Abstract

Agricultural activities in many sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries are subject to various risk factors that the COVID-19 compounds. Earlier studies on the effect of COVID-19 on smallholders neglect the issue of comparison with non-farm households. The study uses micro-level household datasets to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on household welfare, with a focus on farm households relative to their non-farm counterparts. We employed a binary probit model and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) approach and demonstrated that farm households witnessed important income reductions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. The study contributes to the design of evidence-based approaches to reducing farmers’ vulnerabilities to agricultural risks and pandemic-related shocks.

Article highlights

-

a.

Farm households witnessed significant income reductions during the COVID-19 period in Uganda.

-

b.

Most common coping strategies adopted by households amid the COVID-19 crisis were reliance on savings, and reducing food consumption.

-

c.

The study offers suggestions in designing evidence-based approaches to reducing farmers’ vulnerabilities to agricultural or pandemic-related shocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

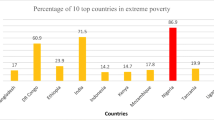

In most African countries, the agricultural sector continues to play a significant role as a driver of growth in employment and gross domestic product (GDP). In 2019, for instance, about 53% and 16% of total employment and GDP, respectively, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) were accounted for by the agricultural sector [1]. Despite the important developmental benefits of the agricultural sector, especially in SSA, the majority of people engaged in the sector are smallholders [2,3,4,5]. These smallholders are usually exposed to myriad risk factors including attacks by pests and diseases, market price uncertainties, and unstable weather conditions. Agricultural risks can be covariant/systematic (i.e. affecting a group of individuals or community) or idiosyncratic (i.e. affecting an individual farmer or household) and they may impact individuals or groups differently [6]. Farmers’ socioeconomic backgrounds (e.g. education, religion, age, gender, and farming practices) may influence their risk perceptions and the coping strategies they adopt [7, 8]. With the COVID-19 pandemic, these risks faced by farmers will be aggravated. This is because the COVID-19 pandemic and the related containment measures, including the imposition of national lockdowns and border closures, undeniably slowed economic activity in most African countries and worsened the plight of many low-income and vulnerable households, most of whom are engaged in agricultural activities [9, 10].

There are perceptions that farm households were more adversely impacted by the pandemic than non-farm households, partly due to their already low levels of income and limited diversification. However, there is little empirical evidence on this issue, especially from Africa. Studies have noted that before the emergence of COVID-19, agricultural activities in SSA were already affected by climate change, pests and crop diseases, and the outbreak of human diseases such as swine flu and Ebola, all of which contributed to low levels of food production and distribution [11, 12]. The fact that smallholder farming systems in Africa are generally labour-intensive and rainfall-dependent, and have weak linkages between input and output markets as well as limited post-harvest technologies and infrastructure, increased their vulnerability to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic [13] and the associated enforcement of social distancing, working from home, restricted transportation, and lockdowns [9, 14]. The imposition of movement restrictions would necessarily adversely affect labor-dependent farm operations such as planting, harvesting, threshing, and storage in Africa [15].

There were immediate measures to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on the agricultural sector. For example, when some local markets were closing down due to travel restrictions, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) helped connect farmers to buyers and provided seeds and fertilizer to farms in several countries in SSA [16]. Nevertheless, African farmers may struggle more to access and obtain quality seeds as a result of the pandemic than they did before [17]. Thus, there is a need for an assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on Africa’s agriculture. To this end, we ask the following research questions: (i) What was the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of farm versus non-farm households? and (ii) What mitigating measures or diversification strategies were adopted by farm households during the crisis? Unpacking these issues will contribute to our understanding of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on different types of households and the related mitigating measures.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section highlights the theoretical and empirical literature, including the conceptual framework of the study, while Sect. 3 presents a brief note on contextual issues related to diversification strategies and COVID-19 containment measures implemented in Uganda. Sections 4 and 5 present the data and methods of analysis, and the discussion of the empirical results, respectively; while Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Insights from the literature

2.1 Theoretical underpinnings and conceptual framework

Several health-related crises have disrupted economic activities in Africa in recent years, including the outbreaks of swine flu, Ebola, and SARS. These crises prompted scholars to study the impact of diseases on a global, national, or regional scale. Brahmbhatt and Dutta [18], for example, described the dynamics of SARS—behavioural responses and economic impacts as well as numbers of cases and deaths—using an economic epidemiological approach. They accounted for the indirect cost implications of the outbreak and spread of animal diseases, in particular the cost to smallholders and the agricultural value chain, especially livestock production.

The outbreak and spread of COVID-19 and its containment measures had the greatest impact on economic activities across the globe [19], and these shocks are complex in their effects due to both inter- and intra-sector transmission [20]. Government-imposed COVID-19 restrictions led to economic hardships in terms of reduced economic activities and earnings. This is thought to have had more severe impacts on the poor (who are mostly rural smallholder farmers) than on the rich, since smallholders who were already facing known agricultural risks—and adopting coping strategies to mitigate these–will have been hard hit by the unexpected pandemic outbreak and the impacts on both their farming activities and their livelihoods/welfare.

Our study focuses on how the pandemic has affected smallholder farmers in Uganda. In our conceptualization, we hypothesize that the impact of COVID-19 on agricultural activities is twofold: direct and indirect. The direct impact is related to the closure of farms and the interruption of the agricultural value chain since any curtailment of agricultural activities will necessarily have a direct impact on farm production [21]. The indirect aspect is related to other COVID-19 restrictions/containment measures that restricted agricultural activities. These include lockdowns that reduced farm working days and hours, border closures that affected fertilizer access, restricted transport that limited access to extension officers, social distancing that affected the number of laborers on farms, and other measures that affected farming activities in general (Fig. 1).

The outbreak of COVID-19 and its containment measures would therefore have had both direct and indirect effects on farm household welfare.Footnote 1 As shown in Fig. 1, direct containment measures such as farm closures and indirect measures such as lockdowns and restricted movement/transportation would add to the agricultural risks farmers usually face. With restricted transportation, farmers may not get fertilizer on time or at all, extension services would be limited, labour would be reduced, products due for harvest might not be harvested, land might not be cleared, and planting may cease. All these factors would directly affect food production and consequently would have an impact on welfare since reductions in farm production mean lower earnings for smallholders, who are already poor and have no alternative income. Low earnings would translate to a decline in livelihood and welfare for the smallholder.

2.2 Empirical literature

There is extensive empirical literature on COVID-19’s effect on farmers around the world. Our thematic review of the literature (agricultural risk and/or COVID-19 risk) revealed mixed results. In this sub-section, we present these results by looking at COVID-19 as a risk factor in agricultural activity and farm household welfare and the mitigation/diversification strategies they adopted amid the crisis.

There is a growing body of literature on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of farm households; again, however, the evidence therein is mixed. Hammond et al. [22] examined how farmers perceive the effects of the pandemic and the related containment measures on their livelihood and agricultural activities, as well as the coping strategies farm households adopted during the pandemic. They interviewed 9,201 smallholder farmers in seven countries (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Viet Nam, and Zambia) and found varied effects. They found that food purchasing, off-farm income, sale of farm produce, and access to crop inputs were all affected. The effects attributed to government restrictions were widespread and severe, as both off-farm and farm-based incomes were reduced, worsening economic and food security outcomes. In locations subject to more stringent restrictions, up to 80% of households had to reduce food consumption. Almost all households with off-farm incomes reported reductions and half to three-quarters of households (depending on the location) with income from farm sales reported losses compared with the pre-pandemic period. In locations with more relaxed containment measures in place, respondents reported less frequent and less severe economic and food security outcomes. The authors found that between 30% and 90% of households applied coping strategies in response to the pandemic during 2020.

In a similar vein, Siche [23] concluded that there is sufficient evidence to affirm that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an important effect on agriculture and the food supply chain, mainly affecting food demand and consequently food security, with an especially great impact on the most vulnerable populations.

Andrieu et al. [24] analysed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural systems and the decisions taken by policymakers in Burkina Faso, Colombia, and France to handle its direct and indirect effects. Their study was based on surveys conducted with farmers, traders, and extension staff. The authors identified contrasting state responses to the pandemic. In Burkina Faso, crop farmers and pastoral farmers in rural areas were not affected in their productive activities by COVID-19 lockdown measures, but their product marketing was affected as the demand from traders decreased during the lockdown. In contrast, in Colombia, the initial on-farm effects of COVID-19 resulted in the reorganisation of labour. For instance, organic vegetable producers near Cali had to reorganise their farm activities and labour to respond to higher demand for quality products, and coffee farmers also reported a reorganisation of farm activities linked to decreased contacts with the city (for off-farm activities or leisure) and more time available for farm activities. In France, the pandemic affected wine merchants as wine exports to Asia declined and, although in the short term, the pandemic had no discernible impacts on labour demand, cereal stocks, or marketing (except for cereals grown for fuel), vegetable production, and sales were affected in the short term and vineyards in the medium term. The authors added that in Colombia, despite the selling price of coffee being exceptionally high, production decreased by only 7%. Thus, the authors concluded that the measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 crisis did not lead to a drastic change in agricultural or farming systems.

Amankwah and Gourley [25] studied outcomes in five African countries and concluded that, in general, the share of households that had entered agriculture since the start of the pandemic was higher than those exiting. They also asserted that many households entered agriculture after the pandemic. In Malawi, for example, about 9% of households that were not involved in agriculture (either crop or livestock farming) before the pandemic went on to become involved afterward. In contrast, less than 2% of households that had been involved in agriculture pre-pandemic subsequently ceased to be. In Nigeria, the number of households that had gone into agriculture since the start of the pandemic was also higher (12%) than the number of those exiting (4%). The authors further found that 41% of households in Ethiopia, and 73% in Malawi, that had received income from agriculture in the last 12 months reported loss of income due to the pandemic.

Goswami et al. [26] explored the multiple pathways of present and future impact on smallholder agricultural systems created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors found that the pandemic has affected farming in the areas of input availability, credit access, produce marketing, and labor availability, among others. Coping strategies adopted by farmers included engaging families as labourers, exchanging labourers with neighbouring farmers, borrowing money from relatives, accessing food hand-outs, replacing dead livestock, early harvesting, and reclaiming water bodies. Thus, this present study provides further insight into the discourse using the case of Uganda.

3 COVID-19 containment efforts in Uganda

The first measures taken by African governments in response to the outbreak of COVID-19 were to restrict cross-border movement and limit foreign air travel [27]. Between 13 and 24 March 2020, 25 African countries imposed such restrictions. Almost all these countries also suspended the arrival of international flights, at least from countries particularly affected by the virus. Stricter (sanitary) border controls usually increase trading costs [28], and intra-African trade of agricultural products duly slowed [29]. The COVID-19 pandemic sparked an unprecedented decline in world trade (down by 15.5% in volume between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020), but an even more pronounced drop for Africa as a whole (down by 17.7%).

The Ugandan government imposed a nationwide lockdown on 31 March 2020 and ordered the closure of businesses other than those selling food to contain the pandemic. Restrictions on transport were imposed on the same date and tightened on 10 April, when social distancing and mandatory mask-wearing were also introduced [30, 31]. These measures had an impact on economic activities, similar to that seen in other jurisdictions. Even though Uganda recorded fewer COVID-19 cases than its comparator countries in the sub-region, the effect of the pandemic-related restrictions on economic activity and livelihoods was not inconsequential. Bouët et al. [29] estimated an income loss of about US$184 million (9.1% of monthly GDP) due to the slowdown in economic activities and job losses. The authors further suggested that about 65% of the total population experienced either partial or full loss of income. Thus, the pandemic had a severe impact on the economy, and consequently on living conditions and livelihoods, particularly in terms of agricultural activities.

As in many African countries, Uganda’s COVID-19-related restrictions harmed the supply of agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and agrochemicals. In particular, the closure of public transport services limited access to these inputs, since farmers (who mainly live in rural areas) could not collect supplies from the cities and towns, where most agricultural inputs are sold [13, 32].

4 Data and methodological approach

4.1 Data

To seek responses to our research questions, we drew on six rounds of the World Bank’s ‘High-Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) on COVID-19’ dataset for Uganda.Footnote 2 The HFPS contains detailed information on households’ economic activities before and during the pandemic—earnings and income—as well as detailed individual and contextual characteristics. In the immediate post-COVID round of the survey, respondents were asked the following questions:

Q1: ‘Since March 20, 2020, the day that schools were closed, has income from the activity increased, stayed the same, reduced, or become a total loss (no earnings)?’

Q2: ‘Compared with the average monthly income during the 12 months prior to COVID, is the household monthly income at the same level as before COVID, above the pre-COVID level, or below the pre-COVID level?’

However, in the subsequent rounds, question 1 was rephrased to reflect respondents’ perceived level of income loss in the month of the survey relative to the preceding month, as captured below:

Q1a: ‘Since the last call, has income from activity increased, stayed the same, reduced, or become a total loss (no earnings)?’

Using the responses to these questions, we create two alternative measures of income loss due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our first measure of income loss (inc_loss1) is binary and assumes a value of 1 if the household indicates that their income has reduced, or they have experienced a total loss in income or earnings, and 0 if otherwise. The second measure of income loss (inc_loss2) is binary and takes a value of 1 if the household indicates that their current monthly income is below the pre-COVID level and 0 if otherwise.

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for these variables and those for other key independent variables employed in the model of determinants of COVID-related income loss.

Over 94% of households experienced either a reduction in income or a total loss in income during the post-COVID period, while close to 68% of households had monthly incomes below the pre-COVID level. About 86% of households in the sample were engaged in agricultural activities as their main economic activity.

4.2 Methodof analysis

To estimate the determinants of COVID-induced income reduction, we employ the binary probit model, since the dependent variable is binary. Consequently, we follow the specification in Eq. (1):

\(\:{A}_{i}^{*}\) is the latent continuous response variable that indicates whether a household i experienced a reduction in income due to COVID-19. \(\:{Ind}_{i}\) and \(\:{Z}_{i}\) denote vectors of household- and farm-level/contextual factors, respectively, related to household i. The household-level covariates included in the estimations are the educational attainment of the household head, the head’s gender and age, the size of the household, and whether the household’s main economic activity is farming.Footnote 3 The farm/contextual variables are locality (rural versus urban), region, type of crop cultivated, nature of land ownership, and whether the farm is treated as a family business. \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) are vectors of coefficients to be estimated and is the intercept term. \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) is the standard error term. The dependent variable, \(\:{A}_{i}\), is observed in Eq. (2) as:

We apply the probit regression estimation technique given the binary nature of the dependent variable; the related model is stated in Eq. (3) as follows:

where \(\:\varPhi\:\) is a cumulative standard normal distribution function while all other elements of Eq. (3) maintain their usual meaning.

In the COVID-19-induced income loss models, our goal is to show the causal effect of the pandemic on farm household incomes. Due to the lack of suitable external instruments, we adopt the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) approach to shed light on the effect of being a farm household on the probability of reporting a reduction or total loss of income due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PSM approach allows us to deal with the potential endogeneity bias problem and the sample selection issueFootnote 4 in the underlying relationship by matching treated groups to their non-treated counterparts based on a set of observable baseline characteristics [33]. In this study, we include the following regressors in the estimation of the propensity scores: age and sex of the household head, educational attainment of the household head, household size, and locality (rural versus urban dummy and regional dummies). Following the precedence of earlier scholars [34, 35], we employ conventional matching methods such as Nearest-Neighbor Matching (with or without caliper and with or without replacement) to match treated households with comparable untreated counterparts, conditional on the estimated propensity scores. The suitability of the PSM approach depends, however, on the presence of common support between treated and non-treated households. Figure 4 (in the Appendix) illustrates the extent to which the treated households are matched with their untreated counterparts based on the propensity scores. The summary statistics of the main independent variables in COVID-induced income reduction models are presented in Table 6 in the Appendix.

5 Results and discussion

In this section, we present the main results of the study concerning our two research questions. First, we present the results of our estimation of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of farm versus non-farm households; and finally, we discuss the coping (mitigating or diversification) strategies adopted by farm households during the pandemic.

5.1 What was the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of farm versus non-farm households?

Figure 2 plots responses to the question of whether individuals witnessed a change in their incomes relative to the month preceding the month of the survey round. Uganda imposed a COVID-19-related lockdown and school closures on 20 March 2020. In the month following the imposition of the lockdown, over 55% of households reported a reduction in income compared with the pre-COVID level, while more than a quarter of households reported experiencing a total loss in income or earnings. Only 1.6% of households reported an increase in their income during the month immediately after the lockdown and school closures were introduced. Similarly, Andrieu et al. [24], narrated in their study that the imposition of lockdown has resulted in a reuction in people earnings and hence decrease welfare in Burkina Faso.

Considering the differences in these responses across household types (i.e., farm versus non-farm, Panel B), we find a marginal difference across household types in the share of households reporting either a reduction in income or a total loss. For instance, about 56% and 54% of farm and non-farm households, respectively, reported a fall in income during the immediate post-COVID lockdown period. However, there are important variations in responses to the question of whether the household’s income is above, below, or the same as the pre-COVID level (Fig. 5 in the Appendix). In particular, 58% and 45% of farm and non-farm households, respectively, reported that their current income is below its pre-COVID level. Bouët et al. [29] also indicated that the COVID-19 has eroded most people’s income including loss of jobs in Africa.

Although these descriptive primary data provide insight into the differential effects of the pandemic on the welfare of farm versus non-farm households, they nevertheless fall short of providing rigorous evidence of an underlying relationship. Consequently, we estimate the effect of being a farm household on the probability of reporting a reduction or total loss of income after the imposition of COVID-19-related restrictions and see that farm households are about 3.2% more likely to report a reduction/loss in income during the COVID period relative to their non-farm counterparts (Table 2).

Among farm households, however, there are differences across our different covariates. For example, households headed by males have a lower probability of reporting a reduction/loss in income during the COVID period than female-headed households, while households in the Western region are 5–10% less likely to report a reduction/loss in income during the COVID period. These results are, however, not entirely consistent when we disaggregate the sample across rounds of the surveys (see Tables 4 and 5 in the Appendix) but are broadly maintained when we use a potential endogeneity bias-corrected estimation strategy: that is, the PSM approach (Table 3). Osabuohien et al., [9] asserted that the effect of the COVID-19 had different degrees on different people considering where they found themselves (either urban or rural dwellers) and the gender of the individuals.

The findings from the survey round-disaggregated analysis indicate that in the month immediately following the imposition of pandemic-related restrictions in Uganda, farm households were not disproportionately affected by those restrictions compared with non-farm households. This story, however, changed over time, with farm households witnessing significant reductions in income during the post-pandemic period compared with non-farm households.

5.1 What mitigating measures or diversification strategies were adopted by farm households amid the crisis?

In Fig. 3, we show that, unlike non-farm households, farm households adopted a wide range of measures to mitigate the effects of shocks on their welfare. The most common coping strategies adopted by households amid the COVID-19 crisis were reliance on savings, receiving assistance from friends, and reducing food consumption. However, around a third of farm households responded to the crisis by doing nothing. Among farm households, reliance on savings, engaging in additional income-generating activities, receiving assistance from friends, and reducing food consumption were the top five risk-coping strategies.

6 Conclusion

Agricultural activities in many African countries are affected by a range of risk factors. Exposure to or experience of such risks may vary across farmers and localities as well as contexts. This issue has, however, received limited attention in the literature. Therefore, this study examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions on the welfare of farm households. Using micro-data – namely, High-Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) on COVID-19 datasets for Uganda—we observe that the probability of experiencing risks related to agriculture is significantly influenced by a range of individual- and farm-level/contextual factors, these effects show considerable variations across contexts.

In addition, we show that farm households witnessed significant income reductions during the COVID-19 period in Uganda. In terms of the coping strategies households adopt amid the crisis, we find that, unlike non-farm households, farm households adopt a range of risk-coping mechanisms, including reliance on savings, engaging in additional income-generating activities, receiving assistance from friends, and reducing food consumption. These findings point towards the need to incorporate individual-level and farm-level/contextual factors into approaches aimed at reducing farmers’ vulnerability to agricultural risks, thereby contributing to improvements in on-farm productivity and farmer welfare.

The caveat in this study is that we are not trying to establish a causal effect but give an inference showing the relationship among the key variables in the study. The results of the study is based on Ugandan data; hence, generalisation to other countries may not be easily feasible, which could be taken up in further research. Also, we used cross-sectional datasets that are usually collected at a point in time, which does not cover understanding of changes in the variables of interest over time. Thus, follow-up studies, can focus on panel data to cover time-dimension of the discourse.

Data availability

The data to this study is publicly available at the website of the World Bank.

Code availability

The estimation codes for this research are available upon request.

Notes

See Hoddinott and Quisumbing (2003) for a detailed discussion on how risks/shocks can affect household welfare.

Round 1 June 2020; Round 2 July/August 2020; Round 3 September/October (1st–2nd ) 2020; Round 4 October (27th–31st )/November 2020; Round 5 February 2021; Round 6 March/April 2021; Round 7 October/November 2021.

Given our interest in demonstrating whether farm households are hurt more than their non-farm counterparts by the COVID-19 pandemic, this variable is included only in the COVID-19-induced income loss models.

This issue arises because households decide whether to participate in farm activities or not, and this decision may be influenced by observable and/or unobservable factors that are peculiar to these households.

References

World Bank. World development indicators (WDI) database. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2022.

Osabuohien E, editor. The Palgrave handbook of agricultural and rural development in Africa. Basingstoke. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41513-6

Ruml A, Chrisendo D, Iddrisu AM, Karakara AA, Nuryartono N, Osabuohlen E, Lay J. Smallholders in agro-industrial production: lessons for rural development from a comparative analysis of Ghana’s and Indonesia’s oil palm sectors. Land Use Policy. 2022;119:106196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106196.

Edafe O, Osabuohien E, Matthew O, Osabohien R, Khatoon R. Large-scale agricultural investment and female employment in African communities: quantitative and qualitative Insights from Nigeria. Land Use Policy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106579.

Karakara AA, Nunoo J, Coffie M. Gender, forms of land ownership and agriculture value chain participation: empirical insights from smallholder farmers in Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria. Afr J Land Policy Geospat Sci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.48346/IMIST.PRSM/ajlp-gs.v7i3.46182.

PARM (Platform for Agricultural Risk Management). Agricultural risk management: practices and lessons learned for development. Platform for Agricultural Risk Management: Rome; 2017.

Ahsan DA. Farmers’ motivations risk perceptions, and risk management strategies in a developing economy: Bangladesh experience. J Risk Resour. 2011;14:325–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.541558.

Bergfjord OJ. Farming and risk attitude. Emirates J Food Agric. 2013;25:555–61. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.v25i7.13584.

Osabuohien E, Odularu G, Ufua D, Osabohien R. COVID-19 in the African continent: sustainable development and socioeconomic shocks. Emerald Publishers Limited: Bingley. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80117-686-620221002.

Adediran O, Osabuohien E, Silberberger M, Osabohien R, Adebayo G. Agricultural value chain and households’ livelihood in Africa: the case of Nigeria. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e28655.

Gralak S, Spajic L, Blom I, Omrani OE, Bredhauer J, Uakkas S, Mattijsen J, et al. COVID-19 and the future of food systems at the UNFCCC. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(8):309–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30163-7.

World Health Organisation. Pandemic influenza puts additional pressure on sub-Saharan Africa’s health systems. https://www.afro.who.int/news/pandemic-influenza-puts-additional-pressure-sub-saharan-africas-health-systems. Accessed 26 Sep 2022.

Nhemachena C, Murwisi K. A rapid analysis of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on selected food value chains in Africa. Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA): Nairobi; 2020.

Ufua D, Osabuohien E, Ogbari M, Falola H, Okoh E, Lakhani A. Re-strategising government palliative supportsystems in tackling the challenges of COVID-19 lockdown in Lagos state, Nigeria. Glob J Flex Syst Manag. 2021;22:19–32.

Nassary EK, Baijukya F, Ndakidemi PA. Assessing the productivity of common bean in intercrop with maize across agro-ecological zones of smallholder farms in northern highlands of Tanzania. Agriculture. 2020;10(117):1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10040117.

Rural21. COVID-19 threatening efforts to reduce rural poverty. 2020. https://www.rural21.com/english/news/detail/article/covid-19-threatening-efforts-to-reduce-rural-poverty.html. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

Ojiewo CO, Pillandi R. Africa is facing a food crisis due to COVID-19. These seeds could help prevent it. World Economic Forum. 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/africa-food-crisis-covid-19-seed-revolution/. Accessed 26 Sep 2022.

Brahmbhatt M, Dutta A. On SARS type economic effects during infectious disease outbreaks. Policy research working paper The World Bank: Washington, D.C. 2008; 4466. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4466

CCAFS (CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security). 2020. How we can use the covid-19 disruption to improve food systems and address the climate emergency. https://www.cgiar.org/news-events/news/how-we-can-use-the-covid-19-disruption-to-improve-food-systems-and-address-the-climate-emergency/. Accessed 3 April 2024.

Amjath-Babu TS, Krupnik TJ, Thilsted SH, McDonald AJ. Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Secur. 2020;12(4):761–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2.

Devereux S, Béné C, Hoddinott J. Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Secur. 2020;12:769–70.

Hammond J, Siegal K, Milner D, Elimu E, Vail T, Cathala P, Gatera A, et al. Perceived effects of COVID-19 restrictions on smallholder farmers: evidence from seven lower- and middle-income countries. Agric Syst. 2022;198:103367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103367.

Siche R. What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture? Sci Agropecu. 2020;11(1):3–6. https://doi.org/10.17268/sci.agropecu.2020.01.00.

Andrieu N, Hossard L, Graveline N, Dugue P, Guerra P, Chirinda N. COVID-19 management by farmers and policymakers in Burkina Faso, Colombia and France: lessons for climate action. Agric Syst. 2021;190:103092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103092.

Amankwah A, Gourley S. Impact of COVID-19 crisis on agriculture: evidence from five sub-Saharan African countries. World Bank living standards measurement study. World Bank: Washington, DC; 2021.

Goswami R, Roy K, Dutta S, Ray K, Sarkar S, Brahmachari K, Nanda M. Multi-faceted impact and outcome of COVID-19 on smallholder agricultural systems: integrating qualitative research and fuzzy cognitive mapping to explore resilient strategies. Agric Syst. 2021;189:103051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103051.

Medinilla A, Byiers B, Apiko P. 2020. African regional responses to COVID-19. ECDPM discussion paper. European Centre for Development Policy Management: Maastricht; 272.

Bao NG, Bouët A, Traoré F. On the proper computation of ad valorem equivalent of non-tariff measures. Appl Econ Lett. 2020;29(4):298–302.

Bouët A, Laborde D, Seck A. The impact of COVID-19 on agricultural trade, economic activity and poverty in Africa. Afr Agric Trade Monitor 2021 Rep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.54067/9781737916406.

Kyeyune H. Shutdown in Uganda over COVID-19 hits poor hard. Anadolu agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/shutdown-in-uganda-over-covid-19-hits-poor-hard/1787526. Accessed 26 Sep 2022.

UN Migration Agency. 2020. Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) COVID-19 regional overview on mobility restrictions. https://migration.iom.int/sites/default/files/public/reports/ IOM_DTM_RDH_COVID-19_Mobility_Restrictions_16072020.pdf. Accessed 5 Oct 2022.

Natukunda A. 28 year-old agribusiness owner in uganda uses radio delivery to adapt to COVID-19. Palladium. https://thepalladiumgroup.com/news/28-Year-Old-Agribusiness-Owner-in-Uganda-Uses-Radio-Deliveries-to-Adapt-to-COVID-19. Accessed 6 Oct 2022.

Iddrisu AM, Danquah M. 2021. The welfare effects of financial inclusion in Ghana: an exploration based on a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. WIDER working paper2021/146. UNU-WIDER: Helsinki. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2021/086-3

Zhang Q, Posso A. Thinking inside the box: a closer look at financial inclusion and household income. J Dev Stud. 2019;55(7):1616–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1380798.

Daudu AK, Karakara AA-W, Kareem OW, Olatinwo LK, Dolapo TA, Egbewole HO, Adefalu LL, Abdulwahab SA. Does farm wage influence gender gap in household welfare? A microlevel evidence from Nigeria. Preprints. 2024. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202406.1412.v1.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws from the study commissioned under the UNU-WIDER project SOUTHMOD - simulating tax and benefit policies for development Phase 2, which is part of the Domestic Revenue Mobilisation programme. The initial research report was featured as WIDER Working Paper 117/2022 (DOI: https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2022/251-5 ). A version of the paper was also presented at AGRODEP 2023 Conference in Kigali, Rwanda. The views expressed are those of the authors.

Funding

This paper draws from the study commissioned under the UNU-WIDER project SOUTHMOD - simulating tax and benefit policies for development Phase 2, which is part of the Domestic Revenue Mobilisation programme which was funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.I and A.A.K. conceptualized the study and wrote the main manuscript text and E.O. provided supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors whose names appear on the submission made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors followed the required ethics in preparing this manuscript. We used secondary data which doesn’t require ethics approval for data collection.

Consent for publication

This study used secondary data and thus, the authors did not collect the data directly of which informed consent to participate is applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 4,5, 6 and Figs. 4, 5.

Post-COVID income change (% share of households); income concept 2. A Full sample. B Farm vs. non-farm households. Responses are in answer to the question: ‘Since March 20, 2020, the day that schools were closed, has income from the activity increased, stayed the same, reduced, or become a total loss (no earnings)?. The authors’

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osabuohien, E.S., Karakara, A.AW. & Iddrisu, A.M. COVID-19 pandemic, household welfare and diversification strategies of smallholder farmers in Uganda. Discov Sustain 5, 303 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00507-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00507-9