Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the patterns of sick leave, as well as factors associated with sick leave due to COVID-19 during one year after the COVID-19 diagnosis, and sex-related aspects on sick leave. This nationwide study involved 11,902 individuals who received sickness benefits for COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. Data from three Swedish registries were analyzed for sick leave that commenced between March 1 and August 31, 2020, with a follow-up period of 12 months. Sick leave due to COVID-19 was counted as the number of days with sickness benefits and required to include at least one registered COVID-19 diagnosis. The median duration of sick leave was 35 days, and 347 (2.9%) individuals continued their sick leave during the entire follow-up period. Furthermore, 1 year later, the cumulative incidence of sick leave was slightly higher in males (3.5%) compared to females (2.7%). Older age, being single with no children, diagnosed with the virus, medium income level, history of sick leave, and need for inpatient care were significantly associated with a higher duration of sick leave due to COVID-19, both in the total population and when stratified by sex. These results indicated that three out of 100 (3%) patients were still on sick leave 1 year after their COVID-19 diagnosis. Aspects regarding the importance of sick leave duration differed between males and females and comprised sociodemographic characteristics and need for inpatient care. The results indicated the complexity of sick leave due to COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus posed a significant challenge for healthcare and the public system1. COVID-19 caused long-term consequences in many areas, including activity and participation limitation, psychological functioning, and manifestations in the central nervous, cardiovascular, and pulmonary systems1,2,3,4,5. Collectively, these negatively affect an individual’s health.

Sick leave is an indicator of poor self-reported health, mild psychiatric morbidity, long-term physical illness, disability, and mortality6. In Sweden, the employer pays for the first two weeks of sick leave. Thereafter, sickness benefits are paid by the tax-financed Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA). The SSIA is a public authority that administers financial compensation during sickness absence to those with all types of employment, on parental leave, or unemployed. The SSIA uses a model that becomes more stringent as absence from work increases. The SSIA granted 601,667 and 591,028 individuals (approximately 6% of the Swedish population) sickness benefits in 2018 and 2019, respectively7,8. However, during the first pandemic year, a sharp increase was observed as 680,000 people were granted sickness benefits in 20209.

We demonstrated that 9% of individuals who had taken sick leave due to COVID-19 (during the first wave in Sweden, spanning from March 1 to August 31), were still on sick leave at the end of a four-month follow-up10. In a large cohort of public employees, approximately one-third reported problems regarding work ability due to COVID-192. In addition, sex, old age, severe COVID-19 infection, and a prior history of sick leave were associated with COVID-19 related sick leave early after an infection10,11,12. However, the long-term consequences of COVID-19 on sick leave remain unclear.

Previous studies also reported that females were more likely to report a greater degree of disability during sub-acute and post COVID-192,13,14,15. Meanwhile, males were more likely to have more severe COVID-19 and require inpatient care2,13,14,15. In Sweden, sex differences were reported regarding the overall number of people who received sickness benefits, with a higher proportion among females7,8,9. Sex differences were related to sick leave duration during 1–24 weeks after COVID-19 infection16. Higher duration of sick leave was related to older age and severity of COVID-19 infection in females and males, respectively16. However, the additional factors that contribute to prolonged sick leave, as well as patterns of sick leave in a longer follow-up period after COVID-19 infection remain unclear.

This study aimed to investigate the patterns of sick leave, as well as factors associated with sick leave due to COVID-19 during one year after the COVID-19 diagnosis, and sex-related aspects on sick leave.

Methods

Study design and individuals

In this nationwide registry study, data from three Swedish registries were analyzed. The SSIA provided data on employment type, employment status, and sick leave 1 year prior to COVID-19, as well as the first year after the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Board of Health and Welfare provided data on date of death during the study period. Data from the National Patient Register, which includes all inpatient care in Sweden, were used to investigate hospital stay due to Covid-19. Statistics Sweden provided data on sociodemographic variables. A unique Swedish personal identification number was used to pool data. Data files were pseudonymized and contained serial numbers used to merge them. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare maintained the code key for the serial numbers.

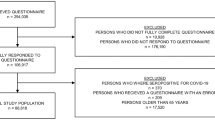

The inclusion criteria were residents of Sweden aged ≥ 18 years who received sickness benefits due to COVID-19 (defined according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes U 07.1 or 07.2). Sick leaves were required to have commenced between March 1 and August 31, 2020 (which corresponded to the first wave in Sweden), with a follow-up period of 12 months. Data were excluded if individuals had unspecified diagnoses (ICD codes Z, n = 27), died during the study period (n = 30), or had a primary diagnosis based on ICD codes that indicated diseases of uncertain etiology (n = 23).

Outcomes

The outcome was a count variable of the duration of sick leave due to COVID-19 as registered by the SSIA. When followed-up the sick leave period was required to include at least one sick leave due to a COVID-19 (confirmed by laboratory tests and assigned the ICD code U 07.1. If virus was not identified, the ICD code U 07.2 was assigned). However, it could be combined with sick leave due to other diagnoses if the gap between them was less than two weeks and the other diagnosis was deemed related to COVID-19. Such related diagnoses could include viral infections, fever, or a second sick leave registration due to COVID-19. The list of related diagnoses was provided by Westerlind et al.10 in the Supplementary Table 1. If the gap in non-registration between sick leave periods was ≤ 2 weeks, it was regarded as one period. In accordance with the Swedish social insurance regulations, work ability is primarily related to current employment status for up to 180 days of sick leave. From ≥ 181 days, it is related to the general labor market.

Explanatory variables

Sick leave prior to COVID-19 was defined as either being on sick leave for at least 28 days or at least six times between March 1, 2019, and the start of the study period (March 1, 2020).

Employment status at the start of sick leave due to COVID-19 was categorized as employment (which included on parental leave, combined employment), self-employment, or unemployment (which included those who studied).

In the year prior to COVID-19, educational level was categorized as primary school (≤ 9 years), secondary school (10–12 years), short university education (13–14 years), or long university education (≥ 15 years). In the regression analyses, the variable was dichotomized as had an education of ≤ 12 years or ≥ 13 years.

Income, in the year prior to COVID-19 (2019), was counted as each person’s disposable income in Swedish Krona (1 Euro = 9.94 SEK, October 29, 2021). To simplify the interpretation, the variable was analyzed in tertiles.

Countries of birth were categorized as Sweden, Nordic countries, except Sweden, European countries, except Nordic countries, or countries outside Europe. In the regression analyses, the variable was dichotomized as Sweden or all other countries.

Familial status, in the year of COVID-19 (2020), was presented as married (which comprised of both married and registered partnership) with children, married without children, single with children, or single without children.

Inpatient care due to COVID-19 was classified as more than 1 day of hospital stay with registration of COVID-19 (U07) as either the primary or secondary diagnosis10.

Statistics

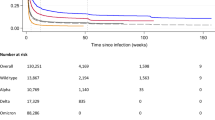

To investigate the patterns of sick leave, Kaplan–Meier curves were used to graphically present the cumulative incidence of sick leave over time. No censoring was applied.

Regression analysis

A regression analysis was performed to identify factors that explain the duration of sick leave. The outcome was a count variable: sick leave duration during the 1-year period after the first wave of COVID-19. Examination of the variable distribution revealed a small peak at 181 days, long tail ≥ 181 days, and another peak at 365 days at the end of the follow-up (Fig. 1). The peak observed at 181 days could be explained by the Swedish regulations, as described in the outcomes. The second peak at 365 days could be explained by the fact that the follow-up period finished at this time point. The regression model was fitted with the total data from 1 to 356 days.

Subgroup analyses were performed with data on sick leave durations of 1–180 days. We anticipated that having a single data point with such a pronounced peak might introduce noise into the model and potentially influence the model parameters. Simultaneously, our objective was to investigate the factors influencing sick leave duration during the 12 months following the initial COVID-19 diagnosis. Therefore, to mitigate potential noise and ensure a more focused analysis, we conducted a subgroup analysis specifically for the 1–180-day duration range.

The mean and variance were examined to select the proper regression analyses. The mean was less than the variance, indicating that negative binomial regression was a more suitable approach17. The explanatory variables were age, employment status, education/dichotomized, country of birth/dichotomized, familial status, COVID-19 diagnosis, and need for inpatient care. These explanatory variables were selected based on previous studies2,10,11,12,16,18. In addition, we conducted interaction analyses on the total sample to examine the potential moderating effects of sex on the relationship between each explanatory variable and the outcome. The identification of statistically significant interactions indicated that sex plays an important role in influencing how these explanatory variables relate to the outcome. Moreover, the models were stratified for both males and females.

Negative binomial regression analysis was performed to predict sick leave duration. To ensure the utmost robustness and reliability of our models, the dataset was randomly divided into two subsets: a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%). We wanted to access the model's proficiency in generalization and its capacity to provide precise predictions for unseen data. For the validation parameters, a simple bootstrapping method was chosen with n = 500 random resamples. The negative binomial regression model was fitted to the training data via the validation parameters. The trained model was evaluated regarding the root mean square error (RMSE) and R-squared values. The models were further fitted to the testing set and the values were evaluated. In addition, to investigate sex-related differences in the factors that explained the duration of sick leave, the effect of modifying sex on independent variables by including interaction terms in the regression models was investigated.

Dispersion parameter (SE) and Akaike information criteria (AIC) were reported for all regression models. Results at the variable level were evaluated using beta coefficients (β), 95% confidence intervals (CI) for OR, and p-values.

Missing data: The number (n) and percentage (%) of missing data per variable were reported. The observed percentage of missingness in regression models ranged from 0.5 to 1.5%. Hence, we made the decision not to impute data due to the low frequency of missing values.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY) and R software (R Core Team, version 4.0.2). The significance level for two-tailed tests was set at an alpha level of 5%.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020–03046, amendment 2020–03922). Collected data were protected by confidentiality regulations for Public Access to Information. Secrecy Act (2009:400), Chapter 24. The data were handled in accordance with the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Swedish law (2018:218), which supplemented the GDPR. The Declaration of Helsinki was not relevant to this project, which was based on data generated in public registries.

Informed consent

According to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, quality registers are exempt to the general rule of patient consent according to the Personal Data Act (Swedish law No. SFS 1998:204).

Results

Study population

The study population comprised 11,902 individuals (Table 1). The median age was 47.9 years, 40% were males, and 25% required inpatient care due to COVID-19.

Sick leave patterns during 12 months after COVID-19 onset

The median duration of sick leave due to COVID-19 was 35 days (mean [SD], 59.4 [70] days) (Table 1). Moreover, 347 (2.9%) individuals continued their sick leave during the entire follow-up period of 12 months (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the cumulative incidence was slightly higher in males (3.5%) compared to females (2.7%) (Fig. 2B).

Prediction of sick leave duration (range 1–365 days)

Odds for longer sick leave increased if individuals were self-employed (OR 1.09), unemployed (OR 1.19), older (OR 1.01 per gained year), single with no children (OR 1.08), single with children (OR 1.06), had been on sick leave before COVID-19 (OR 1.22), had an education of ≥ 13 years (OR 1.06), required inpatient care (OR 1.92), and of the female sex (OR 1.06) (Table 2). Moreover, the odds decreased for individuals born outside Sweden (OR, 0.94) and those without laboratory confirmed COVID-19 virus (ICD code, U 07.2 [OR, 0.85]).

Sex-related aspects in regarding sick leave duration (range 1–365 days)

Significant interactions were found between sex, age, country of birth, family status, type fo COVID-19 ICD-10 codes, income, education level, and inpatient care (Table 3). Country of birth outside Sweden, being single with or without children, having a high-income level, and an education of ≥ 13 years were significantly associated with longer sick leave duration in females; however, not in males (Table 3).

Subgroup analyses for predicting sick leave duration (1–180 days)

Odds of longer sick leave duration increased if individuals were self-employed (OR 1.13), older (OR 1.00 per gained year), single with no children (1.07), on sick leave before COVID-19 (OR 1.12), required inpatient care (OR 1.31), and of the female sex (OR 1.02). Moreover, the odds of longer sick leave duration decreased if individuals had a medium income level (OR 0.97) and for those without laboratory confirmed COVID-19 virus (ICD code, U07.2 [OR 0.90]) (Supplementary Table 1). Results of the interaction analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Discussion

In this Swedish nationwide registry study on sick leave during the first wave of the pandemic, people were on sick leave for a median of 5 weeks. Among the 11,902 individuals, 3% were still on sick leave after 12 months, with a slightly higher proportion among males. Moreover, sociodemographic characteristics, previous history of sick leave, and need for inpatient care due to COVID-19 were significantly associated with the duration of sick leave. These results reflected the multitude of factors that influenced sick leave and work capacity after COVID-19 and indicated the need for long-term follow-up19. In the present study, individuals with a longer duration of sick leave could have had a post COVID-19 condition, defined as symptoms that lasted for at least 12 weeks20. Therefore, person-centered rehabilitation might be necessary for people who have persistent symptoms and are unable to work.

The outcome of this study, sick leave durations from 1 to 365 days, revealed two peaks: one at 181 days and another towards the end of the study period. The first peak could be linked with the Swedish system regarding sick leave. According to Swedish sick leave regulations, till ≤ 180 days of sick leave, work ability was related to present employment. From ≥ 180 days, it was related to the general labor market. The second peak at 365 days corresponded to the termination of our study's follow-up period.

In the present study, individuals were more likely to have a longer sick leave duration if they were female, older, self-employed or unemployed, single (with or without children), or had a history of sick leave prior to COVID-19. However, individuals were less likely to have a longer sick leave duration if they did not require inpatient care, were born outside Sweden, or had a non-detected SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (ICD code: U07.2). Generally, sick leave was more common among females than among males in the Swedish population, which was also reported in COVID-19 cohorts7,8,9,21. While females were more likely to report a greater degree of disability during the subacute and post-acute phases of COVID-19, males were more likely to have more severe COVID-19 and a greater requirement for inpatient care2,13,14. Individuals born outside of Sweden had a reduced likelihood of experiencing extended sick leave during the COVID-19 pandemic. While our regression model did not directly consider the birthplace's specific origin, our results parallel those found in the study by Spets et al.22. This implies that the country of birth, especially in the context of low-income countries, could exert a substantial influence on the duration of sick leave. Potential explanations for these findings could be the fear of losing employment or a pressing need to provide economic support to one's family23. Our findings could be interpreted regarding studies on sick leave due to other conditions and show the different aspects of importance in returning to work for females and males24.

In the presented study, older age was also found to predict longer sick leave duration in all analyses. However, the true effect of age was unclear. Older age was related to long-term sick leave owing to COVID-1918. However, previous findings suggested that a longer duration of sick leave was related to older age and severity of COVID-19 infection in females and males, respectively16. When interpreting the results of the present and previous studies, it must be considered that older males are more likely to develop severe COVID-19 and require inpatient care14,25.

In the total sample, as well as in the subgroup of males and females, not having detected SARS-CoV-2 virus was associated with lower odds for long sick leave duration. It could be speculated that individuals without detected virus had a less severe infection, as previous findings reported differences in self-reported symptoms after COVID-19 diagnosis based on the positive laboratory SARS-CoV-2 test26. However, these speculations should be handled cautiously as there was a shortage of test material in primary care during the first wave of the pandemic in Sweden, which led to U07.2 as a common diagnosis. It was possible that sick leaves were underestimated in this study. In this cohort, we previously showed that recurrent sick leave was present in 2.0% individuals within the first four months of sick leave (10). This may indicate that the number of people with longer sick leave due to COVID-19 may be higher than that in the present study.

Data from individuals who died during the first four months were not analyzed, which indicated that individuals with the most severe outcomes due to COVID-19 may not have been covered. The negative binomial regression models were fitted using a machine learning approach for two primary reasons. First, these models have the potential to generalize to new, unseen data, which is crucial in predicting outcomes across various populations. Second, machine learning models offer the advantage of being regularly updated as new data becomes available. This capability allows for the integration of the latest information and trends, a feature particularly vital in the rapidly changing landscape of a pandemic.

A limitation of this study was that we had no information on deaths beyond the first four months of follow-up. However, this large nationwide cohort constituted robust data with a presumed representative sample given its size and coverage. These results should be interpreted in relation to the Swedish context as the availability of paid sick leave may differ between countries27,28,29,30. Another limitation was that some variables that may be relevant when analyzing sick leave were lacking. We did not have information on the initial COVID-19 severity. However, information on the need for inpatient care was used as a proxy for COVID-19 severity. In addition, information on the type of work, work demands, and tasks was unavailable. However, we used employment types that provided work-related information to explain the sick leave duration. Nevertheless, this study lacked information on variables that may have contributed to explaining sick leave duration31.

Conclusions

The results of this nationwide registry-based study indicated that three out of 100 individuals were still on sick leave one year after their COVID-19 diagnosis. Aspects of the importance of sick leave duration differed between males and females and comprised sociodemographic characteristics and the need for inpatient care. This indicated the complexity of sick leave due to COVID-19. These results indicate the need for long-term follow-ups to identify people who might benefit from targeted vocational rehabilitation.

Data availability

Due to the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, open access cannot be provided. Requests to access the dataset can be submitted from qualified researchers to the authors. According to the Swedish regulation http://www.epn.se/en/start/regulations/, data can only be used in accordance with the application for this study that was approved by the Ethical board.

References

Levine, R. L. Addressing the long-term effects of COVID-19. JAMA 328, 823–824. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.14089 (2022).

Kröönström, L. A., Krause, J., Larsson, S. B., Sigström, R. & Sunnerhagen, K. S. Long-term self-reported health and disability after COVID-19 in public employees. BMC Public Health 22, 2400. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14820-3 (2022).

Higgins, V., Sohaei, D., Diamandis, E. P. & Prassas, I. COVID-19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 58, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895 (2021).

Bourmistrova, N. W., Solomon, T., Braude, P., Strawbridge, R. & Carter, B. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.031 (2022).

Badinlou, F., Forsström, D., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Abzhandadze, T. & Lundgren, T. Impairments following COVID-19 infection: Manifestations and investigations of related factors. Sci. Rep. 13, 6564. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33810-y (2023).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Sickness absence as a global measure of health: Evidence from mortality in the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 327, 364. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7411.364 (2003).

Försäkringskassan (Swedish Social Insurance Agency). Social Insurance in Figures 2019 1–70 (2019). SBN: 978-91-7500-407-5

Försäkringskassan (Swedish Social Insurance Agency). Social Insurance in Figures 2020 1–70 (2020). ISBN: 978-91-7500-406-8

Försäkringskassan (Swedish Social Insurance Agency). Social Insurance in Figures 2021 1–86 (2021). ISBN: 978-91-7500-406-8

Westerlind, E., Palstam, A., Sunnerhagen, K. S. & Persson, H. C. Patterns and predictors of sick leave after Covid-19 and long Covid in a national Swedish cohort. BMC Public Health 21, 1023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11013-2 (2021).

Palstam, A., Westerlind, E., Sunnerhagen, K. S. & Persson, H. C. Recurrent sick leave after COVID-19: Investigating the first wave of the pandemic in a comprehensive Swedish registry-based study. BMC Public Health 21, 1914. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11918-y (2021).

Abzhandadze, T., Westerlind, E. & Persson, H. C. Impact of pre-pandemic sick leave diagnoses on the length of COVID-19-related sick leave: A nationwide registry-based study. BMC Public Health 23, 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15115-x (2023).

Vahidy, F. S. et al. Sex differences in susceptibility, severity, and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019: Cross-sectional analysis from a diverse US metropolitan area. PLoS One 16, e0245556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245556 (2021).

Weizman, O. et al. Machine learning-based scoring system to predict in-hospital outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 115, 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2022.08.003 (2022).

Jin, J. M. et al. Gender differences in patients With COVID-19: Focus on severity and mortality. Front. Public Health 8, 152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 (2020).

Skyrud, K., Telle, K. & Magnusson, K. Impacts of mild and severe COVID-19 on sick leave. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 1745–1747. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab182 (2021).

Cameron, A. C. & Trivedi, P. K. Regression Analysis of Count Data (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Jacob, L. et al. Prevalence of, and factors associated with, long-term COVID-19 sick leave in working-age patients followed in general practices in Germany. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 109, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.06.063 (2021).

Ose, S. O. et al. Follow-up regimes for sick-listed employees: A comparison of nine north-western European countries. Health Policy 126, 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.05.002 (2022).

Soriano, J. B., Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P. & Diaz, J. V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, e102–e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00703-9 (2022).

Kisiel, M. A. et al. Patterns and predictors of sick leave among Swedish non-hospitalized healthcare and residential care workers with Covid-19 during the early phase of the pandemic. PLoS One 16, e0260652. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260652 (2021).

Spetz, M. et al. The sociodemographic patterning of sick leave and determinants of longer sick leave after mild and severe COVID-19: A nationwide register-based study in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 191. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad191 (2023).

Fassani, F. & Mazza, J. A vulnerable workforce: Migrant workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. (Publications Office of the European Union Luxembourg, 2020).

Palstam, A., Westerlind, E., Persson, H. C. & Sunnerhagen, K. S. Work-related predictors for return to work after stroke. Acta Neurol. Scand. 139, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13067 (2019).

Arnold, C. G., Libby, A., Vest, A., Hopkinson, A. & Monte, A. A. Immune mechanisms associated with sex-based differences in severe COVID-19 clinical outcomes. Biol. Sex Differ. 13, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-022-00417-3 (2022).

Matta, J. et al. Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 182, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454 (2022).

Heymann, J. et al. Protecting health during COVID-19 and beyond: A global examination of paid sick leave design in 193 countries. Glob. Public Health 15, 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1764076 (2020).

Hanage, W. P. et al. COVID-19: US federal accountability for entry, spread, and inequities—lessons for the future. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00689-2 (2020).

Sommers, B. D. & Coburn, B. E. Prescribing paid sick leave—an important tool for primary care during the pandemic. JAMA 324, 324–325. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12209 (2020).

Pollack, C. C. et al. The impact of state paid sick leave policies on weekday workplace mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.08.019 (2022).

Smallwood, N., Harrex, W., Rees, M., Willis, K. & Bennett, C. M. COVID-19 infection and the broader impacts of the pandemic on healthcare workers. Respirology 27, 6 (2022).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. The Swedish state under an agreement between the Swedish government and county councils [Grant numbers: ALFGBG-942914, ALFGBG-965653, ALFGBG-983604], Forte/Formas [Grant number: 2020–02775], regional research funding for the Vastragotaland region [Grant numbers: VGFOUREG-940508 and VGFOUREG-969267], and AFA Insurance [Grant number 200324]. The design and results of this study were completely independent of any influence or impact from the grant providers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception and design: T.A., E.W., A.P., K.S.S., and H.C.P.; acquisition of data: E.W., A.P., K.S.S., and H.C.P.; data analysis: T.A.; interpretation of data: T.A., E.W., A.P., K.S.S., and H.C.P.; drafting of the article: T.A.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: E.W., A.P., K.S.S., and H.C.P. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abzhandadze, T., Westerlind, E., Palstam, A. et al. Sick leave one year after COVID-19 infection: a nationwide cohort study during the first wave in Sweden. Sci Rep 14, 572 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50413-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50413-9

This article is cited by

-

COVID-19 infection and later risk of sickness absence by socioeconomic status: a cohort study

BMC Public Health (2024)