Abstract

Background

Management of the COVID-19 pandemic has been plagued by an online ‘infodemic’, not least on the topic of vaccine safety. Failure to vaccinate is often addressed with corrective, factually based information. However, this may be overly simplistic. European vaccine hesitancy levels correlate closely with popularity of populist parties while scientific populism refers specifically to populist distrust in scientific expertise.

Aims and method

Combining an evaluation of risk through the health belief model and the cognitive constructs from the theory of planned behaviour, with the influence of populist statements, anticipated regret, trust, and past healthcare behaviour, an online survey explored the components of vaccine decisions amongst a demographically representative Irish adult sample (N = 1995).

Results

The regression model accounted for a large proportion of variance amongst the total sample. A primary set of influences suggests a considered risk evaluative decision-making approach while a second tier of weaker influences incorporates a broader set of values beyond cost–benefit analysis. Six ideological subsets were identified through K-means analysis. Segments were differentiated by subjective norms attitudes (particularly around social media), populist political attitudes, self-efficacy, perceptions of COVID-19 severity, and susceptibility to the condition.

Conclusions

While the ‘right thing to do’ is clear when viewed through a lens of scientific expert advice, this is precisely the paradigm which populist movement rejects. Segmentations, such as the outputs from this study, validate the importance of proactively engaging with diverse communities both on and offline and afford a framework for developing and evaluating more refined, targeted, policies and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effects of the coronavirus disease first identified in Wuhan, China, known as COVID-19, continue to impact socially and economically across the globe. There is no specific treatment. Vaccinations are considered a key weapon in slowing the spread of COVID 19 and weakening its impact on those affected by it. Management of the COVID-19 pandemic has been plagued by a concurrent online ‘infodemic’ of misinformation, not least on the topic of vaccine safety [1].

Despite vaccination programme successes, vaccination participation has declined sharply in recent years across the wealthy developed world [2, 3]. Known as ‘vaccination hesitance’, the initial trigger to public mistrust for vaccines is often traced back to a discredited source, for example, a 1998 article claiming a link between the MMR jab and conditions including late-onset autism [4]. Childhood immunisation programmes like MMR might also be said to be victims of their own success in that the near eradication of disease has eroded social memory of the importance of vaccination for proactive preventative care [5]. Other negative press, for example, mandatory vaccination for USA healthcare workers during the 2009 Swine Flu pandemic [6] and, closer to home, adverse reaction cases from the same pandemic being settled in the Irish high court currently [7], has further bolstered vaccine mistrust.

Similar to patterns tracked in USA data [8], vaccine uptake rate intentions in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) dropped from an initial 65% in March [9] to 54–56% in September [10, 11] to 53% in October [12], with an upward trend towards 75% claiming they intended to accept a vaccine in January 2021 [13]. The current study aimed to identify subsets within a sample of adults living in Ireland based on their responses to a survey linking to populist political beliefs, established health models that explain behavioural intentions (health belief model [HBM], theory of planned behaviour [TPB] and other facilitators or barriers to vaccine uptake intentions.

HBM

In examination of key drivers behind vaccine attitudes, HBM is a helpful risk evaluation model for health behaviour decisions [14]. This model outlines a cost/benefit analysis of decision-making, weighing up such factors as perceived susceptibility to a condition, its perceived severity, and perception of how effective the health behaviour (in this case vaccination) is likely to be, as well as behaviour prompts to action (cues) and perceived barriers. Consistent with the HBM risk evaluative model, higher levels of perceived susceptibility to the condition [15] and worry and engagement with media content about COVID-19 [16, 17] have been found to correlate positively with health-protective behavioural intentions.

Within such a rational decision-making framework, failure to vaccinate is often assumed to represent either a cynical radical fringe or a misunderstanding of risk profile [2, 18] and thus is often addressed with corrective, factually based information [19]. However, this may be an overly simplistic assumption. For example, in the context of increasingly individualistic versus communal social values [20], a person’s choice to eschew public health advice and benefit from social herd immunity to a disease, while avoiding potential vaccine side effects, considered from an individualist perspective, in fact, represents an entirely logical choice [19]. Thus, the current study builds on the rational components within the HBM, by adding Ajzen’s [21] TPB framework to tease out decision-making processes in relation to vaccination acceptance, via a comprehensive three-factor model where three cognitive constructs (1. ‘attitudes’ to the behaviour in question, 2. perceptions of ‘subjective (social) norms (SN)’ and 3. an ability ‘perceived behavioural control’ (PBC) factor) are conceptualised as direct determinants of behavioural intention, the predecessor to action.

TPB

Within the TPB framework, ‘attitudes’ refer to a general assessment of the favourability of the ‘perceived consequences of a behaviour’ [22] and may arise out of both instrumental and affective outcome evaluations [22] with ‘good–bad’ an example of instrumental evaluation of the behaviour’s utility while ‘enjoyable–unenjoyable’ elicits respondents’ anticipated affective experience. SN is a measure of perceived social pressure to perform the behaviour and is derived from beliefs held about specific individuals and groups [23]. In the context of a vaccine for COVID-19 significant referents might include friends, family, healthcare professionals, social media, and mainstream media influences. PBC covers both a direct agentic competence, somewhat akin to self-efficacy [24] and indirect external factors beyond personal control [23]. While higher self-efficacy is usually associated with proactive behaviour, inverse relationships with vaccine intentions have also been found [25].

TPB has been successfully used to explore and explain vaccine intentions across diverse populations and contexts: H1N1 amongst students [25], HPV amongst students [26], future HIV vaccination [27], and parental decision-making for children’s vaccination [28].

Expanding beyond health explanatory models

While countries worldwide have instituted stay-at-home orders, today’s global citizen travels widely on internet ‘space’ directed by algorithms [29] to sites often largely or entirely divorced from local physical or community ‘place’ [20, 30]. Individuals who question vaccine choices are proactive and energetic researchers [17, 29, 31] with an extensive range of potential social influences.

Analysis of online space has found vaccine-hesitant clusters to be closely entangled with diverse and interlinked anti-vaccine and conspiracy clusters, where a proliferation of narratives offers something to suit every palate [29]. Meanwhile, pro-vaccine clusters are isolated in social media space [18], rendered less ‘sticky’ by their dry facts and figures message [32]. With vaccine perceptions influenced by such diverse factors as past health behaviours, individual knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, social networks, messages about vaccine safety, communication environment, cultural and religious influences, organization of health services, and expectations created by political leaders [33], it seems pro-vaccine messaging would do well to adapt a more nuanced approach to be more relevant to those researching vaccination online. Rather than generic, one-size-fits-all vaccine communications, segmentation may offer a means to identify meaningful sub-sets within the vaccine-hesitant population, allowing more nuanced pro-vaccine messaging to be developed with specific targets in mind [17, 34].

Segmentation teases out attitudes and motivations so that subsets, who share common features which differentiate them from the rest of the population, may be identified and targeted with messaging that directly addresses that segment’s combination of vaccination triggers and barriers.

For example, the anger activism model categorises attitudes to an issue in terms of their levels of both anger and efficacy, yielding empowered (low anger/high efficacy), activist (high anger/high efficacy), disinterested (low anger/low efficacy), and angry (high anger/low efficacy) groups [35, 36]. Ramanadhan et al. [17] segmented vaccine-hesitant American adults into hesitant sub-cohorts, distinguished by knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. At the furthest extreme, ‘disengaged skeptics’ were the least open to accepting a vaccine, while both the ‘informed but the unconvinced’ cohorts and the ‘open to persuasion’ group showed potential to re-appraise their vaccine positions. Analysis [37] of 44 variables within the March 2019 Eurobarometer survey identified 14 influential components that explained 66% of variance, yielding a 7-cluster solution, with a large pro-vaccination segment comprising of over half the sample, and 6 smaller clusters defined by level of hesitance, and motivations. The authors [37] note that the more nuanced understanding of hesitance motivations facilitated by such an approach has potential to overcome the polarising effects of simplistic pro versus anti-vaccine categorisations.

Spanning the traditional political left versus right spectrum, populism refers to a contemporary political ideology characterised by a dualistic narrative that prioritises the wisdom and wishes of a general ‘people’ in opposition to a supposedly corrupt elite [38]. This Manichean reification of ‘people’ and ‘elite’ is at odds with traditional democratic emphasis on the rights and agency of diverse cohorts and individual voters. The relative shallowness of populism’s ‘imagined community’ thesis allows it to thrive in the unbounded online space, aligning easily with such diverse ideologies as unsubstantiated alternative healthcare, nationalist and ethnic discourses, libertarianism, conservatism, ecologism, socialism, and other ideological narratives [38]. Scientific populism refers to a distrust by laypeople in scientific expertise, with climate change denial being one example, as would vaccine hesitancy be another. Populism’s elite versus people dichotomy has been operationalised [39] across three pillars: people-centrism and anti-elitism, the antagonistic relationship between the people and the elite, and a focus on the general will, together with a measure of political trust. Levels of national vaccine hesitancy have been found to correlate closely with popularity of populist parties (more than 70% of variance explained across measures) across 14 countries in Western Europe, including Ireland [2]. Thus, the role of populist attitudes in vaccine decision processes also deserves closer attention.

In addition, the HBM has been usefully supplemented with trust measures such as trust in doctor and trust in institutions (for example [40, 41]; see also Table 1) which is also the aim of the current study with the inclusion of HBM alongside populism and associated levels of layperson distrust of those in authority.

Anticipatory emotions, especially anticipatory regret, have been found to be a relevant component of vaccine decisions alongside the health belief model [41, 42] and across extensive health contexts with the theory of planned behaviour [43, 44]. More specifically, the current study examines the influence of future-focused anticipated regret (AR) that ‘enriches expectations with affect’ [44] which allows for a deeper and personal meaning than a purely rational calculation might give, especially as vaccination acceptance can be an emotive issue.

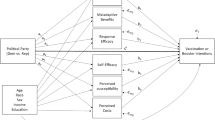

Combining an evaluation of risk through HBM and the cognitive constructs from the TPB model, together with agreement with populist statements, and both trust and associated past behaviour, and anticipated regret, a survey was developed to explore the components of vaccine decisions in an Irish context (see Fig. 1). The full survey is attached as Appendix.

The primary aim of the study was to build on existing knowledge of vaccine decision-making to understand the drivers of vaccine decision making specifically around COVID-19. Additionally, the research sought to differentiate between vaccine decision typologies, teasing out decision-making criteria across different segments. Ultimately, it was hoped that the research would enable distinct attitudinal cohorts to be identified and effectively targeted with persuasive, relevant messaging around accepting a vaccine for COVID-19.

Hypothesis

The research tested the hypothesis that a combination of the variables tested would explain a substantial proportion of the variance in Irish vaccine intentions (hypothesis 1), with the null hypothesis that the components tested would not explain substantial variance in Irish vaccine intentions. A second hypothesis posited that distinct communities or ideological subsets would be identifiable within the Irish population (hypothesis 2). The null hypothesis for hypothesis 2 was that segments based on the survey components would fail to deliver distinct intentional segments. The combined objective for the research was to identify those hesitant segments most amenable to change, and any topics more relevant to them.

The segments are also examined in relation to any possible gender differences. A meta-analysis of decision-making determinants in pandemic health behaviours [15] identified mixed outcomes based on demographic comparisons while correlations have emerged for more recent COVID-19-specific studies; for example, women may be more likely to accept a vaccine as they see the pandemic as a serious threat to health [45] and age; for example, older age groups may be more likely to accept a vaccine [46].

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited and took part anonymously via an online panel provider. Participants were individuals who had proactively signed up to an online panel provider. Typically panel members are invited by the panel to earn small incentive amounts for completing surveys for third party commissioning clients such as market research organisations, and other parties.

Responses were pseudo-anonymised such that each respondent was identified in the dataset by only a panel id with only the research organisation having access to survey responses. The panel provider had access to respondent name and identifying details, but no access to the survey responses.

The panel provider and research organisation were bound by a code of conduct [47] and reviewed the questionnaire to ensure that it met with industry standards in protecting the rights of the data subject.

Broad quotas were applied during the initial stages of fieldwork to ensure a sample demographically like the ROI population at Census 2016 in terms of age and gender. Some regional quotas were set; however, the final sample was skewed towards the Leinster region. Sample demographic characteristics are outlined in Table 2. Data collection took place between 15th October and 18th November 2020. After incomplete entries were removed from the originally received 2007 questionnaires, the final sample size for analysis was 1,995.

Design

The study was correlational in design. The criterion variable was the overall intentions to accept a vaccination for COVID-19. HBM predictor variables were perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, vaccine barriers, vaccine cues, and expected efficacy. TPB predictor variables were instrumental attitudes, affective attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy. Populism predictor variables were will of the people, anti-elite, antagonism between people and elite, and political trust. Past healthcare behaviour, trust, and anticipated regret are also included as predictors of overall intentions to accept a vaccination for COVID-19.

Materials

Overall intentions

Three intention question items, which had good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.86), contributed to an overall intention criterion score as follows:

-

1.

Would you accept a COVID-19 vaccine for yourself? (3-point scale—yes, maybe, no). Intention #1 was included as a replication of intention measure used in March 2020 [9].

-

2.

How likely, or unlikely would you be to take the first publicly available EU-approved COVID-19 vaccine? (5-point scale—very likely, fairly likely, not particularly likely, not at all likely, unsure/don’t know). Intention #2 was a repeat of a September 2020 wording [11].

-

3.

I will take a vaccine for COVID-19 when one is offered to me (5-point scale—agree strongly to disagree strongly). Intention #3 was developed as a generic alternative intentions wording.

In considering the TACT (time, action, context, target) model [22], time was left unspecified in the repeated measure intention question [9] while the other repeated measure refers to ‘the first publicly available EU-approved COVID-19 vaccine’. Lastly, a new measure was included which refers to ‘when one [vaccine] is offered to me’. The action was specified as accepting a vaccine for COVID-19 (context), and the target was identified in the survey introduction as the respondent themselves. A fifteen-point weighting system was designed to account for the different Intention scales (3-point scale: no = 5, maybe = 10, yes = 15, and 5-point = not at all likely/strongly disagree = 3, not particularly likely = 6, etc.). The combined overall intention scores fall between 11 and 45.

HBM

HBM likelihood variables included perceived susceptibility (I believe I am at risk of contracting COVID-19) (α = 0.62), barriers to the behaviour in question (I have negative feelings about accepting a vaccine for COVID-19) (α = 0.80), cues to the behaviour (I will have no difficulty accessing a vaccine when one is approved) (α = 0.47; cues to action items are examined separately due to this poor internal consistency reliability rating), perceptions around efficacy (I expect vaccination will prevent the spread of COVID-19) (α = 0.88), and severity (I would be at risk of complications if I were to contract COVID-19) (α = 0.71). All were answered using a 5-point Likert scale from disagree strongly (1), disagree somewhat (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree somewhat (4), and agree strongly (5). Principal components factor analysis was run on constructs with 3 or more items (the minimum for identification of a factor) with severity (the only HBM construct to comprise of three measures) loading on a single factor.

TPB

A short-form TPB was designed addressing the direct determinants for attitudinal and PBC constructs while the subjective norm variable has both direct and indirect items. TPB predictors included both an internal PBC construct (If I want to accept a vaccine for COVID-19 I will be able to do so), and external PBC (the vaccine will be easily accessible if I wish to accept it) (these items are examined separately due to this poor internal consistency reliability rating for overall self-efficacy; α = 0.50). Instrumental (α = 0.93) and affective (α = 0.79) attitudes were asked along a bi-polar 7-point Likert scale—e.g. pleasant/unpleasant, good/bad, and dangerous/safe. A mix of left–right and right-left positivity was used, and weightings were adjusted to account for this so that positive pole, regardless of side, was weighted as 7, and negative pole (whether right or left) was rated as 1. A set of injunctive subjective norm items (α = 0.88) covered close friends, family, healthcare professionals (HCP), mainstream media, and social media e.g. my doctor would recommend that I accept a vaccine for COVID-19, along with a general ‘people I respect’ item, and respondents also rated the importance of each specific influence out of 5 (not at all important (1)—very important (5)).

Principal component factor analysis identified 2 factors within the subjective norms measures. A first factor, denoted as subjective norms (SN), comprised of people I respect, close friends, family, HCP, and doctor while social media and traditional media items were loaded to a second factor, titled social norms (SocN).

Populism and political trust

Populist and trust questions [39] were comprised of 6 populism questions, two for each of the three dimensions (will of the people, α = 0.63; People versus the elite, α = 0.62; antagonism to elite, α = 0.68) e.g. ‘politicians in the Irish government need to follow the will of the people’. Responses ranged along a 5-point Likert scale from totally disagree (1), to totally agree (5), with interim values not named. The political trust question set (α = 0.95) was adapted slightly for an Irish content (e.g. indicate how much trust you have in the lower/upper house was reworded to refer to ‘the dail’/ ‘the seanad’, respectively). Responses ranged from 0 (no trust at all) to 10 (complete trust). Principal component analysis found political trust loaded as a single factor, as did the 6 popoulism questions combined, however populism subscales could not be tested as there are fewer than 3 items for each.

Past healthcare behaviour, HCP trust, and anticipated regret

Six questions, two for each predictor variable, were used to operationalise past healthcare behaviour (α = 0.90) (e.g. I tend to follow the advice of my doctor), trust (α = 0.90) (I trust the advice of HCP in relation to COVID-19), and anticipated regret (α = 0.83) (e.g. I would regret it if a vaccine was offered to me, and I did not take it [48].

Demographic questions

In addition to age, gender, and overall region, questions were included to capture county of residence, employment status, level of education attained, social class and presence, and age of children.

Results

This section will present firstly a descriptive summary of the data at a total level (see Table 3), including reliability statistics, and then present the findings from a regression analysis that measured relative contribution for predictor variables to the criterion overall intentions (hypothesis 1). Lastly, the results from the segmentation analysis (hypothesis 2) will be presented.

The descriptive statistics indicate moderately high levels of overall intentions, past behaviour (following HP instructions), trust (trusting HPs), anticipated regret, susceptibility, barriers, cues, efficacy expectations, perceived severity, affective attitudes, instrumental attitudes, self-efficacy, subjective norms populism, and political trust (see Table 3). In terms of subjective norm-specific sources, on average, the respondents indicated that their doctor and healthcare experts were the most important sources when making decisions to accept a vaccine for COVID-19 (see Table 4).

Inferential statistics—hypothesis 1

A hierarchical linear regression was used to test whether the health belief model (HBM) variables (model 1), the HBM plus theory of planned behaviour variables (TPB) (model 2), and the HBM and TPB plus the rest of the predictors (model 3), significantly predicted vaccination intentions. The results of the regression indicated that each model significantly explained variance (model 1: 60.6%; model 2: 71.8%; model 3: 74.5%) in overall vaccination intentions (model 1: R2 = 0.78, F(6, 1988) = 512.39, p < 0.001; model 2: R2 = 0.85, F(12, 1982) = 423.47, p < 0.001; model 3: R2 = 0.87, F(19, 1975) = 307.81, p < 0.001), with significant increases in variance explained between model 1 and model 2 (R2 change = 0.11/11%), and model 2 and model 3 (R2 change = 0.03/3%) (see Table 5).

It was found that anticipated regret significantly predicted vaccination intentions (model 3: β = 0.29, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.38–0.50), as did instrumental attitudes (model 2: β = 0.32, p < 0.01, 95% CI = 0.34–0.47; model 3: β = 0.25, p < 0.01, 95% CI = 0.25–0.38), barriers (model 1: β = − 0.54, p < 0.01, 95% CI = − 2.47 – − 2.20; model 2: β = − 0.28, p < 0.01, 95% CI = − 1.36 − − 1.08; model 3: β = − 0.23, p < 0.01, 95% CI = − 1.15 − − 0.87), subjective norms (model 2: β = 0.22, p < 0.01, 95% CI = 0.14–0.20). Some of other predictors did have significant relationships with vaccination intentions but their beta values were below 0.2 (see Table 5). Positive relationships occurred between anticipated regret/ instrumental attitudes/subjective norms and overall vaccination intentions, greater levels in the predictors linking to greater intentions to accept the vaccine if offered while greater levels of perceived barriers linked to lower intentions (negative relationship).

Inferential statistics—hypothesis 2

K-Means clustering (squared Euclidean distance iterative partitioning) set to analyse up to ten clusters, was conducted amongst the total sample (n = 1995). K-Means analysis was conducted using the Sphinx IQ analysis programme. Individuals were classified based on mean scores for susceptibility to COVID-19, trust in HCP, illness severity, vaccine effectiveness, past health behaviour, barriers, anticipated regret, subjective norms, affective attitudes, and instrumental attitudes. Given that their relationship with the rest of the variables was hypothesised only, political trust and populism variables were omitted from the cluster analysis. The individual cues and efficacy variables were also excluded, on the basis that ordinal variables are not appropriate for K-means analysis.

A six-cluster solution was chosen as providing a satisfactory level of discrimination within both pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine segments, with minimal ratio of gains and discriminating power to be achieved from adding additional clusters (see Table 6). The segmentation was run repeatedly, with the same variables, and the segmentation was deemed robust when consistent classes were observed to emerge each time the analysis was run.

As outlined in Table 7, t-tests identified clear differences between the groups. Two of the six cluster groupings (A and B) expressed above-average vaccine uptake intentions, while the remaining four (C, D, E, and F) expressed below-average vaccine uptake intentions (see Fig. 2).

Segment A (‘wholehearted’: 25%) expressed the highest vaccine intentions, and this cohort over-indexed on almost all measures, except two, namely, vaccine barriers (reverse score), which they under-indexed significantly on, and the political constructs. Segment A under-indexed on the populist anti-elitism dimension and did not differ from the mean on the other two populism constructs, although they expressed above-average political trust (See Table 7).

Segment B (‘discerning proponents’: 21%) also expressed above-average vaccine intentions. Like segment A, they over-indexed for most attitudinal scores, except the reverse-scored barriers, on which they under-indexed significantly. Their agreement with SocN statements did not differ significantly from the mean. They also did not differ from the mean on the internal ability statement ‘it is up to me whether I accept a vaccine for COVID-19’. Like segment A, segment B expressed high political trust. However, this group registered lower than average agreement with the populism ‘will of the people’ construct with average levels of agreement for the other populist constructs (See Table 7).

Segment C (‘on the fence’: 16%) registered slightly below-average intentions. They expressed above-average agreement with vaccine barriers and did not deviate from the mean in their perceptions of either expected disease severity or vaccine efficacy, nor the cues statement ‘I have heard good things about the development of a vaccine. This segment scored below the mean for anticipated regret, both instrumental and affective attitudes, the external ability statement ‘if I want to accept a vaccine for COVID-19 I will be able to do so’ and for SN, and SocN. Political variables did not emerge as differentiators for this cohort as they did not differ from the mean for political trust, nor any of the populism constructs (See Table 7).

Segment E (‘worried sceptics’: 15%) registered a similar, marginally lower, level of vaccine intentions as segment C. In common with segment C, they over-indexed for barrier statements, and under-indexed on anticipated regret, and both affective and instrumental attitudes. However, in contrast with segment C, segment E over-weighted illness severity perceptions and did not differ from the mean for susceptibility to COVID-19, nor for any cues or ability statement. They expressed lower than average past health behaviour, trust in HCP, and above-average SN and SocN sentiments. While not diverging from the mean for political trust, this cluster expressed above-average agreement with the populist anti-elite and antagonism towards the elite dimensions (see Table 7).

Segment D (‘disengaged cynics’: 18%) expressed the second-lowest intentions. Apart from the reverse weighted barriers construct, which they over-indexed on, and populist constructs, this cohort registered below-average agreement levels almost across the board. They expressed below-average political trust but did not differ from the mean for populist constructs (see Table 7).

Segment F (‘emphatic rejectors’: 5%), the smallest cohort of the total, expressed the lowest vaccine intentions by a significant margin. In common with segment D, this group also registered below-average agreement levels for attitude statements except the reverse weighted barriers construct for which they over-indexed. Like segment D, they also registered lower than average political trust. However, in contrast to segment D, segment F registered an above-average agreement with all three populism dimensions. In common with segment A (‘wholehearted’), this cluster expressed above-average agreement with the internal efficacy statement ‘It is up to me whether I accept a vaccine for COVID-19’ (see Table 7).

To examine demographic factor influences gender and age influences were examined. A chi-square cross-tabulation test showed that the association between gender and segment membership was not statistically significant (χ2(10) = 14.21, p = 0.16), suggesting that segment membership did not noticeably vary across the gender groupings (see Table 8).

‘Emphatic rejectors’ (F) are in the minority across all age groups, with an even smaller proportion within the 55 + age group, who are also under-represented within ‘worried sceptics’ (E), and ‘disengaged cynics’ (D) (see Table 9). There is a noticeable rise in the level of ‘worried sceptics’ (E) within the 25–34 and 35–44 age groups, and the largest proportions of ‘disengaged cynics’ (D) are within the 18–24 and 25–34 age groups. The 55 + age group is most represented amongst ‘wholehearted’ (A), ‘discerning proponents’ (B), and ‘on the fence’ (C). Markedly few who are < 44 years fell into ‘wholehearted’ (A). Chi-square cross-tabulation test showed that the association between age and segment membership was statistically significant (χ2(20) = 164.29, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The regression model accounted for a large proportion of variance in intentions indicating support for hypothesis 1. The HBM primary tier of influences suggests a considered risk evaluative decision-making approach of weighing pros and cons (barriers, cues, efficacy, and severity).

The addition to the model of TPB variables incorporates a broader set of values beyond the cost–benefit analysis; how it might feel to accept a vaccine, what respected others (SN), and media (SocN) would advise one to do and expected ability to accept a vaccine.

Lastly, the addition of the third set of factors into the model identified anticipated regret, if not accepting the vaccine when it should have been taken, as being the strongest driving force, providing partial support for the TPB [21] and HBM [14] theoretical frameworks, and the role of regret [44] in decision making.

Internal ability emerged as a weak, but statistically significant, negative influence, whereby those who believed that vaccine acceptance was up to them were slightly less likely to plan on accepting the vaccine. This aligns somewhat with the individualist social trends described by Giddens [20] and applied to vaccine hesitance by Hobson-West [19]. Neither populism nor political trust was registered as significant contributors to vaccine intentions amongst the total sample.

In relation to hypothesis 2, identification of distinct communities or ideological subsets, six distinct subsets were identified through sample clustering derived from different patterns of agreement with TPB, HBM, and other value-related constructs. ‘wholehearted’ (A) and ‘discerning proponents’ (B) registered above average, more proactive, and vaccine intentions, while ‘on the fence’ (C), ‘disengaged cynics’ (D), ‘worried sceptics’ (E), and ‘emphatic rejectors’ (F), indicated somewhat more hesitant vaccine intentions.

Wholehearted and discerning proponent segments expressed largely similar positive vaccine attitudes. More specifically, the wholehearted cohort, the largest cluster representing 1 in 4 amongst the sample, registered above-average endorsement for internal ability (vaccine acceptance is up to me), suggesting the ‘wholehearted’ label for the segment. The higher rating of social media as an influence on vaccine decisions further distinguishes this segment from the discerning proponents.

More research is required to understand the rationales behind ratings; however, due to their reduced reliance on social media segment B has been tentatively titled ‘discerning proponents’.

The third segment, segment C, represents just over a sixth of the sample, and this group did not deviate from the mean for a significant swathe of measures suggesting a less involved attitude to the debate, thus the suggested name ‘on the fence’.

Consistent with Kennedy’s 2015 finding [2] that populist attitudes are correlated positively with vaccine hesitancy, ‘emphatic rejectors’ expressed above-average agreement with all three populist statements while the ‘worried sceptics’ sub-group expressed above-average agreement with populist measures ‘anti-elitism and ‘antagonism towards elite’.

However, the correlation did not run as strongly in the other direction in that those in favour of vaccination did not tend to reject populist statements as strongly. On the other side of the vaccines fence, the pro-vaccine ‘wholehearted’ subgroup under-indexed on ‘anti-elitism’, and ‘discerning proponents’ under-indexed for ‘will of the people’ sentiment. Neither ‘on the fence’ or ‘disengaged cynics’ registered significant deviation from the mean for populist statements. The fact that ‘disengaged cynics’, with their low levels of trust suggested by the cluster name, did not differ from the average on any of the three populism measures, further suggests that populist political themes are by no means dominant across the Irish vaccine discourse.

‘Worried sceptics’ were given that label due to their high perceived risk, and engagement with normative influences, coupled with average levels of trust. Dissimilar to the other vaccine-negative segments, ‘worried sceptics’ registered high perceived severity for COVID-19 and did not register below-average perceptions of their susceptibility to the condition. This group expressed higher than average subjective norms and social norms at play, suggesting that they are exposed to endorsement of vaccination within their social network. Only the ‘worried sceptics’ and the ‘wholehearted’ clusters described themselves as paying above-average levels of attention to advise on social media, suggesting that vaccine recruitment of ‘worried sceptics’ may be usefully targeted through this channel.

The findings in this study suggest merit in focusing especially on ‘worried sceptics’ for any pro-vaccine interventions as they are the most worried and most social media engaged vaccine-hesitant group, as found in Faase and Newby 2020 research [16]; this group acknowledges COVID-19 risks and show a level of vaccine consideration, suggesting potential for increased positive correlation with health-protective behavioural intentions.

In terms of pro-vaccine interventions, Kozyreva et al. [30] describe three possible strands of intervention to address online misinformation; techno-cognition refers to technical interventions to the design architecture e.g. filtering out misinformation while nudges [49] also effect change to the choice environment to prompt desired actions and, finally, boosts are aimed directly at the individual, requiring active engagement in interventions that develop online cognitive competencies. Kozyreva et al. [30] also identify the need to counteract social calibration issues where small and spatially disparate groups [20] form large communities online, creating an illusion of consensus.

‘Emphatic rejectors’, the smallest cluster at 1 in 20 amongst the sample, registered the lowest vaccine intentions by a considerable margin. They display distinctively individualistic attitudes incorporating also high internal ability levels, which are not replicated amongst the other hesitant cohorts. This group expressed below-average likelihood to rely on every source of information listed.

Future research might examine whether vaccine-hesitant segments may share some kinship with those identified in the 2015 segmentation study by Ramanadhan et al. [17] in that a specific cohort who are heavily influenced by social media has been identified. That research found 2 small anti-vaccine segments along with 1 very large hostile cohort which might bear some kinship with the smallest Irish segment, ‘emphatic rejectors’.

Both the ‘wholehearted’ and ‘emphatic rejector’ clusters (who registered the highest, and the lowest, vaccine intentions respectively) expressed significantly elevated agreement with the internal ability statement. This boomerang effect [50] suggests the ‘up to me’ wording is received as positively influencing vaccine intentions by some but construed as a negative influence by others. This could be explained as psychological reactance [50] whereby vaccination represents a threat to freedom for some, resulting in negative cognitions accompanied by an affective anger response [35, 50]. This relationship between anger and threats to freedom is suggestive of the model presented by Turner [35] and Jang et al. [36] and as such warrants further study [50].

Vaccine hesitancy (segments C, D, E, and F) occurred significantly more frequently within the 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 age groups, consistent with Karlsson et al. [51]. In contrast to Galasso et al. (2020) findings [48], but consistent with the mixed-gender outcomes highlighted by Bish and Michie [15], no significant differences between females and males were found in relation to segment membership. This suggests, irrespective of gender, the need to focus on the younger age groups when devising pro-vaccine interventions.

Conclusions

The current research explored factors driving vaccine decision-making amongst a robust and broadly representative sample of Irish adults. Findings suggest that vaccine decisions are multi-faceted with both rational (cognitive) and emotive (affective) considerations at play. Segmentation identified 6 differentiated segments whose overall intentions to accept a vaccine ranged from highly favourable to highly unfavourable. The segment responses spread out largely along a spectrum of pro-vaccine to anti-vaccine, attitudes. However, differing decision-making emphases and differing levels of engagement with the topic could be seen, with weaker levels of engagement not necessarily aligning with an intention score closer to the mean. Noteworthy differences outside the pro/anti dichotomy emerged for norms (particularly around media), the self-efficacy measure, perceptions of COVID-19 severity, and susceptibility to COVID-19. Political themes were also found to feature but not dominate the debate: four segments, ‘emphatic rejectors’, ‘worried sceptics’, ‘discerning proponents’, and ‘wholehearted’, registered significantly higher or lower responses to populist measures while the lower involvements ‘on the fence’ and ‘disengaged cynic’ clusters were not differentiated in this regard. Presence or lack of political trust did not necessarily align with populist attitudes.

Recommendations

Influencers might usefully seek to address the algorithmic echo-chamber effect online by proactively engaging with diverse online communities. While the ‘right thing to do’ is clear when viewed through a lens of scientific expert advice, this is precisely the paradigm which populist movement rejects. To avoid further alienating already-marginalised cohorts, generic facts-based online messaging (while useful and important) should be supplemented with messages addressing more emotive concerns through prototypical language. Segmentations, such as the outputs from this study, afford a framework for developing and evaluating more refined, targeted, policies and interventions.

Weaknesses

The short-form survey would have benefited from a more extensive development and the inclusion of a preliminary qualitative stage to assist in question development. A quantitative survey pilot stage would have identified the poor link between the TPB ability and cues statements, allowing a refined set of questions to feed these dimensions into the K-means analysis.

Several potentially helpful measures were omitted from the study. A noteworthy omission from severity and susceptibility measures was whether respondents or their family members have pre-existing health conditions. Along the same lines, more concrete behaviour measures should build on the generic past health behaviour wordings used here to probe, for example, frequency of consulting HCP and acceptance of vaccines for other conditions for self or children. Given the relevance of age to COVID-19 susceptibility, respondent age-breaks might have been better broken out to distinguish the 65 + or 70 + cohort. Lastly, a set of political efficacy questions provided alongside the political trust and populism measures were omitted from the final survey. While the research was predicated on an assumption of online activity, the survey did not ask for details of online and social media activity.

Future directions

Future discriminant analysis would enable concepts to be tested alongside a shortened questionnaire assigning respondents’ segment membership. This would allow for replication of the segments, so that future research might investigate the base variables and widen the lens significantly beyond the current variable set.

Segment-specific engagement with diverse communities online and with specific conspiracy narratives warrants closer attention.

Further research should tease out the meaning of the dichotomous internal ability scores, to understand whether the phrase evokes the same meaning across segments and its relevance to psychological reactance [54] and/or ancillary concepts.

This research findings presented here omitted an open-ended qualitative survey section. A thematic analysis of the verbatim comments across segment groups may shed light on themes that emerged as significant in this analysis. The qualitative question on feelings evoked might be considered in the context of the efficacy/anger segmentation model presented by Turner [35], and Jang et al. [36].

Future research might also usefully include the political efficacy measure which was featured alongside political trust and populism in the source paper [39] but was omitted from this research. In addition, further research within segments C, D, E, and F might usefully explore the segment-specific reactions to a range of messaging and policy initiatives, with the aim to identify those initiatives with the most potential to encourage intentional shift, and ultimately vaccine acceptance, across attitudinal cohorts.

Availability of data and material

Full data set and analyses are available for review.

Code availability

SPSS and Sphinx IQ.

References

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020) COVID-19 VACCINES: SAFETY SURVEILLANCE MANUAL. Retrieved September 29, 2021 from. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/covid-19-vaccines-safety-surveillance-manual/covid19vaccines_manual_communication.pdf?sfvrsn=7a418c0d_1&Status=Master

Kennedy J (2019) Populist politics and vaccine hesitancy in Western Europe: an analysis of national-level data. Eur J Public Health 29(3):512–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz004

Union E (2018) STATE OF VACCINE CONFIDENCE IN THE EU 2018. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Wakefield A (1998) Autism, inflammatory bowel disease, and MMR vaccine. Lancet (London) 351(9112):1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79083-8

Toure A, Saadatian-Elahi M, Floret D et al (2014) Knowledge and risk perception of measles and factors associated with vaccination decisions in subjects consulting university affiliated public hospitals in Lyon, France, after measles infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother 10(6):1755–1761. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.28486

Parmet W (2010) Pandemic vaccines — the legal landscape. N Engl J Med 362(21):1949–1952. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1000938

Traynor V (2020) Settlement for teenager over swine flu vaccine. (RTE News) Retrieved March 1, 2021 from. https://www.rte.ie/news/courts/2020/1104/1175953-vaccine-case/#:~:text=High%20Court%20settlement%20for%20teenager%20over%20swine%20flu%20vaccine&text=The%20High%20Court%20has%20approved,flu%20vaccine%20ten%20years%20ago

Daly M, Robinson E (2021) Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the U.S.: Representative longitudinal evidence from April to October 2020. Am J Prev Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.008

Maynooth University (2020) COVID-19 Mental Health Survey by Maynooth University and Trinity College finds high rates of anxiety. Maynooth University. https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/news-events/covid-19-mental-health-survey-maynooth-university-and-trinity-college-finds-high-rates-anxiety. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Ipsos MRBI (2020) COVID-19 vaccine research. Ipsos MRBI. https://www.ipsos.com/en-ie/covid-19-vaccine-research. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Ad World (2020) RTÉ reveals state of the nation in new B&A research. Behaviour & Attitudes. https://www.adworld.ie/2020/10/02/rte-reveals-state-of-the-nation-in-new-ba-research/. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Ipsos MRBI (2020) Just-over-half-people-would-get-covid-19-vaccine-says-ipsos-mrbi-survey-ipha. Ipsos MRBI. https://www.ipsos.com/en-ie/just-over-half-people-would-get-covid-19-vaccine-says-ipsos-mrbi-survey-ipha. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Ipsos MRBI (2020) Ipsos MRBI/IPHA COVID vaccine tracker - January 2021. Ipsos MRBI. https://www.ipsos.com/en-ie/ipsos-mrbiipha-covid-vaccine-tracker-january-2021. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Rosenstock M (1966) Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 44:94–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/3348967

Bish A, Michie S (2010) Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: a review. Br J Health Psychol 15(4):797–824. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710x485826

Faasse K, Newby J (2020) Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004

Ramanadhan S, Galarce E, Xuan Z et al (2015) Addressing the vaccine hesitancy continuum: an audience segmentation analysis of American adults who did not receive the 2009 H1N1 vaccine. Vaccines 3(3):556–578. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines3030556

Gardner D (2009) Risk. Virgin Books, London

Hobson-West P (2003) Understanding vaccination resistance: moving beyond risk. Health Risk Soc 5(3):273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570310001606978

Giddens A (2012) The consequences of modernity. Polity, Cambridge

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

Ajzen I (2016) Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. Retrieved March 1, 2021 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235913732_Constructing_a_Theory_of_Planned_Behavior_Questionnaire. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235913732_Constructing_a_Theory_of_Planned_Behavior_Questionnaire. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 40(4):471–499

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

Agarwal V (2014) A/H1N1 vaccine intentions in college students: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Am Coll Health 6(62):416–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.917650

Priest Catalano H, Richards K, Hyatt Hawkins K (2017) Theory of planned behavior-based correlates of HPV vaccination intentions and series completion among University Students in the Southeastern United States. Health Educ 49(2):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2016.1269771

Gagnon M, Godin G (2000) Young Adults and HIV Vaccine: Determinants of the Intention of Getting Immunized. Can J Public Health 91(6):432–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03404823

Hamilton K, van Dongen A, Hagger M (2020) An extended theory of planned behavior for parent-for-child health behaviors: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 39(10):863–878

Johnson N, Velásquez N, Restrepo N et al (2020) The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature 582(7811):230–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1

Kozyreva A, Lewandowsky S, Ralph H (2020) Citizens Versus the Internet: Confronting Digital Challenges With Cognitive Tools. APS 21(3):103–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620946707

McRee A, Reiter P, Brewer N (2012) Parents’ internet use for information about HPV vaccine. Vaccine 30(25):3757–3762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.113

Jolley D, Douglas K (2017) Prevention is better than cure: addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. J Appl Soc Psychol 47(8):459–469

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020) COVID-19 VACCINES: SAFETY SURVEILLANCE MANUAL [Online]. Available. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/covid-19-vaccines-safety-surveillance-manual/covid19vaccines_manual_communication.pdf?sfvrsn=7a418c0d_1&Status=Master. Accessed 29 Sept 2021

Clatworthy J, Buick D, Hankins M et al (2005) The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: A review. Br J Health Psychol 10:329–358. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705x25697

Turner MM (2007) Using emotion in risk communication: the anger activism model. Public Relat Rev 33(2):114–119

Jang Y, Turner MM, Heo JR, Barry R (2021) A new approach to audience segmentation for vaccination messaging: applying the anger activism model. J Soc Mark Ahead of print

Recio-Román A, Recio-Menéndez M, Román-González MV (2021) Global vaccine hesitancy segmentation: a cross-European approach. Vaccines 9(6):617

Mudde C (2004) The populist zeitgeist. Gov Oppos 39(4):541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Geurkink B, Zaslove A, Sluiter R et al (2019) Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: old wine in new bottles? Political Stud 68(1):247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719842768

MacArthur K (2017) Beyond health beliefs: the role of trust in the HPV vaccine decision-making process among American college students. Health Sociol Rev 26(3):321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2017.1381035

Wong M, Wong E, Huang J et al (2021) Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 39(7):1148–1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083

Christy S, Winger J, Raffanello E et al (2016) The role of anticipated regret and health beliefs in HPV vaccination intentions among young adults. J Behav Med 39(3):429–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9716-z

Abraham C, Sheeran P (2003) Acting on intentions: the role of anticipated regret. Br J Soc Psychol 42:495–511. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603322595248

Brewer N, DeFrank J, Gilkey M (2016) Anticipated regret and health behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol 35(11):1264–1275

Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML (2020) Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 38(42):6500–6507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32863069; PMCID: PMC7440153

Dror A, Eisenbach N, Taiber S et al (2020) Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol 35(8):775–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y

Esomar.org, ESOMAR Code of Conduct’, Esomar 2021 [Online] Available. https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P et al (2020) Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117(44):27285–27291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012520117

Thaler R, Sunstein C (2009) Nudge. Yale University Press

Brehm SS, Brehm JW (1981) Psychological reactance: a theory of freedom and control. Academic Press, San Diego

Karlsson L, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S et al (2021) Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Differ 172:110590

Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese N, Sabat I et al (2020) Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ 21(7):977–982

Quinn S, Kumar S, Freimuth V, Kidwell K, Musa D (2009) Public willingness to take a vaccine or drug under emergency use authorization during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Biosecur Bioterror 7(3):275–290

Chen N-TN (2015) Predicting vaccination intention and benefit and risk perceptions: the incorporation of affect, trust, and television influence in a dual-mode model. Risk Ana 35(7):1268–1280

Cacciatore MA, Nowak G, Evan NJ (2016) Exploring the impact of the US measles outbreak on parental awareness of and support for vaccination. Health Aff. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1093

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rountree, C. (Interactions Research)—study conceptualisation, methodology, analysis and investigation, writing—original draft, review and editing. Prentice, G. R. (Psychology Department, Dublin Business School)—methodology, analysis and investigation, writing—original draft, review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Panel provider checked for compliance with the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR). Interactions checked for compliance with AIMRO codes of conduct.

Consent to participate

It is included within the panel’s terms and conditions.

Consent for publication

It is included within the panel’s terms and conditions.

Conflict of interest

Claire Rountree is employed by Interactions Ltd. Access to survey sample and survey design/hosting software was provided free of charge by Interactions Ltd.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Questionnaire

Appendix. Questionnaire

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rountree, C., Prentice, G. Segmentation of intentions towards COVID-19 vaccine acceptance through political and health behaviour explanatory models. Ir J Med Sci 191, 2369–2383 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02852-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02852-4