor sleep quality among nurses employed in COVID-19 wards?

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Kermanshah, Iran, following the guidelines outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement16. The study utilized a descriptive and analytical approach to analyze the data.

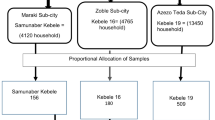

Sample and sampling method

The study was conducted at Golestan and Farabi hospitals, which are both located in the western province of Kermanshah, Iran, and admit COVID-19 patients. The target population for this study included all nursing staff employed at these hospitals. The sample size was determined to be 97 based on a desired accuracy level of 0.53, a variance of 3.56, and an error margin of 0.05 using the formula n = \(\frac{{\sigma }^{2}\times {{z}_{\alpha/2}}^{2}}{{d}^{2}}\). This estimation was based on the findings of a study by Han et al.17. To select the participants, a simple random sampling technique was used. The researcher obtained a list of nurses from the nursing offices of Golestan and Farabi hospitals and assigned numerical labels to them. The selection of samples was performed using a table of random numbers. Individuals who met the following criteria were included in the study: willingness to participate, possession of a Bachelor's degree or higher in nursing, and a minimum of four months of work experience in COVID-19 inpatient wards.

Data collection tool

The data collection instruments used in this study included the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and a demographic information sheet. The demographic information sheet consisted of eleven questions covering variables such as gender, age, marital status, weight, height, place of work, work experience in COVID-19 wards, type of work shift, monthly overtime hours, physical activity levels, and history of underlying medical conditions.

The PSQI is a standardized tool developed by Buysse et al. in 1989 for assessing sleep quality in the past month18. Its internal consistency has been evaluated using Cronbach's alpha, with reported estimates ranging from 0.77 to 0.8619,20. In Iran, the Persian version of the PSQI has undergone psychometric testing, revealing a Cronbach's alpha of 0.72, indicating good internal consistency21.

The PSQI consists of seven domains, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. It comprises a total of 14 questions, and participants rate their responses on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from "not during the past month" (0) to "three or more times per week" (3). The PSQI score ranges from 0 to 21, with a score of 5 or higher indicating poor sleep quality22.

Data collection method

To ensure representative sampling and minimize bias, a random sampling method was employed in this study. The researcher obtained a list of nurse names from the nursing offices of Golestan and Farabi hospitals and assigned numerical labels to each nurse. Samples were then selected using a table of random numbers. The selected nursing staff were approached by the researcher, who provided a clear explanation of the study's objectives and invited them to participate in the data collection process. The questionnaires were distributed to those who agreed to participate. If a nurse declined to participate, the next individual on the random list was approached. Once the questionnaires were completed, they were collected by the researcher.

To enhance data quality, the following measures were taken into account in this study: The study objectives were clearly stated for the participants, and their questions were addressed. Participants were provided with guidance on how to complete the questionnaires and respond to all the questions. It was ensured that their responses were confidential and the questionnaires were anonymous. The questionnaires were provided to the participants at a convenient time, and sufficient time was given for them to complete the questionnaires. Comprehensive training was provided to the data collector regarding the proper method of data collection and data entry into the software. Adequate statistical techniques were employed to handle missing data. Additionally, the research team regularly examined the data during the study to detect any discrepancies or unusual values. Any potential issues were addressed through collaboration within the research team23.

Data analysis

The data collected in this study were analyzed using version 18.0 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Descriptive statistics, including frequency distribution, mean, and standard deviation, were used for the initial analysis of the data. Inferential statistics, such as the multivariable logistic regression model, chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test, were employed to explore the relationships between variables. The chi-square test was used to examine the association between sleep quality among nursing staff and demographic characteristics such as age, sex, marital status, work location, shift type, monthly overtime hours, regular physical activity, and underlying medical conditions. Fisher's exact test was used specifically to examine the relationship between sleep quality and the variables of work experience and body mass index (BMI). Furthermore, a multivariable logistic regression model was employed to further analyze the significant variables identified in the chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. This model allows for the examination of the simultaneous effects of multiple variables on sleep quality. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The present study obtained approval from the ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, with the code IR.KUMS.REC.1399.851. Before participating in the study, all potential participants were provided with a clear explanation of the study's objectives, procedures, and potential risks or benefits. Any questions or concerns raised by the participants were thoroughly addressed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, indicating their voluntary agreement to participate in the study. The consent process ensured that participants were fully aware of their rights, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. To ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, their data and personal information were treated with strict confidentiality.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.KUMS.REC.1397.890. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All experimental protocols involving human subjects adhered to the relevant national/international/institutional guidelines or the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The nursing staff in this study had a mean age of 35.1 years (SD = 0.8). Female nurses comprised the majority of the sample, accounting for 72 individuals (74.2%), while more than half of the participants were single (n = 53, 54.6%). Regarding body weight, approximately 70.2% (n = 70) of the nurses had a normal BMI, while 27.8% (n = 27) were classified as overweight. In terms of work distribution, around half of the nurses (n = 50, 51.6%) were employed in the intensive care unit. Most nurses (n = 67, 72.0%) had a minimum of 10 years of work experience, with approximately 39.2% (n = 38) reporting working more than 60 h of overtime per month. The work shift for the majority of nurses (n = 70, 72.2%) was rotating, and a large proportion (n = 69, 71.1%) did not engage in regular physical activity. Among the participants, 63 nurses (65.0%) reported having underlying diseases (Table 1).

The findings of this study revealed that a significant proportion of nurses providing care in COVID-19 wards experienced suboptimal sleep quality. Specifically, 72 individuals (74.2%) reported poor sleep quality. When examining the age groups, a higher percentage of nurses below 35 years (n = 39, 73.6%) and above 35 years (n = 33, 75.0%) reported poor sleep quality. However, the difference between the two age groups was not statistically significant according to the chi-square test. Regarding gender, a majority of male nurses (n = 19, 76.0%) and female nurses (n = 53, 73.6%) reported poor sleep quality, and the chi-square test did not show a significant difference between them. The study also found that a higher proportion of married nurses (n = 38, 86.4%) reported poor sleep quality compared to single nurses (n = 34, 64.1%). This difference between the two groups was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.013) based on the chi-square test (Table 1). However, the logistic regression analysis indicated that while married nurses had 2.64 times poorer sleep quality compared to single nurses, this difference was not statistically significant (CI 95% 0.85–8.22) (Table 2). In terms of BMI, 70% (n = 49) of nurses with a normal BMI and 85.2% (n = 23) of overweight nurses reported poor sleep quality. However, Fisher’s exact test did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the two groups. According to the study findings, a majority of nursing staff working in both intensive care units (n = 39, 78.0%) and non-intensive care units (n = 33, 70.2%) reported poor sleep quality. However, based on the chi-square test, there was no significant difference observed between the two groups in terms of sleep quality. The results of the study also demonstrated that 67.2% (n = 45) of nursing staff with less than 10 years of work experience and 88.5% (n = 23) with more than 10 years of work experience reported poor sleep quality. This revealed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.038) (Table 1). Furthermore, the logistic regression analysis indicated that nurses with more than 10 years of work experience had 4.38 times poorer sleep quality than those with less than 10 years of work experience (CI 95% 1.03–18.64; p = 0.045) (Table 2). Based on the study findings, a higher percentage of nursing staff with rotating shifts (n = 60, 85.7%) reported poor sleep quality, while a majority of individuals with fixed shifts (n = 15, 55.6%) had good sleep quality. This finding suggests a statistically significant difference between the two groups based on the chi-square test (p = 0.001) (Table 1). The logistic regression analysis conducted in this study further revealed that nursing staff with rotating shifts had 6.46 times higher odds of experiencing poor sleep quality compared to those with fixed shifts, emphasizing a statistically significant difference between the two groups (CI 95% 2.16–19.31; p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Furthermore, the study results demonstrated that the majority of nursing staff who worked overtime for less than 60 h per month (n = 43, 72.9%) or more than 60 h per month (n = 29, 76.3%) reported poor sleep quality. However, the chi-square test did not indicate a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of sleep quality. Additionally, the findings of the study indicated that most nursing staff with underlying medical conditions (n = 45, 71.4%) and those without underlying medical conditions (n = 27, 79.4%) reported poor sleep quality. However, the chi-square test did not reveal a significant difference between the two groups in terms of sleep quality. Furthermore, based on the study findings, the majority of nursing staff, both with regular physical activity (n = 18, 64.3%) and without regular physical activity (n = 54, 78.3%), reported poor sleep quality. However, the chi-square test did not identify a significant difference between the two groups in terms of sleep quality (Table 1).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of poor sleep quality among nursing staff working in COVID-19 wards and identify factors associated with this issue. The findings of the study revealed that a significant proportion of nursing staff experienced poor sleep quality, aligning with previous research examining the sleep quality of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Previous studies conducted in Italy, China, and Turkey reported prevalence rates of sleep disorders among nurses to be 75.72%, 60%, and 61.9%, respectively6,13,22. These high prevalence rates of sleep disorders among nursing staff can be attributed to various factors. These factors include the fear of contracting and spreading COVID-19, separation from family, working overtime to compensate for nursing shortages, and the stress associated with the relatively unknown nature of COVID-1913,24. The findings of the current study suggest that nursing staff face significant challenges in maintaining good sleep quality, which can be attributed to multiple factors. These factors include the high patient volume, nursing shortages, long overtime hours, and the fear of transmitting the infection to their family members. These factors contribute to the overall burden on nursing staff and can hurt their sleep quality and well-being.

The results of the current study revealed a high prevalence of poor sleep quality among nursing staff in both age groups, with no significant difference observed between them. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted in China, which also found a high prevalence of sleep disorders among nurses in both age groups without a statistically significant difference13. It is worth noting that previous studies have consistently highlighted the negative impact of aging on sleep quality25,26. Considering the challenges associated with nursing and the risks posed by sleep disorders, implementing specific measures could prove beneficial. For instance, exempting older nurses from overtime, reducing working hours for experienced nurses, and offering early retirement options could help address this issue.

The study's findings indicated that a significant proportion of both male and female nursing staff experienced poor sleep quality, with no significant difference between the two groups. However, a systematic review reported that women were twice as likely as men to develop sleep disorders27. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in China, which found a higher prevalence of sleep disorders among female nurses compared to male nurses28. Similarly, a study conducted in Iran on healthcare workers, including nursing staff, reported a higher prevalence of sleep disorders among female nurses29. The higher prevalence of sleep disorders in women may be attributed to sex hormones27 and changes in the circadian rhythm during the menstrual cycle30.

The findings of the current study suggest that there was no significant difference in poor sleep quality between married and single nursing staff. This finding aligns with a study conducted in Mazandaran, Iran, which also reported no significant association between sleep quality and nurses' marital status31. However, a study conducted in China demonstrated that although the prevalence of sleep disorders was higher in single nurses compared to married nurses, the difference was not statistically significant13. These discrepancies in the results may be attributed to variations in occupational conditions and individual characteristics of the samples. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the challenging conditions associated with caring for COVID-19 patients adversely affected the sleep quality of both married and single nurses. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the working conditions of both groups and consider reducing their required working hours as a means to improve their sleep quality.

The findings of the current study revealed a statistically significant association between the work experience of nursing staff and their sleep quality. Nursing staff with more than ten years of work experience had a prevalence of poor sleep quality approximately 4.4 times higher than those with less than ten years of experience. This finding is consistent with a study in Iran (2014), which also reported a significant relationship between nursing staff's work experience and sleep quality32. However, two studies conducted among nursing staff in Iran and China reported no significant association between work experience and sleep quality31,33. In contrast to these studies, the present study found a statistically significant association between nursing staff's work experience and their sleep quality. These variations in findings may be attributed to differences in study design, sample size, or cultural and workplace factors. Nevertheless, to enhance the sleep quality of senior nurses, it may be beneficial to provide them with special amenities and benefits such as reduced working hours, exemption from shift work, and early retirement options. These measures could potentially contribute to improving their overall well-being and sleep quality.

The findings of our study indicate that both nurses with a normal BMI and overweight nurses experience poor sleep quality, but there is no statistically significant difference between the two groups. This finding aligns with a study conducted in the United States, which demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between sleep disorders and various BMI indices, including obesity, overweight, and underweight34. However, other studies have reported a significant correlation between poor sleep quality and obesity35,36. On the other hand, a meta-analysis has indicated that a low BMI is associated with a higher prevalence of poor sleep quality14. These inconsistencies in findings may be attributed to differences in sample characteristics between our study and previous research. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that sleep disorders, such as insomnia, can contribute to weight gain and obesity, which are linked to health risks such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes36. Therefore, it is crucial to improve the sleep quality of nurses in order to mitigate the physical risks associated with obesity and overweight.

Our study also did not find a significant relationship between the type of ward and the sleep quality of nursing staff, as a notable proportion of nursing staff working in both intensive and non-intensive care units experienced poor sleep quality. This finding aligns with a study conducted on Iranian nursing staff, which similarly reported no significant relationship between the type of ward and sleep quality37. Likewise, another study involving Iranian nurses found that the majority of nurses working in intensive and non-intensive care units had poor sleep quality without any significant difference31. Despite the potential higher workload and subsequent poorer sleep quality experienced by nursing staff in intensive care units, the challenges associated with managing patients with COVID-19 and the demands placed on nursing staff in all wards have negatively impacted their sleep quality. To address this issue, it is crucial to prioritize the motivation of nursing staff, reduce their workload by ensuring adequate staffing levels, and provide guidance on methods to enhance their sleep quality.

Furthermore, the study revealed a significant association between nursing staff working rotating shifts and a higher prevalence of poor sleep quality compared to those working fixed shifts, with a prevalence rate approximately 6.5 times higher. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating an increased likelihood of sleep disorders among nursing staff who work rotating shifts38,39,40. A study conducted in Japan also found that 94% of nurses who worked shift rotations experienced sleep disorders39. Similarly, a study involving Indonesian nurses reported that approximately 47% of those working rotational shifts had poor sleep quality41. Furthermore, a study conducted in Turkey (2018) indicated that nursing staff working night shifts were fourteen times more susceptible to sleep disorders compared to their counterparts working day shifts26. The primary cause of sleep disorders in nurses working rotating shifts is the misalignment between their circadian rhythm and work schedule42. This misalignment may be related to disrupted cortisol secretion patterns43,44. Therefore, implementing strategies such as periodically substituting rotating nurses with fixed nurses may prove effective in improving the sleep quality of nurses working rotating shifts.

Moreover, the study observed a significant prevalence of poor sleep quality among nursing staff who worked both less than 60 h of overtime per month and those who worked more than 60 h, with no notable statistical difference between the two groups. This finding is consistent with previous research highlighting a correlation between heavy workloads, fatigue, and reduced sleep quality among nursing staff4,45. Furthermore, a study conducted in Korea (2020) found that nurses working three shifts had poorer sleep quality compared to those working two shifts46. Similarly, a study from Bulgaria (2018) reported that nurses who worked more overtime hours per week and night shifts experienced poor sleep quality3. Additionally, a study conducted in China (2020) revealed that nurses with longer working hours had poor sleep quality28. To improve the sleep quality of nursing staff, healthcare administrators can consider hiring additional staff to reduce the need for nurses to work overtime. This intervention has the potential to alleviate their workload and promote better sleep quality.

Another important aspect to consider is that the majority of nurses experience poor sleep quality, regardless of whether they engage in regular physical activity three times a week or not. However, the current study did not find any significant statistical difference between the two groups. In contrast, previous studies have indicated a negative association between sleep quality and physical activity9,28,47. For instance, a study conducted in China (2020) demonstrated that nurses with insufficient physical activity had poor sleep quality28. Furthermore, a systematic review examining the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality revealed that out of 29 studies, physical activity was shown to improve sleep quality in the majority. However, four studies reported no association, and one study found that physical activity hurt sleep quality48. The evidence suggests that regular exercise can enhance sleep quality by preventing lifestyle diseases and reducing depression47. Therefore, promoting regular exercise among nurses and providing incentives such as covering sports club membership fees could be beneficial in improving their sleep quality.

One noteworthy finding in the present study was the lack of a significant statistical correlation between underlying diseases and sleep quality, with no notable statistical difference observed between nurses with and without underlying diseases. In contrast, a study conducted in Hong Kong reported a significant association between poor sleep quality and the presence of underlying diseases, particularly gastrointestinal disorders49. Although it is expected that underlying diseases may hurt the amount and quality of sleep for nursing staff, the absence of a correlation between sleep quality and underlying diseases in our study suggests the influence of other factors affecting the sleep quality of nursing staff. Nonetheless, nursing managers should implement appropriate strategies, such as reducing working hours and exempting nurses with underlying diseases from rotational shifts, to support their sleep quality.

The study findings indicate that approximately two-thirds of nurses working in COVID-19 wards experience poor sleep quality. This finding can have undesirable consequences in areas such as nursing practice, healthcare systems, and patient well-being. In terms of nursing practice, evidence suggests that poor sleep quality can subject nurses to unfavorable outcomes, including reduced job performance, cognitive impairments, decreased decision-making capacity, and increased nursing errors5,50. Such repercussions can pose serious risks to patient care and safety4. Additionally, undesirable sleep quality can lead to reduced efficiency and productivity within healthcare systems51. Naturally, nurses with poor sleep quality are prone to high levels of fatigue, exhaustion, and job dissatisfaction, which can result in decreased productivity, increased absenteeism, and a greater inclination to leave the profession52,53. Furthermore, poor sleep quality can impact patient well-being. The absence of restful sleep can diminish nurses' communication abilities and their attentiveness to patients' communication needs, leading to decreased patient satisfaction and a negative perception of nurses and the healthcare system54,55.

Limitations

The current study had several limitations. Firstly, data were collected through self-reporting, potentially introducing limitations to the accuracy of the findings. Although efforts were made to ensure privacy and confidentiality, self-reporting is prone to recall bias or social desirability bias, which could affect the accuracy and reliability of the reported sleep quality. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of this study inherently restricts the establishment of causal relationships between variables. To address this limitation, future research employing longitudinal designs is recommended, as it would offer a more comprehensive understanding of the temporal relationships among variables. Another inherent limitation of cross-sectional studies is the possibility of residual confounding or unmeasured variables that may influence the identified relationships. Finally, the relatively small sample size of the study might have impacted the precision and generalizability of the findings. Conducting future studies with larger sample sizes would increase the statistical power and enhance the external validity of the findings.

Conclusion

The current study findings indicate that 74.2% of nursing staff assigned to COVID-19 wards experienced poor sleep quality. These findings have significant implications for nursing practice, patient care, and the resilience of the healthcare system. Of particular concern is the higher prevalence of poor sleep quality among nursing staff working rotating shifts and those with over ten years of experience. To address this issue and enhance the sleep quality of nursing staff in COVID-19 wards, it is crucial to implement tailored interventions that consider the unique needs of these individuals. To enhance the sleep quality of nurses, it is possible to encourage them to utilize relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or listening to music before bedtime. Providing educational programs on sleep hygiene, with an emphasis on factors such as reducing the consumption of caffeinated beverages 1 h before sleep and maintaining a regular sleep schedule, can also contribute to improving sleep quality. Effective management policies, including implementing appropriate reductions in working hours based on work experience, incorporating short rest periods between shifts, limiting consecutive night shifts, and implementing periodic shift rotations, can further mitigate the negative effects of long or night shifts on sleep quality. By implementing these interventions, we can positively impact the well-being of nursing staff and improve the overall quality of patient care. Moreover, further research is necessary to delve deeper into the multitude of factors that may influence the sleep quality of nursing staff working in COVID-19 wards. The insights gained from this study contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by nurses and will effectively inform the development of necessary interventions to support their well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bernburg, M. et al. Stress perception, sleep quality and work engagement of German outpatient nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(1), 313 (2021).

Huang, L. et al. Nurses’ sleep quality of “Fangcang” hospital in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Cekova, I., Stoyanova, R., Dimitrova, I., Vangelova, K. Sleep and fatigue in nurses in relation to shift work. In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018) Volume II: Safety and Health, Slips, Trips and Falls 20: 2019 186–193 (Springer, 2019).

Ghasemi, F., Samavat, P. & Soleimani, F. The links among workload, sleep quality, and fatigue in nurses: A structural equation modeling approach. Fatigue Biomed. Health Behav. 7(3), 141–152 (2019).

Khatony, A., Zakiei, A., Khazaie, H., Rezaei, M. & Janatolmakan, M. International nursing: A study of sleep quality among nurses and its correlation with cognitive factors. Nurs. Adm. Q. 44(1), E1–E10 (2020).

Simonetti, V. et al. Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A large cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 30(9–10), 1360–1371 (2021).

The nurse-to-population ratio in Iran is half the global average.

Janatolmakan, M. & Khatony, A. Explaining the experiences of nurses regarding strategies to prevent missed nursing care: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 30(6), 2054–2061 (2022).

Doleman, G., De Leo, A. & Bloxsome, D. The impact of pandemics on healthcare providers’ workloads: A scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 79(12), 4434–4454 (2023).

Imes, C. C. et al. Wake-up call: Night shifts adversely affect nurse health and retention, patient and public safety, and costs. Nurs. Adm. Q. 47(4), E38–E53 (2023).

Park, E., Lee, H. Y. & Park, C. S. Y. Association between sleep quality and nurse productivity among Korean clinical nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 26(8), 1051–1058 (2018).

Sayilan, A. A., Kulakac, N. & Uzun, S. Burnout levels and sleep quality of COVID-19 heroes. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 57(3), 1231–1236 (2020).

Tu, Z., He, J. & Zhou, N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 99(26), e20769 (2020).

Zeng, L.-N. et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in nursing staff: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Behav. Sleep Med. 18(6), 746–759 (2020).

Jahrami, H. et al. The examination of sleep quality for frontline healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep Breath. 25, 503–511 (2021).

Grech, V. & Eldawlatly, A. A. STROBE, CONSORT, PRISMA, MOOSE, STARD, SPIRIT, and other guidelines–Overview and application. Saudi J. Anaesth. 18(1), 137–141 (2024).

Han, Y., Yuan, Y., Zhang, L. & Fu, Y. Sleep disorder status of nurses in general hospitals and its influencing factors. Psychiatr. Danub. 28(2), 176–183 (2016).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28(2), 193–213 (1989).

Duran, S. & Erkin, Ö. Psychologic distress and sleep quality among adults in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Progr. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 107, 110254 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Sleep disturbance and psychological profiles of medical staff and non-medical staff during the early outbreak of COVID-19 in Hubei Province, China. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 733 (2020).

Fard, Z. R., Azadi, A., Veisani, Y. & Jamshidbeigi, A. The association between nurses’ moral distress and sleep quality and their influencing factor in private and public hospitals in Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 9(1), 268 (2020).

Arumugam, A., Zadeh, S. A. M., Alkalih, H. Y., Zabin, Z. A., Hawarneh, T. M. E., Ahmed, H. I., Jauhari, F. S., Al-Sharman, A. Test-retest reliability of a bilingual Arabic-English Pittsburgh sleep quality index among adolescents and young adults with good or poor sleep quality. Sleep Sci. (2024).

Faraji, A., Karimi, M., Azizi, S. M., Janatolmakan, M. & Khatony, A. Evaluation of clinical competence and its related factors among ICU nurses in Kermanshah-Iran: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 6(4), 421–425 (2019).

Fernandez, R. et al. Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 111, 103637 (2020).

Karakaş, S., Gönültaş, N. & Okanlı, A. The quality of sleep of nurses who works shift workers. J. ERU Fac. Health Sci. 41, 17–26 (2017).

Tarhan, M., Aydin, A., Ersoy, E. & Dalar, L. The sleep quality of nurses and its influencing factors. Eurasian J. Pulmonol. 20(2), 78 (2018).

Morssinkhof, M. et al. Associations between sex hormones, sleep problems and depression: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 118, 669–680 (2020).

Dong, H., Zhang, Q., Zhu, C. & Lv, Q. Sleep quality of nurses in the emergency department of public hospitals in China and its influencing factors: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 18(1), 116 (2020).

Ghalichi, L., Pournik, O., Ghaffari, M., Vingard, E. Sleep quality among health care workers. Arch. Iran. Med. 16(2) (2013).

Meers, J., Stout-Aguilar, J., Nowakowski, S. Sex differences in sleep health. Sleep Health. 21–29 (2019).

Saberi, M., Momeni, B., Azizi, M. The quality of sleep among nurses in critical care units of educational-therapeutic centers of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 97–109 (2020).

Bahri, N., Shamshri, M., Moshki, M., Mogharab, M. The survey of sleep quality and its relationship to mental health of hospital nurses. Iran Occup. Health. 11(3) (2014).

Deng, X., Liu, X. & Fang, R. Evaluation of the correlation between job stress and sleep quality in community nurses. Medicine. 99(4), e18822 (2020).

Krueger, P. M. & Friedman, E. M. Sleep duration in the United States: A cross-sectional population-based study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 169(9), 1052–1063 (2009).

Escudero, C. P., Fernández, S. P., Bautista, L. R., Cruz, B. M. & García, F. G. Sleep quality, body mass index and stress in university workers. Revista Médica de la Universidad Veracruzana. 18(1), 17–29 (2018).

Park, S. K., Jung, J. Y., Oh, C.-M., McIntyre, R. S. & Lee, J.-H. Association between sleep duration, quality and body mass index in the Korean population. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 14(8), 1353–1360 (2018).

Salehi, K., Alhani, F., Sadegh, N. K., Mahmoudifar, Y. & Rouhi, N. Quality of sleep and related factors among Imam Khomeini hospital staff nurses. Iran. J. Nurs. Res. IJNR. 15(3), 98–109 (2020).

Ohida, T. et al. Night-shift work related problems in young female nurses in Japan. J. Occup. Health. 43(3), 150–156 (2001).

Roodbandi, A. S. J. et al. Sleep quality and sleepiness: a comparison between nurses with and without shift work, and university employees. Int. J. Occup. Hyg. 8(4), 230–236 (2016).

Valero-Cantero, I. et al. Intervention to improve quality of sleep of palliative patient carers in the community: Protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 19, 1–9 (2020).

Mendrofa, I., Goni, P. N. & Pakpahan, M. P D: The differences of sleep quality between nurses with two-shifts of work and nurses with three-shifts of work. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health. 24, 243–261 (2021).

Epstein, M., Söderström, M., Jirwe, M., Tucker, P. & Dahlgren, A. Sleep and fatigue in newly graduated nurses—Experiences and strategies for handling shiftwork. J. Clin. Nurs. 29(1–2), 184–194 (2020).

Auger, R. R. Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders. In An Evidence-Based Guide for Clinicians and Investigators (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020).

Dai, C. et al. The effect of night shift on sleep quality and depressive symptoms among Chinese nurses. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 435–440 (2019).

Bae, S.-H. & Fabry, D. Assessing the relationships between nurse work hours/overtime and nurse and patient outcomes: Systematic literature review. Nurs. Outlook 62(2), 138–156 (2014).

Chae, M. J. S. J. C. Comparison of shift satisfaction, sleep, fatigue, quality of life, and patient safety incidents between two-shift and three-shift intensive care unit nurses. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 13(2), 1–11 (2020).

Banno, M. et al. Exercise can improve sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 6, e5172 (2018).

Dolezal, B. A., Neufeld, E. V., Boland, D. M., Martin, J. L. & Cooper, C. B. Interrelationship between sleep and exercise: A systematic review. Adv. Prev. Med. 2017, 1–14 (2017).

Chan, M. F. Factors associated with perceived sleep quality of nurses working on rotating shifts. J. Clin. Nurs. 18(2), 285–293 (2009).

Habiburrahman, M., Lesmana, E., Harmen, F., Gratia, N. & Mirtha, L. T. The impact of sleep deprivation on work performance towards night-shift healthcare workers: An evidence-based case report. Acta Medica Philippina. 55(6), 650–664 (2021).

Bhatti, M. A. & Alnehabi, M. Association between quality of sleep and self-reported health with burnout in employees: Does increasing burnout lead to reduced work performance among employees. Am. J. Health Behav. 47(2), 206–216 (2023).

Alameri, R. A., Almulla, H. A., Al Swyan, A. H. & Hammad, S. S. Sleep quality and fatigue among nurses working in high-acuity clinical settings in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 23(1), 51 (2024).

Qin, A. et al. Educational degree differences in the association between work stress and depression among Chinese healthcare workers: Job satisfaction and sleep quality as the mediators. Front. Public Health. 11, 1138380 (2023).

Sagherian, K., Steege, L. M., Cobb, S. J. & Cho, H. Insomnia, fatigue and psychosocial well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of hospital nursing staff in the United States. J. Clin. Nurs. 32(15–16), 5382–5395 (2023).

Mohedat, H. & Somayaji, D. Promoting sleep in hospitals: An integrative review of nurses’ attitudes, knowledge and practices. J. Adv. Nurs. 79(8), 2815–2829 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all the nurses who generously participated in this research.

Funding

The study was funded by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences under Grant No. 990449.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J., A.N., and A.K. were involved in the study design. M.J. collected the data, while A.N. conducted the data analysis. M.J., A.N., and A.K. collectively wrote the final report and manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Janatolmakan, M., Naghipour, A. & Khatony, A. Prevalence and factors associated with poor sleep quality among nurses in COVID-19 wards. Sci Rep 14, 16616 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67739-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67739-7