Abstract

It is acknowledged that there are close relations among students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging. However, it is a dearth of exploring students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic using a large-scale data with comparative perspectives. Thus, this study used Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 and 2022 data to explore the factors that influenced students’ subjective well-being (SWB) in six countries and regions (the United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China) and examine changes in these factors from 2018 to 2022. 153,052 students were assessed in 2018 and 2022, of which 78,257 were assessed in 2018 and 74,795 were assessed in 2022. The results showed that students’ SWB was significantly lower in 2022 than in 2018. Individual factors had the greatest influence on students’ SWB, and this influence increased from 2018 to 2022. The influence of family factors also increased during this period, whereas the influence of school factors decreased. The factor that was most closely related to SWB changed from parent-child relationships (2018) to students’ health level (2022), which significantly predicted students’ SWB. School bullying had a significant negative impact on students’ SWB, and the need to repeat the grade had a weak negative impact on SWB. In addition, school belonging played a mediating role in the relationship between bullying and students’ SWB, and the influence of students’ family economic status on their SWB was moderated by students’ peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships. This study also contributes to timely and effective educational and psychological interventions and implications for students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging under similar public health emergencies globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Students’ well-being/happiness is a focus of school education worldwide (Lucas-Molina et al., (2018); Soutter et al., (2014)). Adolescence is a key transitional stage for physical and emotional development. Establishing good psychological coping mechanisms, a positive and healthy emotional state, and decision-making abilities during this period can lay a foundation for developing self-awareness, which helps to form a positive and healthy mental state and supports comprehensive physical and mental development (Casas 2011). In middle school, students are still developing their personality characteristics and cognitive level, and their physical and mental state is therefore susceptible to the impact of major public health events such as the novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) pandemic (Rodriguez et al. 2020). For example, loneliness due to separation from relatives and peers, difficulties in adapting to new teaching methods, uneven quality of online education, and social distance limitations due to closed management, etc. All these influences from individuals, schools and families are likely to negatively affect students’ physical and mental health and well-being. The large amount of data collected by PISA can help to analyze the performance and changes of students’ well-being and its influencing factors, and to interpret the specific mechanisms that affect students’ well-being (Das et al. 2020; Stenlund et al. 2021; Steinmayr et al. 2016; Govorova et al. 2020; Courtney et al. 2023).

Identifying students’ subjective well-being (SWB): ideas and measurements

Well-being/happiness refers to objective individual fulfillment, self-fulfillment, and self-improvement independent of people’s beliefs, as reflected in research focused on psychological well-being and social well-being (Ryff et al. 2004). Psychological well-being mainly refers to a good state of human psychological functioning, which differs from the happiness orientation of SWB and focuses on self-perfection, self-realization, and self-achievement, which are not diverted by one’s subjective will (Ryff and Keyes 1995). Ryff and Keyes (1995) proposed a six-dimensional model of psychological well-being: self-acceptance, positive relationships, sense of life purpose, sense of environmental control, independence, and personal growth. Many past studies have shown that psychological well-being is influenced by factors such as gender, age, academic success, self-efficacy, and social support (Ryff 1989; Antaramian 2017; Czyżowska Gurba (2021); Shin, Park (2022)). Social well-being refers to an individual’s self-assessment of the quality of their relationships with others, the collective, and society, as well as their living environment and social functioning. This concept has five main dimensions: social integration, social contribution, social harmony, social identity, and social realization (Keyes 1998). Hill et al. (2012) found that the initial level of social well-being was positively correlated with the level of the “big five” personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness), and changes in social well-being were consistent with changes in these traits over time (Keyes, Ryff (1998); Keyes, Shapiro (2001); Bradbury et al., 2015). Subjective well-being is a comprehensive cognitive appraisal of overall life satisfaction that arises from an individual’s fulfillment of his or her needs and is accompanied by positive emotional experiences (Diener 2000). The basic characteristics of SWB include: (1) subjectivity, with measurement based on the evaluator’s internal standards rather than evaluation by others; 2) stability, which mainly reflects long-term rather than short-term emotional responses, with life satisfaction being a relatively stable value; and (3) wholeness, which encompasses a comprehensive evaluation, including evaluation of emotional response and cognitive judgment (Diener 1984, 1999).

For the measurements of subjective well-being, in 2011, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) launched the Happiness Index, which is an online test that allows ordinary people to rank their country’s performance in terms of how important things and quality of life are to them. The resulting index is used to measure people’s life satisfaction. In this system, measurement of individual happiness comprises 11 dimensions, which can be divided into two parts. The first part encompasses material conditions, including income, health, work, livelihood, and housing. The second captures quality of life, including health status, work-life balance, education and skills, social connections, civic engagement and governance, environmental quality, personal safety, and SWB. Student happiness refers to students’ overall evaluation of and satisfaction with their study and life. This concept has been measured in various ways. In 2007, South Australia published a learner wellbeing framework that spanned from a child’s birth to Year 12. This paper defined the composition of students’ happiness using five dimensions (cognitive, emotional, physiological, social, and spiritual). Opdenakker and Van Damme (2000) constructed a student happiness questionnaire that covered school happiness, social integration in the classroom, teacher-student relationships, interest in learning tasks, motivation for learning tasks, attitude toward homework, attention in the classroom, and academic self-concept. Huebner et al. (2000) measured students’ SWB using six aspects of satisfaction: family, self, friends, school, living environment, and overall life. Anne, Rimpelä (2002) proposed that students’ school happiness included school conditions, social relationships, self-actualization methods, and health status. Soutter et al. (2014) summarized key terms related to happiness in the fields of economic sociology, psychology, and health science. Those authors defined subjective and objective indicators in contemporary research to detect happiness and proposed a seven-dimensional model of student happiness: school conditions, self-actualization mode, social connection, feeling, thinking, function, and effort.

In this study, PISA well-being measurement framework were applied. The OECD has focused on student happiness since PISA 2015. PISA 2015 defined student well-being as the mental, cognitive, physical, social, and physical functions and abilities that students needed to lead happy and fulfilling lives (OECD 2017). In the process of constructing the content of student happiness and assessing content and indicators, the OECD drew on research results for SWB and psychological well-being, and measured student happiness using four dimensions (psychological, cognitive, social, and physical fitness) with reference to its own “Good Life Index.” PISA 2018 defined happiness as people’s quality of life and standard of living and considered happiness as a multidimensional structure that included the whole and the individual, the subjective and the objective (OECD 2019). From PISA 2015 to PISA 2018, the OECD’s focus on happiness shifted from mere ability input to the whole of students’ lives, reflecting an emphasis on the all-round development of students’ happiness. PISA 2018 divided happiness into four dimensions: overall life happiness, personal happiness, on-campus happiness, and off-campus happiness. Overall life happiness only encompassed subjective indicators, whereas self-happiness, on-campus happiness, and off-campus happiness contained both subjective and objective indicators. The PISA 2018 questionnaire adopted the self-report questionnaire method. In addition to measuring happiness in different dimensions, PISA 2018 also offered suggestions for a composite happiness index. For example, social happiness comprised on- and off-campus happiness, and subjective happiness involved life satisfaction, emotional balance, and self-fulfilling happiness. PISA 2022 continued the well-being measurement framework and measurement methods used in PISA 2018 but made overall improvements and adjustments to some items in the questionnaire based on students’ learning and living conditions during the COVID-19 period. The regular student well-being questionnaire included a health and well-being sub-module with questions about students’ overall life satisfaction, online activities, and potentially problematic online behaviors (e.g., spending a lot of time on social networks/video games). The first question was directly related to students’ SWB, and the latter two questions aimed to understand the impact of online activities on students’ health and well-being.

As subjective well-being (SWB) models have become increasingly nuanced, more studies have sought to validate existing SWB measurement tools considering recent theoretical advancements and societal changes, proposing refinements and enhancements accordingly. Chien et al. (2020) found that the Chinese version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SHS-C) was correlated with two theoretically distinct yet related constructs (self-esteem and interpersonal harmony) and demonstrated high correlation with multidimensional subjective well-being (MSWB) measures, suggesting interchangeability between the two. Schnettler et al. (2021) evaluated the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) among university students in Chile and Spain, confirming that the scale enables significant latent mean comparisons across cultural samples. Roberson and Renshaw (2022) extended previous validation efforts by scrutinizing the SSWQ’s previously proposed factor structure (i.e., four group factors; one general factor) and score reliability using contemporary sample data. They discovered that fewer items could be utilized to effectively gauge school-specific subjective wellbeing as reported by adolescents.

Exploring effects and influential factors on students’ subjective well-being

Most research on SWB has focused on its effects and influencing factors. They have shown that SWB played a positive role in promoting physical and mental health. For example, Baiden et al. (2016) found that SWB had an independent protective effect against psychological distress among adults. Lucas-Molina et al. (2018) showed that SWB could help prevent bullying and reduce suicidal tendencies among adolescents. Furrer et al., (2019) found that SWB could reduce patients’ pain intensity and depressive symptoms to some extent. VanderWeele et al. (2012) showed that loneliness significantly predicted SWB longitudinally. SWB is composed of four main aspects: life satisfaction, positive emotion, negative emotion, and domain satisfaction (Casas 2011; Courtney et al. 2023). In addition, there are also some factors that affect students’ subjective well-being (Das et al. 2020; Stenlund et al. 2021; Lawler et al. 2017; Lee and Yoo 2015; Steinmayr et al. 2016; Govorova et al. 2020; Crothers et al. 2010; Courtney et al. 2023). For example, Govorova et al. (2020) conducted a network analysis based on data from the PISA 2018 international assessment and showed that school factors generally had a small impact on student well-being, whereas teaching enthusiasm and support promoted a positive school climate. Rodriguez et al., (2020) examined the differences between native and immigrant students using the PISA 2018 well-being indicators and found that there was no difference in life satisfaction between native and immigrant students, but native students performed better in terms of positive impact at school, self-efficacy (resilience), and belonging. Resilience, motivation to achieve learning goals, competitiveness, perception of cooperation in school, and social contact with parents positively impacted students’ mathematical literacy.

Examining school bullying: current studies regarding to influencing factors

School bullying, school connectedness and students’ subjective well-being

School bullying is closely corrected with school connectedness and students’ subjective well-being (Seon and Smith‐Adcock 2021; Yubero et al. (2023); Gomez-Baya et al. 2022; Carretero Bermejo et al. 2022). For example, school connectedness was confirmed to be closely related to peer bullying behavior and students’ well-being (Varela et al. 2019; 2020). The bullying behavior is negatively correlated with various indicators of subjective well-being, and school-level SES has a negative impact on subjective well-being, suggesting that other relevant characteristics should be fully considered when formulating prevention strategies. Borualogo, Casas (2023) explored sibling bullying and school bullying in three age groups (8, 10, and 12 years) in Indonesia, and how these bullying behaviors (physical, psychological, and verbal) affect children’s subjective well-being. Being spanked by other children in school had no significant effect on CW-SWBS in grades 2 and 4, and only a low significant effect on grade 6. Being left out in class has a significant impact on all grades. Being called an unkind name by a child at school had a significant effect on grades 2 and 4, but not on grade 6. Many Indonesian children who experience bullying seem to have adapted to physical bullying, maintaining their SWB levels through buffering (behavior and good relationships). Huang (2021) focused on the relationship between bullying and subjective well-being and revealed a negative correlation between bullying and life satisfaction and positive emotions, as well as a positive correlation with negative emotions. Gempp, González-Carrasco (2021) also confirmed a significant reciprocal influence between school satisfaction and overall life satisfaction, with a greater impact from school to life satisfaction.

School bullying, a sense of belonging and emotional intelligence

The previous studies have shown that school bullying and a sense of belonging in school are significant factors affecting students’ subjective well-being during or before and after the pandemic (Varela et al. 2019; 2020. For instance, it is found that aggressive and victim behaviors are negatively correlated with indicators of happiness, while positively correlated with social support and satisfaction with different developmental environments. The positive interpersonal relationships, a key indicator of school atmosphere, are significantly positively correlated with school happiness. It is also acknowledged that school bullying is associated with emotional intelligence (Dias-Viana et al. 2023; Borualogo, Casas (2023)). For example, Quintana-Orts et al. (2021) analyses the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) facets, satisfaction with life, bullying and cyberbullying in adolescents. The correlation analyses showed that most EI facets were positively related to satisfaction with life and negatively with both types of violence. As was expected, bullying and cyberbullying victims and bully-victims scored lower in satisfaction with life and most EI facets. Controlling for sex, age, and grade, self-emotion appraisal, use of emotions and regulation of emotion were the best predictors of life satisfaction in bully–victims of bullying and cyberbullying.

Potential scientific contribution

This study offers several potential scientific contributions as follows: first, for the research gap, there is a dearth of exploring students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic using a large-scale data with comparative perspectives. The previous research on students’ well-being has mostly focused on cross-sectional studies or longitudinal studies with shorter time spans before or after the pandemic, with few comparative studies on the performance of students’ subjective well-being and its influencing factors before and after the pandemic. Second, for the specific research topic, this study contributes mitigating the research gap regarding to examining the factors that influenced students’ subjective well-being (SWB) in different countries and regions, especially figuring out the changes in these factors from a time span. In particular, the samples selected in previous studies are mostly limited to one or several countries (regions) in proximity, with few large-sample studies on a global scale. Compared with the previous published research, this study expands the countries and regions, including the United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China. Third, this study also contributes to enriching and expanding the dimensions and influencing factors of identifying the idea of students’ subjective well-being (SWB). For example, the previous studies on the influencing factors of students’ happiness focus on one specific aspect, such as the individual, family, or school, lacking a comprehensive consideration of various influencing factors. In addition, for the previous publication regarding to students’ subjective well-being, the exploration of the relationships between influencing factors is somewhat insufficient, especially regarding the relationship between school bullying, school belonging, and subjective well-being. Compared with the published related research, this study brings multiple influencing factors that contributes to providing a more holistic viewpoint. All above mentioned potential scientific contributions of this study is presented and analyzed in this study.

Research questions

To address those gaps above, this study utilizes data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 and 2022 to identify the influencing factors of students’ subjective well-being in six countries and regions (United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China) from 2018 to 2022. The core focus of this study is the level of subjective well-being of students who participated in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022, as well as the changes in performance and influencing factors between 2018 and 2022 and the relationships between these factors.

The guiding research questions of this study are as follows:

Q1: What are the characteristics of students’ subjective well-being (SWB) in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022? What are the differences?

Q2: How do individual, school, and family factors affect students’ subjective well-being (SWB) in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022? What are the differences?

Q3: What are the relationships between different influencing factors? What are the differences between their performance in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022?

Research hypotheses

Along with the previous literature review and research questions, the research hypotheses are offered. Question 1 aims to provide a comprehensive presentation of the actual situation of students’ subjective well-being in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022, not only describing the data for 2018 and 2022 separately but also comparing the differences between the two years to observe whether there have been changes in students’ subjective well-being before and after the pandemic. Question 2 primarily explores what factors influence students’ subjective well-being, what their characteristics were in 2018 and 2022, and how they affect subjective well-being. Are there differences between the different years? Question 3 mainly discusses the relationships between influencing factors, based on the actual situation of research paths and related factors found in previous surveys on subjective well-being. Along with the previous studies and in response to Research Question 3, this study proposes the following two research hypotheses.

H1: School belongingness mediates the impact of school bullying on students’ subjective well-being.

H2: The quality of students’ intimate relationships (including peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships) moderates the relationship between family socioeconomic status (ESCS) and students’ subjective well-being.

Method

Research design and data source

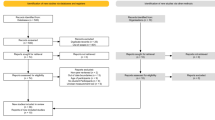

PISA is a triennial survey of 15-year-olds that assesses the extent to which they have the key knowledge and skills necessary to fully participate in society. In 2018, 79 countries (regions) around the world participated in the PISA assessment, and students from nine of these countries (regions) participated in supplement questionnaire on well-being. In 2022, 81 countries (regions) worldwide participated in the PISA assessment, and students from 15 countries (regions) completed the supplement questionnaire on well-being. This study selected the only six countries (regions) that participated in 2018 and 2022 supplement questionnaires on well-being as research objects. These countries (regions) were the UAE, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China. All six of these countries (regions) belongs to the group of happy countries (regions). In a Gallup-Healthways Well-Being poll conducted in 2014, Panama was ranked first out of 135 countries, with Mexico at 17th, the UAE at 18th, Ireland at 28th, and Spain at 35th (Painter 2014). In addition, the United Nations World Happiness Report 2018 ranked Ireland in the 14th position out of 156 countries, the UAE is ranked 20th, Mexico is ranked 24th, Panama is ranked 27th, Spain is ranked 36th, and Hong Kong, China is ranked 76th (Sachs et al., (2018)). As representative high happiness countries (regions) in the Americas, Europe and Asia, the selection of these six countries (regions) as the object of study has strong referability. In total, 153,052 students were assessed in 2018 and 2022, of which 78,257 were assessed in 2018 and 74,795 were assessed in 2022. We used SPSS 26.0 software to explore the characteristics, influencing factors, and influencing paths of students’ SWB in PISA 2018 and 2022 data (Table 1).

Description of variables

In this study, students’ SWB was selected as the explained variable. Explanatory variables were selected from three levels (individual, school, and family). Explanatory variables were selected based on previous studies, with reference to the same parts of PISA 2018 and PISA 2022 tests and questionnaires related to subjective well-being. At the individual level, we selected gender, health level, peer relationships, and student achievement. At the school level, school bullying, school belonging, need to repeat the grade, and teacher-student relationships were selected. At the family level, we evaluated family economic status and parent-child relationships. PISA 2018 defined SWB as “a good state of mind that includes all the positive and negative assessments people make about their lives and people’s emotional responses to their experiences.” This definition was reflected in three measures: life evaluation, which is a person’s reflective assessment of their life or “overall life satisfaction”; mood, which refers to a person’s emotional state at a particular point in time; and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, or the happiness that comes from living rationally and actively (OECD 2019). PISA 2022 considered “overall life satisfaction” as the core element of SWB, and only retained this factor in the SWB measurement (OECD 2023a). Therefore, this study used overall life satisfaction as the only index to measure SWB. The overall life satisfaction test item in the PISA assessment was drawn from the first question of the student questionnaire (ST016), which asked students to rate their life satisfaction on a scale from 0 (“not satisfied at all”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”). Students that scored 0–4 were classified as “dissatisfied,” those that scored 5 or 6 scale were considered “somewhat satisfied,” those scoring 7 or 8 were “moderately satisfied,’ and those scoring 9 or 10 were “very satisfied” (OECD, 2019). In this study, students’ life satisfaction was recoded using a scale from 1 to 4 in accordance with the PISA assessment instructions: 1 = “not satisfied,” 2 = “somewhat satisfied,” 3 = “moderately satisfied,” and 4 = “very satisfied.”

Health level reflected students’ assessment of their own health based on the PISA well-being questionnaire (WB150); this was scored from 1 to 4 (1 = “very good health,” 2 = “good health,” 3 = “normal health,” and 4 = “poor health”). To facilitate data processing and analysis in this study, reverse recoding was performed in the process of specific data manipulation. Peer relationships referred to students’ satisfaction with their relationships with their friends. This variable was drawn from the fourth question in the happiness questionnaire (WB155) and was scored from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 4 (“very satisfied”). Academic achievement included reading literacy achievement, math literacy achievement, and science literacy achievement. The PISA literacy score has 10 plausible values obtained based on item response theory. During data processing, the final score is synthesized by weighting specific items provided by PISA, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy levels. School bullying was evaluated by composite indicators (e.g., the number of incidents experienced and type of bullying) and was standardized with a mean value for OECD students of 0 and standard deviation of 1. School belonging was assessed with a combination of indicators (e.g., loneliness in school, making friends, and peer relationships), and was standardized with a mean value for OECD students of 0 and standard deviation of 1. A student’s need to repeat the grade was evaluated, with a score of 0 meaning no need to repeat, and a score of 1 indicating the grade needed to be repeated. Evaluation of teacher-student relationships involved students’ satisfaction with the relationships between themselves and their teachers and was drawn from the ninth question of the happiness questionnaire (WB155). Scores for this item ranged from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 4 (“very satisfied”). The family economic status was captured by a combination of parental education level, occupational status, family wealth, and other indicators, and was standardized with a mean value for OECD students of 0 and standard deviation of 1. The parent-student relationship reflected students’ satisfaction with their relationships with their parents/guardians. This was drawn from the eighth question in the happiness questionnaire (WB155) and scored from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 4 (“very satisfied”) (Table 2).

Results

Characteristics of students’ subjective well-being (SWB) in 2018 and 2022

In the PISA analysis framework, life satisfaction is a core element of SWB (OECD 2023). As noted above, the PISA 2022 SWB measurement was solely based on “overall life satisfaction”; therefore, this was the only indicator of SWB used in this study. Measurement of overall life satisfaction classified students’ SWB into four categories “dissatisfied” (0–4), “somewhat satisfied” (5–6), “moderately satisfied” (7–8), and “very satisfied” (9–10). In this study, these scores were coded as 1, 2, 3, and 4. The six countries (regions) included in this study (UAE, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China) showed significant differences between students’ SWB in 2018 and 2022 (t = 28.731, p < 0.001). The mean SWB of students in 2018 (2.91 ± 1.044) was significantly higher than that in 2022 (2.75 ± 1.037), with an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.154; as this was less than 0.2, it indicated a small effect size.

The proportion of students whose SWB was classified as “very satisfied” was 35.8% in 2018, but dropped to 28.2% in 2022, reflecting a decrease of 7.6 percentage points. Correspondingly, compared with 2018, the proportions of students whose SWB in 2022 was “moderately satisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” and “dissatisfied” increased, which indicated that students’ SWB level had decreased significantly in 2022 compared with 2018 (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Characteristics of individual, school, and family factors influencing students’ subjective well-being SWB in 2018 and 2022

Independent samples t-tests were performed for continuous variables and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Academic achievement (mathematics, reading, and science achievement) was not compared using an independent samples t-test because of changes in the measurement standards between the two datasets (Table 4).

At the individual level, students’ health (t = 34.788, p < 0.001) and peer relationships (t = 64.452, p < 0.001) were significantly lower in 2022 compared with 2018. The Cohen’s d values for both variables were less than 0.2, indicating small effect sizes. In terms of academic achievement, the mathematics and reading literacy scores of students in 2022 were lower than those in 2018, whereas the students’ science literacy scores in 2022 were slightly higher than those in 2018 Fig. 2.

At the school level, students were significantly less bullied in 2022 than in 2018 (t = 56.712, p < 0.001); the Cohen’s d value was 0.309, which showed the largest effect size among all factors. In 2022, students’ school belonging (t = 27.061, p < 0.001) and teacher-student relationships (t = 55.551, p < 0.001) had significantly decreased compared with 2018. The Cohen’s d values for both variables were less than 0.2, indicating small effect sizes. Pearson’s chi-square test results for the need to repeat the grade showed that the rate of repeat students was significantly lower in 2022 than in 2018 (14.5% vs. 18.8%; χ2 = 508.113, p < 0.001). The Cramer’s V value was 0.058 and the effect size was small.

At the family level, students’ family economic status was significantly higher in 2022 than in 2018 (t = −24.371, p < 0.001), whereas students’ parent-child relationships were significantly lower in 2022 than in 2018 (t = 61.576, p < 0.001). The Cohen’s d values for both variables were less than 0.2, indicating small effect sizes.

Correlational and regression analyses of factors influencing students’ subjective well-being (SWB)

In 2018, students’ SWB was significantly correlated with influencing factors at the individual, school, and family levels (p < 0.01), with parent-child relationships showing the strongest correlation with SWB (r = 0.344). At the individual level, the correlation between health level and SWB was the strongest (r = 0.03). Furthermore, the scores for all literacy categories showed negative correlations with SWB, although reading literacy showed a slightly stronger correlation with SWB than the other two literacy items (r = −0.67). At the school level, school belonging showed the strongest correlation with SWB (r = 0.280). Campus bullying and need to repeat the grade were negatively correlated with SWB, with the correlation between campus bullying and SWB being slightly stronger (r = −0.190). At the family level, the correlation between SWB and parent-child relationships (r = 0.014) was much stronger than that between SWB and family economic status (r = 0.344) (Table 5).

In 2022, SWB was significantly correlated with individual, school, and family associated factors (p < 0.01), with health level showing the strongest correlation with SWB (r = 0.375). At the individual level, all literacy categories were negatively correlated with SWB, although reading literacy had a slightly stronger correlation with SWB than the other two items (r = −0.79). At the school level, the correlation between teacher-student relationships and SWB was the strongest (r = 0.274). Campus bullying and need to repeat the grade were negatively correlated with SWB, with the correlation between campus bullying and SWB being slightly stronger (r = −0.199). At the family level, the correlation between SWB and parent-child relationships (r = 0.361) was much stronger than that between SWB and family economic status (r = 0.040) (Table 6).

The total explanation rate of all factors influencing SWB in 2018 was 22.9%, and that for 2022 was 26.9%. In 2018, the R2 values for changes in the influence of personal factors, school factors, and family factors on SWB were 0.136, 0.068, and 0.024, respectively. Among the individual factors, all variables had significant effects on SWB except mathematics and science literacy levels (p > 0.05 vs. p < 0.05). Reading literacy had a significant negative impact on students’ SWB (β = −0.085, t = −8.217, p = 0.000). At the level of school factors, all variables had significant effects on SWB (p < 0.01), although campus bullying (β = −0.096, t = −22.345, p = 0.000) and the need to repeat the grade (β = −0.02, t = −4.836, p = 0.000) had negative effects on students’ SWB. At the family factors level, family economic status had no significant impact on students’ SWB (p > 0.05), whereas parent-child relationships had a significant positive impact on students’ SWB (β = 0.192, t = 39.593, p = 0.000).

In 2022, the R2 values for changes in the influence of personal, school, and family factors on SWB were 0.190, 0.053, and 0.026, respectively. All individual-level factors had significant effects on SWB (p < 0.01). Among these factors, reading literacy (β = −0.114, t = −14.962, p = 0.000) and science literacy (β = −0.074, t = −8.005, p = 0.000) had significant negative effects on students’ SWB. At the school level, all factors except the need to repeat the grade (p > 0.05) significantly impacted SWB (p < 0.01), with campus bullying (β = −0.104, t = −28.988, p = 0.000) showing a negative impact on students’ SWB. All family-level family factors had significant effects on SWB (Tables 7 and 8).

Mediating role of students’ campus belonging

The relationship between campus bullying and students’ SWB was also affected by by mediating variables. This study clarified whether campus bullying impacted students’ SWB through school belonging and examined the mediating effect of school belonging on students’ SWB. With students’ school belonging as the mediating variable, a regression model was established to test its mediating role in the impact of campus bullying on students’ SWB in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022 data.

In the mediating model for PISA 2018 data, Model 1 used campus bullying as the independent variable and students’ SWB as the dependent variable. The regression coefficient for the independent variable was c = −0.190, which passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001). The theory was based on the mediating effect and showed that for every unit increase in bullying, students’ SWB decreased by 0.190 units. The first step of the mediation effect test was completed. In Model 2, campus bullying was the independent variable and school belonging was the dependent variable. The regression coefficient for the independent variable was a = −0.328, which passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001). This showed that for every unit increase in bullying, students’ sense of belonging to school decreased by 0.328 units. Finally, Model 3 used school belonging as the independent variable and students’ SWB as the dependent variable. The regression coefficient for school belonging was b = 0.280, which passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001), indicating a significant indirect effect. For every 1 unit increase in school belonging, students’ SWB increased by 0.280 units (Table 9).

Testing of the mediating effects for school belonging, campus bullying, and students’ SWB showed the c value was −0.109 (p < 0.001), suggesting that school belonging had a significant mediating effect in the relationship between campus bullying and students’ SWB in PISA 2018 data. Moreover, this model showed a partial mediation effect, and the ratio of the mediation effect to the total effect was: effectm = ab/c = (−0.328) × 0.280/( − 0.190) = 0.483 (Table 10).

In the mediating model for PISA 2022 data, Model 1 used campus bullying as the independent variable and students’ SWB as the dependent variable. The regression coefficient for the independent variable was c = −0.199, which passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001). The theory was based on the mediating effect and showed that for every unit increase in bullying, students’ SWB decreased by 0.199 units. The first step of the mediation effect test was completed. In Model 2, school bullying was the independent variable and school belonging was the dependent variable. The regression coefficient for the independent variable was a = −0.253, which passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001). This showed that for every unit increase in bullying, students’ sense of belonging to school decreased by 0.253 units. Finally, in Model 3, with school belonging as the independent variable and students’ SWB as the dependent variable, the regression coefficient for school belonging was b = 0.264. This passed the significance test at the level of 0.001 (p < 0.001), indicating a significant indirect effect; for every 1 unit increase in school belonging, students’ SWB increased by 0.264 units.

The mediating effect between the three variables was tested and the c value was −0.144 (p < 0.001), which suggested that the mediating effect of school belonging in the relationship between bullying and students’ SWB was significant in PISA 2022 data. The analysis revealed that the model showed a partial mediation effect, and the ratio of the mediation effect to the total effect was: effectm = ab/c = (−0.253) × 0.264/( − 0.199) = 0.336.

The results of the mediation model testing showed that both the PISA 2018 and PISA 2022 mediation models were valid. Campus bullying significantly negatively predicted students’ SWB and significantly positively predicted students’ school belonging. School belonging significantly positively predicted students’ SWB. When both bullying and school belonging were entered into the regression equation, bullying significantly negatively predicted students’ SWB and school belonging positively predicted students’ SWB.

Moderating effect of students’ interpersonal relationships

The relationship between students’ family economic status and students’ SWB was associated by students’ interpersonal relationships (i.e., peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships). The relationship between students’ family economic status and students’ SWB was associated their peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships. The regression results for PISA 2018 data showed that students’ SWB was significantly impacted by their family economic status and interpersonal relationships (with peers, teachers, and parents) and the interaction of these factors. The regression equation was constructed as follows.

Among the variables affecting students’ SWB, the main effect of family economic status was significant; the higher the family economic status, the lower students’ SWB (by 0.026 points). The main effect of interpersonal relationships was significant. Students with good relationships had higher SWB, with these students showing higher SWB by 1 standard score and 0.364 points. Interpersonal relationships had a significant moderating effect on students’ SWB (i.e., the F-value changed significantly). A higher interpersonal relationship score indicated students’ family economic status had a greater impact on their SWB. The regression results for PISA 2022 showed that students’ SWB was significantly affected by their family economic status, relationships with peers, teachers, and parents, and the interaction of these factors. The regression equation was constructed as follows.

Among the variables affecting students’ SWB, the main effect of family economic status was significant, with a higher the family economic status indicating a higher level of SWB. When the family economic status increased to one standard point higher than the average, students’ SWB increased by 0.011 points. The main effect of interpersonal relationships was significant. Students with good relationships had higher SWB, and a relationship score higher by 1 standard point increased SWB by 0.374 points. Relationships with peers, teachers, and parents had a significant moderating effect on students’ SWB (i.e., the F-value changed significantly). The higher the interpersonal relationships score, the greater the impact of students’ family economic status on their SWB. The results of the adjustment model showed that the models for both PISA 2018 and PISA 2022 were valid. Interpersonal relationships significantly positively affected both students’ SWB and the relationship between students’ family economic status and their SWB. However, in the moderating model, we found that the impact of family economic status on students’ SWB in PISA 2018 and PISA 2022 were completely opposite. Family economic status negatively predicted students’ SWB in PISA 2018, but positively predicted students’ SWB in PISA 2022.

Discussion

This study contributes to addressing the gap in the literature by utilizing large-scale datasets and a comparative perspective to investigate the relationships between students’ subjective well-being, bullying, and sense of belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has predominantly focused on cross-sectional studies conducted before and after the onset of the pandemic. In contrast, our study compares PISA 2018 and PISA 2020 data for six countries (the UAE, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China). Our findings reveal a notable decline in students’ levels of subjective well-being in 2022 compared to 2018, with a notable reduction of 7.6 percentage points in the proportion of students reporting they are “very satisfied” with their lives. Previous studies showed that social changes had a subtle impact on people’s psychology and behavior. Major public health events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can therefore lead to lower levels of SWB among adolescents and may affect their mental health in the long term. This empirical evidence underscores the profound effect of the pandemic on students’ emotional states and overall life satisfaction, providing critical insights for educational stakeholders to address the well-being challenges faced by students in the post-pandemic era.

Evaluation of academic achievement showed that the 2022 mathematics and reading literacy scores for the six studied countries (regions) had decreased from 2018, although the science literacy scores increased slightly, which was consistent with the general trend for all countries (regions) reported in the PISA 2022 results. The PISA 2022 results showed an unprecedented decline in mathematics and reading test scores among young people around the world, with the sharp drop in mathematics scores being three times larger than any previous continuous change; this decline in student achievement was partly linked to school closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD 2023b).

Students in 2022 were significantly less attached to school than they were in 2018. “School belonging” refers to the degree to which students feel accepted, included, respected, and encouraged by school members as an important part of the school environment (Goodenow, Grady (1993)). Students in 2022 experienced significantly less bullying than in 2018, despite the PISA report showing that the incidence of bullying in schools had increased in recent years; however, the rate decreased by 2–3 percentage points between 2018 and 2022 (OECD 2023b). This is clearly a positive trend and may be attributable to the increased focus on and interventions for bullying. However, it may also be related to students spending relatively little time in school during the COVID-19 pandemic. Limiting bullying in schools must be a joint effort by policymakers, principals, and teachers.

The quality of students’ interpersonal relationships (peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships) in 2022 was significantly lower than in 2018. Peer relationships showed the largest effect size, which indicated the change in peer relationship between the two datasets was the greatest. This change is largely attributable to school closures and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, as there were fewer opportunities for face-to-face interaction and collaboration and poor-quality online socializing, resulting in loneliness, depression, and anxiety that further affected peer relationships. The PISA report showed that 16% of students in OECD countries reported feeling lonely (OECD 2023b). At the parent-child level, the PISA report noted that most education systems experienced a significant decline in parental involvement in student learning at school between 2018 and 2022. At the teacher-student relationship level, teachers providing time to meet students’ needs was noted as an important part of effective teaching (OECD 2023b).

The factor that showed the highest correlation with SWB changed from parent-child relationships in 2018 to level of health in 2022. This transition reflects the heightened public awareness of health precipitated by the pandemic and underscores the pivotal role of health in determining individuals’ levels of happiness and overall well-being. Numerous studies have shown that common psychological effects of COVID-19 illness included increased levels of uncertainty and helplessness, stress, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychological distress, depression, and higher prevalence of harmful behaviors (e.g., self-harm, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and substance use) (Blasco-Belled et al. (2024); Bonati et al. 2022; Hernandez-Diaz et al. 2022; Leung et al. 2022; Pappa et al. 2022; Serafini et al. 2020; Thakur and Jain 2020). Birch, Ladd (1998) believed that good teacher-student relationships were conducive to students’ positive feelings toward school and classmates and promoted students’ mental health development (Nickerson and Nagle 2004; Tomé et al. 2014). This finding highlights the imperative for educational and health policies to integrate health promotion and mental health support, recognizing the interplay between physical health and psychological well-being, particularly in the context of global health crises.

The study elucidates the trends in the impact of personal, school-related, and familial factors on students’ subjective well-being. PISA data showed that personal factors had the largest impact on students’ SWB, and this impact had increased from 2018 to 2022. The influence of school factors decreased, and the influence of family factors increased (Dixson 1995). Although academic achievement was one of the main activities in the life of 15-year-old students, high academic achievement did not necessarily lead to higher life satisfaction and low academic achievement did not automatically translate into lower life satisfaction. This comprehensive analysis offers insights into how different facets of a student’s environment and individual characteristics converge to shape their overall sense of happiness and contentment, contributing to a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted nature of well-being in educational contexts.

This study corroborates the mediating role of school belonging in the relationship between bullying experiences and students’ subjective well-being. More bullying experiences resulted in a lower sense of belonging to school, which in turn led to lower SWB. This underscores the critical importance of fostering a strong sense of school belonging as a preventive measure against bullying and to enhance students’ overall happiness and well-being. This finding aligns with prior research, indicating a significant inverse association between school bullying and students’ subjective well-being, while also highlighting the role of school belonging as a moderator in this relationship (Seon and Smith‐Adcock 2021; Huang 2020; Liu et al. 2020; Savahl et al. 2019). Compared to previous research, our study provides more evidence from multiple countries and young adolescents. The results indicate that school belongingness may be a crucial focus for the prevention and intervention of bullying in schools. Therefore, we recommend incorporating research evidence on school belongingness into the development of anti-bullying programs, such as the conceptual framework for school belongingness proposed by K. A. Allen et al. (2016), to take targeted actions to enhance students’ subjective well-being. The research by Juvonen et al. (2016) also supports this recommendation, demonstrating that when the school environment is transformed by increasing teacher and peer support, more victimized students will have a more positive view of their school and experience less emotional distress.

The research outcomes demonstrate that the relationship between students’ family economic status and SWB was influenced by students’ peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships, and these moderating effects were significant (Silișteanu et al., (2022)). This suggests an additional impact of relational quality on well-being across varying socioeconomic contexts, underscoring the importance of nurturing positive social connections as a crucial component of enhancing students’ overall happiness and life satisfaction, irrespective of their economic background. A previous study showed that parents of students from families with higher socioeconomic status had a higher education level, were more consciously involved in their children’s education and growth, and more willing to spend time communicating with their children to solve problems in study and life than parents with lower socioeconomic status (Lereya et al. 2013). It has been noted that the construction of parent-child care and support bonds may improve students’ adaptability to school learning and social communication (Juvonen et al. 2016; Rask et al. 2003; Rivara, Le Menestrel (2016); Saarento et al. 2015). In addition, during the pandemic, Spain explored applying dialogic literary gatherings virtually in the home environment to enhance children’s communication and interaction during the lockdown, fostering a safe and supportive learning environment within the family, thereby improving children’s well-being (Ruiz-Eugenio et al. 2020).

Limitations and further research directions

This study had some limitations as follows. First, although this study incorporated data from 2018 and 2022, the research design remains cross-sectional and unable to draw inferences related to causality. Future studies can adopt a longitudinal research design to provide more detailed and accurate data, determining the causal relationships relevant to this research in the field of education. Secondly, the research results are primarily based on a sample of 15-year-old adolescents from five countries and regions, including the United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China, without an in-depth analysis of the differences between countries. More contextual background analysis could be added in future studies. The sample size could be expanded to perform cross-country and cross-culture analyses in further studies. For example, the age and region of the participants should be considered to enhance the representativeness of the research results. Finally, further studies may explore the mechanisms influencing of students’ SWB, to explore the impact of individual, family, and other school factors on students’ subjective well-being, as well as the pathways in which these factors influence students’ subjective well-being and propose practical ways to improve students’ SWB and promote their healthy physical and mental growth. Additionally, it should be noted that while this study aims to better understand some of the influencing factors related to students’ subjective well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, it does not cover all objective factors that existed during the pandemic (for example, different educational models in various countries, varying degrees of COVID-19 exposure, different public health requirements, and different related intervention measures).

Conclusion

Based on PISA data for 2018 and 2022, this study analyzed the changing trends of students’ SWB and associated influencing factors in the UAE, Ireland, Panama, Mexico, Spain, and Hong Kong, China. We aimed to clarify the performance characteristics, influencing factors, and influencing paths of students’ SWB. The results showed a significant difference in the SWB of students between 2018 and 2022. From 2018 to 2022, the factor that was most closely related to SWB changed from parent-child relationships to health level. Individual factors had the greatest influence on students’ SWB and showed an increase, the influence of school factors weakened, and the influence of family factors increased. Parent-child relationships significantly predicted students’ SWB, and campus bullying significantly negatively impacted students’ SWB. The negative impact of repeating grades on students’ SWB weakened from 2018 to 2022, whereas the mechanism by which academic achievement impacted SWB became more complex. In addition, the analysis of the mediating and moderating effects showed that students’ school belonging played a mediating role in the relationship between bullying and students’ SWB, and the influence of students’ family economic status on their SWB was moderated by students’ peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and parent-child relationships. Through the comparative analysis, this study provides profound insights into the alterations of students’ subjective well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic and the determinants thereof. It directly informs educational and psychological intervention strategies, such as incorporating enhancements of school belonging into anti-bullying programs and tailoring emotional support and family engagement approaches for students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. These findings offer empirical grounding for educational policymakers and practitioners to develop more efficacious initiatives aimed at mental health promotion and well-being enhancement, thereby addressing the psychosocial needs of students in a post-pandemic educational landscape.

Data availability

The paper includes a dataset that has been deposited in the journal’s Dataverse repository. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UVLSIY.

References

Allen KA, Vella-Brodrick D, Waters L (2016) Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. Educ Developmental Psychologist 33(1):97–121

Anne K, Rimpelä M (2002) Wellbeing in school: A conceptual model. Health Promotion Int 17(1):79–87

OECD (2019a) PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris

Antaramian S (2017) The importance of very high life satisfaction for students’ academic success. Cogent Educ 4(1):1–10

Baiden P, Tarshis S, Antwi-Boasiako K, den Dunnen W (2016) Examining the independent protective effect of subjective well-being on severe psychological distress among Canadian adults with a history of child maltreatment. Child Abus Negl 58:129–140

OECD (2017a) Are students happy? PISA 2015 Results: Students’ Well-Being. PISA. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2023a) PISA 2022 Assessment and Analytical Framework. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris

Birch SH, Ladd GW (1998) Children’s Interpersonal Behaviors and the Teacher-child Relationship. Developmental Psychol 34(2):121–130

Blasco-Belled A, Tejada-Gallardo C, Fatsini-Prats M, Alsinet C (2024) Mental health among the general population and healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of well-being and psychological distress prevalence. Curr Psychol 43(9):8435–8446

Bonati M, Campi R, Segre G (2022) Psychological impact of the quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the general European adult population: a systematic review of the evidence. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 31:e27

Borualogo IS, Casas F (2023) Bullying Victimisation and Children’s Subjective Well-being: A Comparative Study in Seven Asian Countries. Child Indic Res 16(1):1–27

Bradbury, S, Bird, J, Mueller, M, Ricaurte, G, & Schenk, S (2015). Social capital and student well-being in higher education. a theoretical framework. Social Science Electronic Publishing

Carretero Bermejo, R, Nolasco Hernández, A, & Sánchez, LG (2022). Study of the Relationship of Bullying with the Levels of Eudaemonic Psychological Well-Being in Victims and Aggressors. Sustainability., 14(9)

Casas F (2011) Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indic Res 4:555–575

Chien C, Chen P, Chu P, Wu H, Chen Y, Hsu S (2020) The Chinese version of the Subjective Happiness Scale: Validation and convergence with multidimensional measures. J Psychoeducational Assess 38(2):222–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282919837403

Courtney MGR, Hernández-Torrano D, Karakus M, Singh N (2023) Measuring student well-being in adolescence: proposal of a five-factor integrative model based on PISA 2018 survey data. Large-Scale Assess Educ 11(1):20

Crothers LM, Schreiber JB, Schmitt AJ, Bell GR, Blasik J, Comstock LA, Lipinski J (2010) A preliminary study of bully and victim behavior in old-for-grade students: Another potential hidden cost of grade retention or delayed school entry. J Appl Sch Psychol 26(4):327–338

Czyżowska N, Gurba E (2021) Does reflection on everyday events enhance meaning in life and well-being among emerging adults? Self-efficacy as mediator between meaning in life and well-being. Int J Environ Res public health 18(18):9714

Das KV, Jones-Harrell C, Fan Y, Ramaswami A, Orlove B, Botchwey N (2020) Understanding subjective well-being: perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev 41:1–32

Dias-Viana JL, Noronha APP, Valentini F (2023) Bullying Victimization and Mathematics Achievement Among Brazilian Adolescents: Moderated Mediation Model of School Subjective well-being and Perceived Social Support. Child Indic Res 16(4):1643–1655

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychological Bull 95(3):542

Diener E (2000) Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am psychologist 55(1):34

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL (1999) Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bull 125(2):276

Dixson, MD (1995). Children’s relationships models: The central role of communication and the parentchild relationship. Parents, children and communication: Frontiers of theory and research, 43-62

Furrer A, Michel G, Terrill AL, Jensen MP, Müller R (2019) Modeling subjective well-being in individuals with chronic pain and a physical disability: the role of pain control and pain catastrophizing. Disabil rehabilitation 41(5):498–507

Gempp, R, & González-Carrasco, M (2021). Peer Relatedness, School Satisfaction, and Life Satisfaction in Early Adolescence: A Non-recursive Model. Frontiers in Psychology., 12

Gomez-Baya, D, Garcia-Moro, FJ, Nicoletti, JA, & Lago-Urbano, R (2022). A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children. Children (Basel)., 9(2)

Goodenow, C, & Grady, KE (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Educational, 60-71

Govorova E, Benítez I, Muñiz J (2020) Predicting Student Well-Being: Network Analysis Based on PISA 2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(11):4014

Hernández-Díaz Y, Genis-Mendoza AD, Ramos-Méndez MÁ, Juárez-Rojop IE, Tovilla-Zárate CA, González-Castro TB, Nicolini H (2022) Mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Mexican population: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res public health 19(11):6953

Hill PL, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Roberts BW (2012) Examining concurrent and longitudinal relations between personality traits and social well-being in adulthood. Soc Psychological Personal Sci 3(6):698–705

Huang L (2020) Peer victimization, teacher unfairness, and adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating roles of sense of belonging to school and schoolwork-related anxiety. Sch Ment Health 12(3):556–566

Huang L (2021) Bullying victimization, self-efficacy, fear of failure, and adolescents’ subjective well-being in China. Child Youth Serv Rev 127:106084-

Huebner ES, Drane W, Valois RF (2000) Levels and demographic correlates of adolescent life satisfaction reports. Sch Psychol Int 21(3):281–292

Juvonen J, Schacter H, Sainio M, Salmivalli C (2016) Can a school-wide bullying prevention program improve the plight of victims? Evidence for risk X intervention effects. J Consulting Clin Psychol 84:334–344

Keyes CLM, Ryff CD (1998) Generativity in adult lives: Social structural contours and quality of life consequences. Am Psychological Assoc 12:227–263

Keyes, CLM (1998). Social well-being. Social psychology quarterly, 121-140

Keyes, CLM, & Shapiro, AD (2001). Cumulative advantage in social well-being: Profiles by sex, age, and Socioeconomic index. Unpublished manuscript. Emory University

Lawler MJ, Newland LA, Giger JT, Roh S, Brockevelt BL (2017) Ecological, relationship-based model of children’s subjective well-being: Perspectives of 10-year-old children in the United States and 10 other countries. Child Indic Res 10:1–18

Lee BJ, Yoo MS (2015) Family, school, and community correlates of children’s subjective well-being: An international comparative study. Child Indic Res 8:151–175

Lereya ST, Samara M, Wolke D (2013) Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abus Negl 37(12):1091–1108

Leung CM, Ho MK, Bharwani AA, Cogo-Moreira H, Wang Y, Chow MS et al. (2022) Mental disorders following COVID-19 and other epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl, Psychiatry 12:205

Liu Y, Carney JV, Kim H, Hazler RJ, Guo X (2020) Victimization and students’ psychological well-being: The mediating roles of hope and school connectedness. Child Youth Serv Rev 108:104674

Lucas-Molina B, Perez-Albeniz A, Fonseca-Pedrero E (2018) The potential role of subjective wellbeing and gender in the relationship between bullying or cyberbullying and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res 270:595–601

Nickerson AB, Nagle RJ (2004) The influence of parent and peer attachments on life satisfaction in middle childhood and early adolescence. Soc Indic Res 66(1-2):35–60

OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD. (2023b). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris

Opdenakker MC, Van Damme J (2000) Effects of schools, teaching staff and classes on achievement and well-being in secondary education: Similarities and differences between school outcomes. Sch Effectiveness Sch Improvement 11(2):165–196

Painter, K (2014). USA is 12th, Panama 1st, in global well-being poll. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/09/16/global-well-being-poll-panama/15679637/

Pappa S, Chen J, Barnett J, Chang A, Dong RK, Xu W et al. (2022) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the mental health symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 76:41–50

Quintana-Orts C, Mérida-López S, Rey L, Extremera N (2021) A Closer Look at the Emotional Intelligence Construct: How Do Emotional Intelligence Facets Relate to Life Satisfaction in Students Involved in Bullying and Cyberbullying? Eur J Investig Health, Psychol Educ 11(3):711–725

Rask K, Astedt-Kurki P, Paavilainen EAdolescent Subjective Well-being and Family Dynamics. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 2003(2):129-138

Rivara, F, & Le Menestrel, S (Eds.). (2016). Preventing bullying through science, policy, and practice

Roberson AJ, Renshaw TL (2022) Dominance of general versus specific aspects of wellbeing on the Student Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. Sch Psychol 37(5):399–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000513

Rodríguez S, Valle A, Gironelli LM, Guerrero E, Regueiro B, Estévez I (2020) Performance and well-being of native and immigrant students. Comparative analysis based on PISA 2018. J Adolescence 85:96

Ruiz-Eugenio L, Roca-Campos E, León-Jiménez S, Ramis-Salas M (2020) Child well-being in times of confinement: the impact of dialogic literary gatherings transferred to homes. Front Psychol 11:567449

Ryff CD (1989) Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol 57(6):1069

Ryff CD, Keyes CLM (1995) The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Personal Soc Psychol 69(4):719

Ryff CD, Singer BH, Dienberg Love G (2004) Positive health: connecting well–being with biology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci 359(1449):1383–1394

Saarento S, Boulton AJ, Salmivalli C (2015) Reducing bullying and victimization: Student- and classroom-level mechanisms of change. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43:61–76

Sachs, JD, Layard, R, & Helliwell, JF (2018). World Happiness Report 2018 (No. id: 12761)

Savahl S, Montserrat C, Casas F, Adams S, Tiliouine H, Benninger E, Jackson K (2019) Children’s experiences of bullying victimization and the influence on their subjective well-being: A multinational comparison. Child Dev 90(2):414–431

Schnettler B, Miranda-Zapata E, Sánchez M, Orellana L, Lobos G, Adasme-Berríos C, Sepúlveda J, Hueche C (2021) Cross-cultural measurement invariance in the Satisfaction with Life Scale in Chilean and Spanish university students. Suma Psicol ógica 28(2):128–135

Seon Y, Smith‐Adcock S (2021) School belonging, self‐efficacy, and meaning in life as mediators of bullying victimization and subjective well‐being in adolescents. Psychol Sch 58(9):1753–1767

Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M (2020) The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM Int J,Med 113:531–537

Shin H, Park C (2022) Social support and psychological well-being in younger and older adults: The mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction. Front Psychol 13:1051968

Silișteanu SC, Totan M, Antonescu OR, Duică L, Antonescu E, Andrei Emanuel Silișteanu (2022) The Impact of COVID-19 on Behavior and Physical and Mental Health of Romanian College Students. Medicina 58(2):246

Soutter AK, O’Steen B, Gilmore A (2014) The student well-being model: a conceptual framework for the development of student well-being indicators. Int J Adolescence Youth 19:496–520

Steinmayr R, Crede J, McElvany N, Wirthwein L (2016) Subjective well-being, test anxiety, academic achievement: Testing for reciprocal effects. Front Psychol 6:146375

Stenlund S, Junttila N, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Sillanmäki L, Stenlund D, Suominen S, Rautava P (2021) Longitudinal stability and interrelations between health behavior and subjective well-being in a follow-up of nine years. PloS one 16(10):e0259280

Thakur V, Jain A (2020) COVID 2019-suicides: a global psychological pandemic. Brain Behav Immun 88:952–953

Tomé G, de Matos MG, Camacho I, Simes C, Diniz JA (2014) Friendships Quality and Classmates Support: How to influence the well-being of adolescents. High Educ Soc Sci 7(2):149–160

VanderWeele TJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (2012) On the reciprocal association between loneliness and subjective well-being. Am J Epidemiol 176(9):777–784

Varela JJ, Sirlopú D, Melipillán R, Espelage D, Green J, Guzmán J (2019) Exploring the Influence School Climate on the Relationship between School Violence and Adolescent Subjective Well-Being. Child Indic Res 12(6):2095–2110

Varela, JJ, Fábrega, J, Carrillo, G, Benavente, M, Alfaro, J, & Rodríguez, C (2020). Bullying and subjective well-being: A hierarchical socioeconomical status analysis of Chilean adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 118

Yubero S, de las Heras M, Navarro R, Larrañaga E (2023) Relations among chronic bullying victimization, subjective well-being and resilience in university students: a preliminary study. Curr Psychol: Res Rev 42(2):855–866

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (NO.1233300002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: Jian Li and Eryong. Xue.; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: Jian Li, Eryong. Xue, Wenrui, Zhou, Shuxuan, Guo and Yimei, Zheng; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Jian Li and Eryong. Xue; Final approval of the version to be published: Jian Li and Eryong. Xue.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as this article used published data.

Informed consent

This article applied the open access dataset and does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Xue, E., Zhou, W. et al. Students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparison between PISA 2018 and PISA 2022. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 16 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04340-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04340-3