Abstract

Vaccines against COVID-19 and influenza can reduce the adverse outcomes caused by infections during pregnancy, but vaccine uptake among pregnant women has been suboptimal. We examined the COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake and disparities in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic to inform vaccination interventions. We used data from the Oxford-Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre database in England and the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Databank in Wales. The uptake of at least one dose of vaccine was 40.2% for COVID-19 and 41.8% for influenza among eligible pregnant women. We observed disparities in COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake, with socioeconomically deprived and ethnic minority groups showing lower vaccination rates. The suboptimal uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines, especially in those from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds and Black, mixed or other ethnic groups, underscores the necessity for interventions to reduce vaccine hesitancy and enhance acceptance in pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infections with COVID-19 and influenza during pregnancy can increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes1,2 as pregnancy weakens the immune system3. Vaccinations against COVID-194 and influenza5 were found to reduce these adverse outcomes and are therefore included in the routine immunisation schedule for pregnant women in the United Kingdom (UK)6. However, although COVID-19 and influenza vaccines are recommended for pregnant women, their uptake during pregnancy remains suboptimal7,8. This may be due to concerns about side effects and vaccine safety among pregnant women9, also known as vaccine hesitancy, which were found to be related to their demographics and baseline health conditions7,10,11,12.

Previous studies suggested the uptake of COVID-19 or influenza vaccines among pregnant women was lower in younger age groups7,10, black or unknown ethnicity10,11, deprived socioeconomic status10,11, those with no known risk factors for influenza11,13 and those living in large multigenerational household composition12. None of the available studies provided a population-level evaluation of COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake in pregnant women in England and Wales, particularly regarding how disparities in baseline characteristics impact uptake. Understanding vaccine uptake disparities in pregnant women would inform clinicians and policymakers in developing strategies to promote vaccination and reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes in the UK.

The uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic could differ from normal times because of changes in vaccine hesitancy levels during a pandemic14 and the introduction and rollout of the new COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy may be more prevalent for COVID-19 vaccines due to limited evidence on maternal and neonatal safety available at the time of rollout15,16. The COVID-19 vaccination programme in the UK was initially rolled out centrally and followed a three-phase approach17,18, which may have had a significant impact on the timing of vaccination among pregnant women. Phase 1 of the rollout started on 8 December 2020, aiming to vaccinate the priority groups (health and care workers, those aged over 50, those considered clinically extremely vulnerable, and those aged over 16 with underlying health conditions) with two doses18. Phase 2 began in April 2021 and aimed to vaccinate people aged 18-49 with two doses18. Phase 3 included vaccinations for those aged 12 and over, as well as the rollout of booster vaccines starting in September 202118. Influenza vaccination, on the other hand, was traditionally run through general practice in winter seasons, though pharmacies are also widely involved19.

We carried out this study to examine the COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake and disparities in pregnant women in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic between September 2020 and March 2022. We described the characteristics of pregnant women eligible for COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in England and Wales. We assessed the uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in pregnant women during the pandemic. We investigated the COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake disparities in pregnant women by identifying associations between baseline characteristics (i.e., age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, rurality, household size, obesity and the number of comorbidities) and receiving a vaccine.

Results

Cohort selection and baseline characteristics

A total of 133,300 pregnant women were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination during their pregnancy across England and Wales. We identified 178,690 pregnant women eligible for 2020/21 or 2021/22 seasonal influenza vaccination across England and Wales. There were 133,140 pregnant women in the study cohorts who were eligible for both COVID-19 and influenza vaccinations during pregnancy. The distribution of baseline characteristics was consistent between COVID-19 and influenza cohorts (Table 1).

Vaccine uptake in pregnant women

Of the 178,690 pregnant women in the influenza cohort, 74,740 (41.8%) received at least one dose of influenza vaccine (Table 1). Of the 133,300 individuals in the COVID-19 cohort, 53,550 (40.2%) received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine from any vaccination setting. Among the 133,140 pregnant women eligible for both vaccinations, 57,970 (43.6%) did not receive either vaccine, 27,350 (20.5%) received both vaccines, 26,190 (19.7%) only received the COVID-19 vaccine and 21,630 (16.2%) only received influenza vaccine (Fig. 1).

Influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women had a seasonal pattern and was highest between September and December in each season. The 2020/21 season saw a higher peak in the weekly number of influenza vaccinations than the 2021/22 season. The uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in pregnant women was in line with the COVID-19 vaccination programme, with Phase 2 immunisation beginning in April 2021 (Fig. 2).

a The weekly uptake of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women across England and Wales between September 2020 and March 2022, categorised by Dose 1, Dose 2 and Dose3. b The weekly uptake of influenza vaccination in pregnant women across England and Wales, categorised by the 2020/21 and 2021/22 influenza seasons.

Factors associated with vaccine uptake

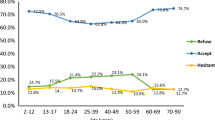

The COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake exhibited similar disparities across ethnic groups, deprivation quintile (i.e., socioeconomic status), household size, and rurality (Fig. 3). Pregnant women in the black ethnic group had the least chance of receiving either vaccine (COVID-19 aOR: 0.48, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.45–0.51; Influenza aOR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.57–0.65), while those of mixed (COVID-19 aOR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.74–0.87; influenza aOR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.79–0.91) and other (COVID-19 aOR: 0.69, 95%CI 0.63–0.76; influenza aOR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.74–0.86) ethnic groups had a slightly higher chance of receiving vaccines, but still lower than those of white (reference group) or Asian ethnic group (COVID-19 aOR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.97–1.06; influenza aOR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.04–1.12).

There was a strong gradient of reduced vaccine uptake with the increase in deprivation. Pregnant women from the most deprived area had a much lower chance of receiving either vaccine (COVID-19 aOR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.43–0.46; influenza aOR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.56–0.60), compared to those from the least deprived areas. In comparison to households of two, vaccine uptake was lower in all the other household sizes. Additionally, those living in rural areas had a higher chance of receiving both vaccines than those living in urban areas (COVID-19 aOR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.10–1.17; influenza aOR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08–1.14).

The vaccine uptake was inconsistent across age, comorbidity, and BMI groups between the two vaccines. Compared to the 25–29 age group, pregnant women aged 40–49 had the highest chance of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine (aOR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.94–2.15), but the lowest chance of receiving the influenza vaccine (aOR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.69–0.76). Meanwhile, pregnant women aged 18–24 had a low chance of receiving both vaccines (COVID-19 aOR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.74–0.79; influenza aOR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.75–0.80). Compared to pregnant women with no comorbidities, those with comorbidities had a higher chance of receiving the influenza vaccine. However, this trend was not observed for COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant women with one to two comorbidities. In comparison to pregnant women with normal BMI, pregnant women with a BMI over 40 (severely obese) had a higher chance of receiving influenza vaccine (aOR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.10–1.23), while there was no difference in receiving COVID-19 vaccine (aOR: 1.00, 95%CI: 0.94–1.07). Pregnant women with a BMI under 18.5 had the lowest chance of receiving both vaccines (COVID-19 aOR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.78–0.88, Influenza aOR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.78–0.86).

Discussion

Our analysis across England and Wales presented a low COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic, with COVID-19 vaccine uptake higher in 2021/22 and influenza vaccine uptake higher in the 2020/21 season. We identified vaccine uptake disparities across various baseline characteristics, particularly among different ethnic groups and socioeconomic statuses. Women of lower socioeconomic status had a significantly lower chance of receiving COVID-19 or influenza vaccination. Women in black, mixed, and other ethnic groups had a lower chance of being vaccinated in comparison to women in white or Asian ethnic groups.

The vaccine uptake in our study aligns with existing data. UKHSA estimated influenza vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women in England as 43.6% in 2020/21 and 37.9% in 2021/2220, which matches our observed rate of 41.8%. UKHSA reported that 32.3% of women who gave birth in England in September 2021 and 53.7% of women who gave birth in December 2021 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine21,22, aligning with our finding of 40.1%. The reports from UKHSA also support our observation that COVID-19 vaccine uptake was higher in the 2021/22 season, while influenza vaccine uptake was higher in the 2020/21 season among pregnant women.

Our study revealed disparities in COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women across various baseline characteristics during the COVID-19 pandemic. The determinants of accepting COVID-19 or influenza vaccines identified in our study include being socioeconomically affluent, of white or Asian ethnicity, living in rural areas, and residing in two-person households. These determinants align with findings from studies conducted in other countries, during non-pandemic periods, as well as from smaller-scale or qualitative studies11,12,23,24,25,26. We found that pregnant women aged 40–49 had a higher chance of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine but a lower chance of receiving the influenza vaccine. This finding was also noted in previous studies, where older age was identified as a predictor of receiving COVID-19 vaccines7,27,28 while being over 40 was linked to lower influenza vaccine uptake11,24.

The rollout strategy of the COVID-19 vaccine played an important role in vaccine uptake among pregnant women. The expansion of the influenza vaccination programme in the UK in 2020 aimed to safeguard vulnerable individuals from influenza, given the simultaneous circulation of COVID-19 and influenza viruses29. This initiative was important due to the limited availability of COVID-19 vaccines at the time29. The higher uptake of the influenza vaccine during the 2020/21 season, as found in our study, reflects the effect of the expanded influenza vaccination programme. Conversely, the increased uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine during the 2021/22 season reflects a more sufficient supply of COVID-19 vaccine. The difference in COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake among the 40–49 age group may also be relevant to the age-based rollout strategy for COVID-19 during the pandemic, as well as the heightened concerns associated with the novelty of the COVID-19 virus compared to influenza30.

Our study suggested that pregnant women with one or two comorbidities had a lower chance of accepting the COVID-19 vaccine compared to those with no comorbidities, which is opposite to the uptake pattern for the influenza vaccine. Influenza vaccine has been recommended for people in clinical risk groups (e.g. chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease and vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, etc.) in the UK since the 1960s31,32. The concept that the influenza vaccine can protect people with comorbidities from the risk of developing serious illness if they contract influenza has been well accepted in the general population32,33. Therefore, we observed pregnant women with one or two comorbidities had a higher chance of receiving influenza vaccine than those without comorbidities. In contrast, the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in people with comorbidities was not fully studied at the time of the vaccination programme rollout34, which may increase vaccine hesitancy among patients with comorbidities33. The wide 95% confidence intervals shown for pregnant women with three or four comorbidities in the logistic regression results were mainly due to the small sample size in these two categories.

We found that the uptake for both COVID-19 and influenza vaccines was suboptimal in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among those in socioeconomically deprived groups and in black, mixed, and other ethnic groups. The mechanisms for lower vaccine uptake in people with more deprived socioeconomic status could include access to transport, confidence in vaccination, vaccination knowledge, and trust in healthcare or vaccination providers, according to an umbrella review35. A potential reason contributing to low vaccine uptake in ethnic minority groups could be a language barrier36. Another reason could be the over-registration in the UK primary care system. Over-registration is more people registered with a general practice than the estimated residents in the country. The over-registration rate in primary care in England was estimated to be 3.9% (n = 2,097,101) in 2014 and was found to be associated with non-White British residents and higher levels of social deprivation37. Pregnant women registered with a GP but not living in the UK are less likely to respond to the vaccine invitation, especially immigrants who choose to give birth in their home country. This issue can result in a falsely lower vaccine uptake among non-white ethnicities.

A strength of our study is that we used large national representative primary care data in England38 and Wales39. The longitudinal data provided insights into the trend of vaccination over seasons. Another strength is that we examined the vaccine uptake for both COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in the same population during the same time period. This study design facilitated a comparison between the vaccine uptake disparities for the two vaccines. Also, we adjusted the logistic regression model for multiple factors that may influence vaccine uptake decisions to minimise the risk of confounding and make the observed disparities in ethnicity and SES status more reliable.

There are limitations in this study. The influenza vaccine uptake information only accounted for vaccines recorded in the GP medical records and may underestimate the uptake rate. This is because vaccinations took place in pharmacies and other community or hospital settings, and vaccinations administered in other countries may not be recorded in the GP medical records. This may lead to bias in the results if certain groups of patients tend to receive the vaccine outside of general practices. Pregnancy in this study was identified from primary care medical records and may have delays in the recording of labour and miscarriages, which could cause misclassification of pregnant time periods. Also, the start date of pregnancy was derived using an algorithm based on the information available in the medical records, which may not be entirely accurate. The inclusion of non-term pregnancies in the study cohorts may introduce bias, as previous research has shown low COVID-19 vaccine uptake during the last trimester in Scotland25 and low influenza vaccine uptake during the first trimester in the UK40. Although our study adjusted for many factors, some factors, such as smoking status, educational background and changes in recommendations on COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women, as well as other unmeasured confounding factors, were not accounted for in the analysis. Also, the granularity of ethnicity in our study was relatively broad, which may neglect the difference between ethnic minorities. For example, we grouped Bangladeshi/Pakistani people with Chinese people in the Asian ethnicity group, but the vaccine uptake hesitancy is much higher in Bangladeshi/Pakistani than in Chinese people41.

Our study emphasised the suboptimal uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines among pregnant women, even during the COVID-19 pandemic when awareness of the importance of vaccination was heightened. Common reasons for vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women include fear of side effects or adverse events, lack of confidence in vaccine safety and low perceived risk of infection during pregnancy9. Although the safety of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in pregnant women has been well proven in clinical studies28,42, it does not seem to be well perceived by the public. Pregnant women with one or two comorbidities showed particular concern about receiving COVID-19 vaccines. This concern could likely be alleviated by providing them with the most up-to-date evidence on COVID-19 vaccine safety.

Evidence shows that receiving a direct recommendation from healthcare providers, either through a consultation or a written message, can significantly increase influenza vaccine uptake in pregnant women8,43. Mitchell et al.9 constructed a framework that divided pregnant women into four distinctive groups according to their stage of vaccine hesitancy and recommended dedicated communication routes for each group9. Healthcare providers may use this framework to optimise their communication strategy, while more efforts should be put into ethnic minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged pregnant women. Frequent updates on new evidence regarding vaccine safety to healthcare providers and pregnant women are also recommended44.

In addition to the direct communication provided by healthcare providers, public agencies may routinely assess the efficacy and inequalities in vaccination delivery and implement policies to reduce such inequalities17. Our findings regarding vaccine uptake disparities are also informative for policy-making in vaccination programmes, particularly as vaccination against respiratory syncytial virus is under consideration for pregnant women by the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation45. On the research front, improved recording of vaccination information in electronic health records would be beneficial for future studies.

This study highlights the suboptimal uptake of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in those from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds and black, mixed or other ethnic groups. The COVID-19 phased rollout strategy had a strong impact on the COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake pattern in pregnant women during the pandemic. Disparities in COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women underscore the necessity for interventions from the perspectives of healthcare providers, public agencies, and scientists to reduce vaccine hesitancy and improve acceptance in pregnant women. Future studies may explore the reasons for vaccine uptake disparities identified in this study and investigate the relationship between receiving the COVID-19 vaccine and the influenza vaccine in pregnant women.

Methods

Data source

We used individual-level routinely collected primary care data and linked vaccine immunisation data from two separate large databases in England and Wales. For England, we used the nationally representative Oxford-Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Research and Surveillance Centre (RSC) database, which covered around 32% of the English population (N > 19 million people) registered with over 1900 general practices across England38. The pseudonymised primary care data is linked to the National Immunisation Management Service for vaccination data. For Wales, we used the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank trusted research environment (TRE), which covered 3·2 million people from 329 (84%) general practices across Wales39, linked to national COVID-19 vaccination data in Welsh Immunisation System46. Both the RCGP RSC database38 and the SAIL databank39 are primary care databases that are representative of both demographic and clinical aspects compared to the national population.

Primary care data provide pseudonymised information on patients’ demographics, disease diagnoses and some vaccinations recorded in general practices. Primary care services are the first point of contact in the UK healthcare system47, so primary care data linked with external vaccination databases would provide the complete patient demographics, medical and vaccination information needed for this study.

In England, ethical approval was granted by the Health Research Authority London Central Research Ethics Committee (reference number REC reference 21/HRA/2786; integrated research application system number 30174). In Wales, research conducted within the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage Databank was done with the permission and approval of the independent Information Governance Review Panel (project number 0911). Individual written patient consent was not required for this study.

Cohort selection

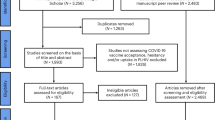

The two national cohorts included women aged 18 to 49 who were eligible for either COVID-19 vaccination, influenza vaccination or both during the course of pregnancy between September 2020 and March 2022 in England and Wales (Fig. 4).

a The inclusion period for this study starts in September 2020 and ends in March 2022. b The inclusion period for the influenza vaccine was divided into two seasons: the 2020/21 season, which covered 1 September 2020–31 March 2021, and the 2021/22 season, which covered 1 September 2021–31 March 2022. The inclusion period for the COVID-19 vaccine started on 8 December 2020 and ended on 31 March 2022.

In the UK, pregnant women have been eligible for free influenza vaccination in the influenza season since 2010 48. For the present study, we analysed influenza vaccinations during the 2020/21 and 2021/22 seasons. Eligibility for the COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women changed over time. Pregnant women were first offered the COVID-19 vaccine in December 2020 (Phase 1 rollout) if they were health and social care workers or in an at-risk group49. They were then eligible based on age groups from April 2021 (Phase 2 rollout) and were added to the clinical risk groups for COVID-19 vaccination in December 202149. Thus, analysis for COVID-19 and influenza vaccines was performed on two separate cohorts to account for differences in these vaccination programmes (Fig. 4).

The influenza cohort included pregnant women who were pregnant for at least 30 days during the seasonal influenza immunisation programme rollout period in either the 2020/21 season (1 September 2020–31 March 2021) or the 2021/22 season (1 September 2021–31 March 2022).

The COVID-19 cohort comprised women who were pregnant for at least 30 days after they were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccination, whether first or any subsequent dose between 8 December 2020 and 31 March 2022. This means the women must have either been unvaccinated 30 days into their pregnancy and become eligible at least 30 days before the end of pregnancy or if they have already had a vaccination (dose 1 or 2) before 30 days into pregnancy, they must have become eligible for a second or third dose (over 8 weeks after the previous dose) at latest 30 days before the end of pregnancy.

The start date of a pregnancy was defined as the first day of the last menstrual period. The end date of pregnancy was defined as the date of the delivery of the foetus or the termination of the pregnancy, such as miscarriage. Both dates were identified from the primary care medical records using a developed algorithm50,51. For pregnant women who had more than one pregnancy during the study period, we included only their first pregnancy for analysis.

Outcome measure

Our primary outcomes were the uptake of the COVID-19 and the influenza vaccine during pregnancy between September 2020 and March 2022. The vaccine uptake was defined as the number of pregnant women in the cohort who received at least one vaccination during the study period, divided by the total number of pregnant women in the cohort, and presented as a percentage.

Baseline characteristics were measured as predicting factors (i.e. independent variable) for vaccination. We measured age (categorised as 18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 and 40–49), ethnic groups (categorised as white, Asian, black, mixed, others and unknown), body mass index (BMI, categorised as <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–39.9, 40.0 or more and unknown), number of comorbidities (categorised as none, 1, 2, 3 and 4 or more), household size (categorised as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6–10 and 11 or more), socioeconomic status of the residential area (categorised as 1—most deprived, 2, 3, 4 and 5—least deprived) as well as rurality. Additionally, the residing health board for Wales (e.g. Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, etc.) and regions for England (e.g. London, the North West, North East, Yorkshire, East Midlands, etc.) were included to control for potential confounding effects caused by differences in the distribution of the population as well as delivery of the vaccination programmes within each country.

Data for these factors are available from the primary care databases RCGP and SAIL Databank. Demographics (i.e. age, ethnicity, BMI, household size and socioeconomic status) were identified at the study start date. The traceback period for identifying comorbidities was five years. Socioeconomic status was based on the quintiles of the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) in England and52 the 2019 Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) in Wales53 and was derived using patients’ Lower-layer Super Output Area (LSOA) of residence. Since BMI and ethnic groups were not available for all the individuals, we included an unknown category to represent this. Household size was determined by the number of family members registered at the same GP practice as the pregnant women.

The comorbidities in this study were defined in line with the clinical risk groups for the COVID-19 immunisation programme as stated in Chapter 14a in Immunisation Against Infectious Disease (The Green Book)49, the UK immunisation guidance. The comorbidities included are chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological disease, diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression. For England, these comorbidities were identified as part of the PRIMIS v2.3 specification54, a national data specification commissioned by the UK Health Security Agent (UKHSA) to help identify priority patients for the COVID-19 vaccination. For Wales, the comorbidities were derived from QCOVID indicators55 that were part of a COVID-19 risk prediction model.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive analysis to present the baseline demographics and comorbidities of the two cohorts (i.e. the COVID-19 cohort and the influenza cohort). We presented the weekly number of vaccinations received by individuals in each cohort over the study period in bar charts. We also presented the vaccine uptake in the sub-cohort of women eligible for both vaccines during their pregnancy, which included uptake of influenza vaccine only, uptake of COVID-19 vaccine only, uptake of both vaccines and uptake of neither vaccine.

We conducted a multivariable fixed-effect logistic regression analysis to explore factors associated with vaccine uptake among pregnant women. The regression estimates adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for the covariates, which were reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Descriptive statistics (frequencies) were summed, and the cohort-specific log odds ratios were meta-analysed to produce summary odd ratios. A fixed effect model was used as the same effects were anticipated in each country and as we are only using meta-analysis methods to replicate a pooled analysis. All analytical work was done using R version 4.1.356.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Oxford-Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Research and Surveillance Centre (RSC) database and the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank trusted research environment (TRE) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of RCGP RSC and SAIL TRE.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis and processing in this manuscript is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Wang, H. et al. The association between pregnancy and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 56, 188–195 (2022).

Mertz, D. et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe outcomes from influenza virus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Vaccine 35, 521–528 (2017).

PrabhuDas, M. et al. Immune regulation, maternal infection, vaccination, and pregnancy outcome. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 30, 199–206 (2021).

Kalafat, E. et al. Benefits and potential harms of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: evidence summary for patient counseling. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 57, 681–686 (2021).

Jamieson, D. J. et al. Benefits of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 207, S17–S20 (2012).

UK Health Security Agency. Complete Routine Immunisation Schedule from 1 September 2023 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 21 May 2024); https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-complete-routine-immunisation-schedule/the-complete-routine-immunisation-schedule-from-february-2022.

Galanis, P. et al. Uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050766 (2022).

Wiley, K. E. et al. Uptake of influenza vaccine by pregnant women: a cross-sectional survey. Med. J. Aust. 198, 373–375 (2013).

Mitchell, S. L., Schulkin, J. & Power, M. L. Vaccine hesitancy in pregnant Women: a narrative review. Vaccine 41, 4220–4227 (2023).

Blakeway, H. et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, 236.e1–36.e14 (2022).

Woodcock, T. et al. Characteristics associated with influenza vaccination uptake in pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 73, e148–e155 (2023).

Lench, A. et al. Household composition and inequalities in COVID-19 vaccination in Wales, UK. Vaccines (Basel) 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030604 (2023).

Wierzchowska-Opoka, M. et al. Impact of obesity and diabetes in pregnant women on their immunity and vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines1107124 (2023).

Bachtiger, P. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the uptake of influenza vaccine: UK-Wide Observational Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7, e26734 (2021).

Shimabukuro, T. T. et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2273–2282 (2021).

Sarantaki, A. et al. COVID-19 vaccination and related determinants of hesitancy among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10122055 (2022).

Mounier-Jack, S. et al. Covid-19 vaccine roll-out in England: a qualitative evaluation. PLoS ONE 18, e0286529 (2023).

Department of Health and Social Care. The Rollout of the COVID-19 Vaccination Programme in England. Report—Value for Money (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022).

UK Health Security Agency. Annual Flu Programme 2024 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 25 June 2024) https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/annual-flu-programme.

UK Health Security Agency. Vaccine Uptake Guidance and the Latest Coverage Data 2023 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 10 November 2023); https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/vaccine-uptake#covid-19-vaccine-monitoring-reports.

UK Health Security Agency. Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women Increasing but Inequalities Persist 2022 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 6 Dec 2023); https://www.gov.uk/government/news/vaccine-uptake-among-pregnant-women-increasing-but-inequalities-persist.

UK Health Security Agency. UKHSA Estimated that the Influenza Vaccine Uptake Rate in Pregnant Women in England was 43.6% 2022 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 31 May 2024); https://www.gov.uk/government/news/over-half-of-pregnant-women-have-now-had-one-or-more-doses-of-covid-19-vaccines#:~:text=Vaccine%20coverage%20has%20been%20increasing,to%2053.7%25%20in%20December%202021.

Callahan, A. G. et al. Racial disparities in influenza immunization during pregnancy in the United States: a narrative review of the evidence for disparities and potential interventions. Vaccine 39, 4938–4948 (2021).

Marin, E. S. et al. Determinants of influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women: demographics and medical care access. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 162, 125–132 (2023).

Stock, S. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 28, 504–512 (2022).

Okoli, G. N. et al. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence since 2000. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 100, 997–1009 (2021).

Ha, L. et al. Association between acceptance of routine pregnancy vaccinations and COVID-19 vaccine uptake in pregnant patients. J. Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2023.10.010 (2023).

Ciapponi, A. et al. Safety of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 41, 3688–3700 (2023).

Public Health England. Vaccine Update: Issue 312, October 2020 Flu Special Edition 2020 (Public Health England, accessed 3 June 2024); https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccine-update-issue-312-october-2020-flu-special-edition/vaccine-update-issue-312-october-2020-flu-special-edition.

Mhereeg, M. et al. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy: views and vaccination uptake rates in pregnancy, a mixed methods analysis from SAIL and the Born-In-Wales Birth Cohort. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 932 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07856-8 (2022).

UK Health Security Agency. Influenza: The Green Book Ch. 19 (UK Health Security Agency, 2013).

Oakley, S. et al. Influenza vaccine uptake among at-risk adults (aged 16–64 years) in the UK: a retrospective database analysis. BMC Public Health 21, 1734 (2021).

Costantino, C. & Vitale, F. Influenza vaccination in high-risk groups: a revision of existing guidelines and rationale for an evidence-based preventive strategy. J. Prev. Med Hyg. 57, E13–E18 (2016).

Antonelli Incalzi, R. et al. Are vaccines against COVID-19 tailored to the most vulnerable people?. Vaccine 39, 2325–2327 (2021).

Sacre, A. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in vaccine uptake: a global umbrella review. PLoS ONE 18, e0294688 (2023).

John, J. R., Curry, G. & Cunningham-Burley, S. Exploring ethnic minority women’s experiences of maternity care during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 11, e050666 (2021).

Burch, P., Doran, T. & Kontopantelis, E. Regional variation and predictors of over-registration in English primary care in 2014: a spatial analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 532–538 (2018).

Leston, M. et al. Representativeness, vaccination uptake, and COVID-19 clinical outcomes 2020–2021 in the UK Oxford-Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Network: Cohort Profile Summary. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e39141 (2022).

Jones, K. H. et al. A profile of the SAIL Databank on the UK Secure Research Platform. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 4, 1134 (2019).

Sammon, C. J. et al. Pandemic influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 9, 917–923 (2013).

England, N. & Improvement, N. Vaccination: Race and Religion/belief (NHS England, NHS Improvement, 2021).

Giles, M. L. et al. The safety of inactivated influenza vaccines in pregnancy for birth outcomes: a systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 15, 687–699 (2019).

Ellingson, M. K. et al. Enhancing uptake of influenza maternal vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines 18, 191–204 (2019).

Bisset, K. A. & Paterson, P. Strategies for increasing uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine 36, 2751–2759 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.013 (2018).

Department of Health & Social Care. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Immunisation Programme for Infants and Older Adults: JCVI Full Statement (Department of Health & Social Care, 2023).

Vasileiou, E. et al. Investigating the uptake, effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines: protocol for an observational study using linked UK national data. BMJ Open 12, e050062 (2022).

NHS England. Primary Care Services 2024 (NHS England, accessed 29 April 2024); https://www.england.nhs.uk/get-involved/get-involved/how/primarycare/#:~:text=Primary%20care%20services%20provide%20the,optometry%20(eye%20health)%20services.

UK Health Security Agency. Flu Vaccination Programme 2023 to 2024: Information for Healthcare Practitioners 2023 (UK Health Security Agency, accessed 30 January 2024); https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/flu-vaccination-programme-information-for-healthcare-practitioners/flu-vaccination-programme-2023-to-2024-information-for-healthcare-practitioners.

UK Health Security Agency. COVID-19: The Green Book Ch. 14a. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccination Information for Public Health Professionals (UK Health Security Agency, 2020).

Liyanage, H. et al. Ontology to identify pregnant women in electronic health records: primary care sentinel network database study. BMJ Health Care Inform. 26, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2019-100013 (2019).

Liyanage, H. et al. Near-real time monitoring of vaccine uptake of pregnant women in a primary care sentinel network: ontological case definition across heterogeneous data sources. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 264, 1855–1856, https://doi.org/10.3233/shti190682 (2019).

Ministry of Housing CLG. English Indices of Deprivation 2019 (Ministry of Housing CLG, accessed 14 August 2023); https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019.

Government W. Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 (Government W, accessed 14 August 2023); https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Community-Safety-and-Social-Inclusion/Welsh-Index-of-Multiple-Deprivation.

The University of Nottingham. About PRIMIS 2023 (The University of Nottingham, accessed 15 August 2023); https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/primis/about/index.aspx.

Hippisley-Cox, J. et al. Risk prediction of COVID-19 related death and hospital admission in adults after COVID-19 vaccination: National Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 374, 2244 (2021).

Ihaka, R. & Gentleman, R. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Data and Connectivity National Core Study, led by Health Data Research UK in partnership with the Office for National Statistics and funded by UK Research and Innovation (grant ref MC_PC_20058). This work was also supported by The Alan Turing Institute via ‘Towards Turing 2.0’ EPSRC Grant Funding. This work was supported by the Con-COV team funded by the Medical Research Council (grant number: MR/V028367/1). This work was supported by Health Data Research UK, which receives its funding from HDR UK Ltd (HDR-9006), funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), and the Wellcome Trust. Data and Connectivity: COVID-19 Vaccines Pharmacovigilance National Core Study—Uptake, safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy; children and young people; those receiving booster doses; and disease caused by different variants (2021.0158) is a partnership between the University of Edinburgh, University of Oxford, University of Strathclyde, Queen’s University Belfast, Swansea University, Imperial College London and the Office for National Statistics. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the support of BREATHE—The Health Data Research Hub for Respiratory Health (MC_PC_19004), which is funded through the UK Research and Innovation Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and delivered through Health Data Research UK. The authors would like to acknowledge all other project collaborators not involved in these analyses but contributing to wider discussions and preceding outputs. The authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data and any views or opinions presented are solely those of the author. We would like to acknowledge all the data providers who make anonymised data available for research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.de L., A.Z. and U.A. framed the idea of this study. U.A., W.M., S.B. and X.G. analysed and interpreted the patient data regarding the vaccine uptake and disparities. X.G. led the writing of the manuscript with help from U.A. S.A. was the project manager of this study. R.G. and R.B. extracted and cleaned data from RCGP RSC. W.M., S.B. and A.A. contributed to the data extraction and cleaning in SAIL Databank. U.A., X.G., W.M., S.B., M.J., GJ, U.H., J,O., C.R., R.H., A.A., A.S., S.de L. contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the study results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.S. and C.R. are members of the Scottish Government Chief Medical Officer’s COVID-19 Advisory Group. A.S. is a member of the NERVTAG Risk Stratification Subgroup and an unfunded member of AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 strategic consultancy group, the Thrombocytopenia Taskforce. C.R. is a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency COVID-19 Vaccine Benefit and Risk Working Group. S.deL has received funding through his University from Astra-Zeneca, Eli-Lilly, GSK, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Seqirus, and Takeda, and has been a member of advisory boards for Astra- Zeneca, Sanofi, and Seqirus. S.deL. is the Director of the Oxford-RCGP RSC. All other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, X., Agrawal, U., Midgley, W. et al. COVID-19 and influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in national cohorts of England and Wales. npj Vaccines 9, 147 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00934-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00934-9