Abstract

Background

The mitigation measures implemented in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an overall abrupt decline in hospitalizations. Endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis are acute conditions that can lead to substantial morbidity and mortality when treatment is delayed. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitalizations for those conditions has not been fully explored.

Objective

To compare national trends of endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis hospitalizations in the US before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The ICD-10-CM codes from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data were used to identify hospitalizations for endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis occurring from 2018 through 2020 among individuals 18 years of age or older. Using an interrupted time series analysis design, we compared the number of hospitalizations for those conditions during the pandemic period (March 2020 to December 2020) to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic (January 2018 to February 2020). All reported numbers are weighted and represent national estimates.

Results

Among 76,762,573 all-cause hospitalizations occurring nationally from January 2018 to February 2020, 193,930 were for endocarditis, 21,685 for myocarditis, and 49,650 for pericarditis. During the pandemic period (March 2020 to December 2020), of the total 26,422,315 hospitalizations, 72,030 were for endocarditis, 13,480 for myocarditis, and 17,110 for pericarditis. Hospital length of stay significantly increased for all three conditions during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period: 13.4 versus 12.8 days for endocarditis (p ≤ 0.01), 8.7 days versus 6 days for myocarditis (p ≤ 0.01), and 6.7 versus 6.1 days for pericarditis (p ≤ 0.01). In-hospital mortality during the pandemic period for endocarditis was 11.1% versus 9.1% pre-pandemic (p ≤ 0.01), 16.8% versus 3.9% pre-pandemic (p ≤ 0.01) for myocarditis, and 4% versus 2.8% pre-pandemic for pericarditis (p ≤ 0.01). Interrupted time series analysis showed an immediate decrease in monthly admissions for endocarditis and pericarditis soon after the states’ COVID-19 shutdowns. However, myocarditis hospitalizations almost doubled from 880 in February 2020 to 1605 and 1740 in March and April 2020, respectively.

Conclusions

We observed an immediate increase in monthly hospitalizations for myocarditis and an immediate decrease in hospitalizations for endocarditis and pericarditis following the national COVID-19 lockdown compared to the pre-pandemic period. Length of stay and in-hospital mortality significantly increased during the pandemic period for all three health conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The first confirmed Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) case in the United States (US) was announced in January 2020. In March 2020, following the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organization, the United States started to implement shutdowns and stay-at-home orders [1]. Mitigation measures implemented to slow the spread of the novel virus included cancellations of non-urgent elective procedures and in-person visits, with a shift to telemedicine to accommodate the rapid surge in critically ill patients [2]. This resulted in a decline in hospital admissions from late March to late May of 2020 for common cardiovascular diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [3, 4], heart failure [5, 6], and stroke [7]. However, it remains uncertain whether less common cardiovascular diseases were similarly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Infectious and inflammatory conditions of the heart- namely infective endocarditis (IE), myocarditis, and pericarditis are relatively uncommon in the general population, with an annual incidence of 3–10 cases per 100,000 for IE [7, 8], 10 to 22 cases per 100,000 for myocarditis [9], and 27.7 cases per 100,000 population for pericarditis [10]. Despite their rarity, these conditions can lead to significant complications, including valve impairment in endocarditis [11], cardiomyopathy and heart failure in myocarditis [12], and multiple recurrences that lead to fibrosis in pericarditis [13].

Endocarditis hospitalizations have increased in the last decade primarily due to the opioid epidemic [14]. Extant research suggests that opioid use has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly due to social and economic stress [15, 16], posing the question of the effect of the pandemic on the rate of IE hospitalizations. In addition, the prevalence of comorbidities is high in persons with substance use disorder, putting them at a high risk of contracting the COVID-19 infection [17]. Emerging evidence also suggests an association between COVID-19 infection and population incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis [18].

Changes in hospitalizations and outcomes of common cardiovascular diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic are well studied; however, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions for endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis has been studied primarily in Europe [19, 20], it has not been addressed in the US. Given the unique characteristics of the US population—including the high prevalence of substance use disorder, the disproportionate impact of the opioid epidemic, and differences in healthcare accessibility—it is crucial to examine these conditions in the US context. This study compared national trends in endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis hospitalizations in the US before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to fill this gap in the literature.

2 Methods

2.1 Data source

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data for the years 2018 through 2020 were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), a family of healthcare databases and tools developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to enable research on hospital care and utilization in the United States. The NIS, one of the most extensive all-payer inpatient healthcare datasets in the country, covers 97% of hospitalizations from 46 states and the District of Columbia [21]. The data provide a stratified sample of 20% of hospital discharges from U.S. community hospitals, representing up to 7 million unweighted discharges yearly. The dataset includes a comprehensive range of de-identified clinical and nonclinical data elements, such as primary and secondary diagnoses, procedures performed during hospitalization, and patient demographics—including age, gender, race, and other factors. Additionally, it contains information on the primary payer for the hospitalization (e.g., private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or self-pay) and the length of the hospital stay.

2.2 Study population

The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes were used to identify hospitalizations with primary or secondary diagnoses for endocarditis (I330, I339, I39, I38, A3282, B376), myocarditis (B3322, I41, I400, I401, I408, I409, I514) and pericarditis (B3323, I300, I301, I308, I309, I32) among patients 18 years of age or older. A coexisting diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was identified based on ICD-10-CM codes (U071, U00, U49, U50, U85, J1282) (Supplemental, Table S1). We defined the time from January 2018 to February 2020 as the pre-pandemic period and from March 2020 to December 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic period.

2.3 Study variables and outcomes

Baseline characteristics included patients’ demographics (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), insurance status (Medicare/Medicaid/Private/Others), and hospital location (Northeast/Midwest/ South/West).

The primary outcome of interest was the monthly number of hospitalizations for each of the three heart conditions. The secondary outcomes were length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality.

2.4 Statistical analysis

In accordance with HCUP guidelines, the statistical analysis incorporated key variables to account for the complex multistage sampling design of the NIS dataset. Specifically, the DISCWT variable was used for weighting to generate nationally representative estimates, the NIS_STRATUM variable accounted for stratification by hospital characteristics, and the HOSP_NIS variable adjusted for clustering at the hospital level. These variables were applied within the SAS Proc Survey procedure, ensuring accurate variance estimation and reliable standard errors for national hospitalization estimates [22]. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables. The Chi-square test was used to compare percentages prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The mean and standard error are reported for continuous variables with a t-test for the comparison of means.

In an interrupted time series analysis design, the COVID-19 national emergency declaration, which was declared on March 11, 2020 and ended on May 11, 2023, was considered as a possible interruption (intervention) [23] to the monthly trends of endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis hospitalizations. Segmented regression analysis was performed using the Proc Autoreg procedure described by Slavova et al. [24, 25] to assess changes in hospitalization trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, modeling the number of monthly hospital admissions trends for each disease. The results had two segments, each with a regression line defined by an intercept and a slope parameter—the intercept represents the level of hospital admissions at the start of the segment, and the slope represents the average change (trend) in the monthly hospital admissions during the time segment. We used the following model:

where \({Y}_{t}\) represents the number of hospitalizations in the month t for each of the diseases, and \({month}_{t}\) represents the time variable, which starts at 0 (January 2018) and ends at 35 (December 2020). The national emergency variable is coded as 0 for admissions before March 2020 and 1 otherwise. The m \(onth\_after\_national\_emergency\) variable is given a value of 0 for the pre-pandemic period and a value between 1 and 10 for the pandemic period. An example of the data preparation for segmented regression analysis is provided in Supplemental Table S2. The \({\beta }_{^\circ }\) coefficient represents the intercept at baseline,\({\beta }_{1}\) estimates the change in the monthly hospitalizations pre-pandemic, \({\beta }_{2}\) estimates the immediate change in the intercept after the national emergency declaration and \({\beta }_{3}\) represents the change in the monthly hospitalization rate (slope) during the pandemic period.

A sensitivity analysis was performed using the monthly hospitalization rates, calculated by dividing the number of monthly admissions of the disease of interest by the total number of hospital admissions for all causes in that month, multiplied by 100,000.

Data analyses were performed using SAS software 9.4, Copyright © 2002–2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. The statistical significance threshold was set to ≤ 0.05.

3 Results

A total of 35,527,490 and 35,419,025 hospitalizations occurred in 2018 and 2019, respectively. In 2020, the total hospitalizations were modestly lower at 32,355,825 (Supplemental, Figure S1).

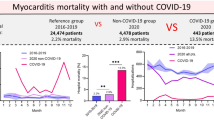

Monthly hospitalizations for endocarditis decreased from 7655 hospital admissions in January 2020 to 6245 hospital admissions in April 2020 (Fig. 1). Similarly, monthly hospital admissions for pericarditis decreased from 1860 in February 2020 to 1285 in April 2020 but rebounded to pre-pandemic numbers in July 2020. In contrast, the number of hospitalizations for myocarditis increased from 880 hospital admissions in February 2020 to 1740 in April 2020.

3.1 Endocarditis

Of the 265,960 endocarditis admissions identified from 2018 to 2020, 193,930 (72.9%) occurred in the pre-pandemic period and 72,030 (27.1%) during the pandemic (Table 1). All-cause-in-hospital mortality for IE hospitalizations was 11% during the pandemic compared to 9% pre-pandemic (p < 0.01). The average length of hospital stay was significantly higher during the pandemic period (13.4 days, SE = 0.2) compared to the pre-pandemic period (12.8 days, SE = 0.1, p < 0.01). The proportion of endocarditis admissions associated with injection drug use did not differ between the two study periods (26.6% versus 26.8%, p < 0.8). There was no difference in the proportion of patients with endocarditis who underwent valve surgery before or during the pandemic period. We observed a slight decrease in the proportion of patients who had a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) during the pandemic period (22.7%) as compared to before the pandemic (24.3%; p < 0.03). We observed an immediate decrease in the monthly admissions for endocarditis by − 885.7 (95% CI − 1513.5, − 257.8) following the states’ shutdown in March 2020 (Fig. 2A).

3.2 Myocarditis

From 2018 to 2020, there were 35,165 hospitalizations for myocarditis, 13,480 (38.3%) of which occurred between March 2020 and December 2020 (Table 1). The mean age of patients admitted for myocarditis during the pandemic period was 54.7 (SE = ± 0.4) years, in comparison to 46.7 (SE = ± 0.3) years during the pre-pandemic period (p < 0.01). Hispanic patients represented 17.6% of the hospitalizations during the pandemic, whereas they accounted for only 2.7% of the admissions in the pre-pandemic period (p < 0.01). Moreover, the average length of hospital stay for myocarditis increased from 6 (SE = 0.2) days before the pandemic to 9 (SE = 0.3) days during the COVID-19 pandemic (p < 0.01). During the pre-pandemic period, the in-hospital mortality among patients hospitalized with myocarditis was 3.9%, while during the pandemic period, it rose to 16.8% (p < 0.01). Notably, during the pandemic, 40% of myocarditis admissions were associated with a coexisting COVID-19 infection.

The segmented regression analysis showed an abrupt increase in the monthly number of myocarditis hospitalizations by 613.5 (95%CI 347.3, 879.7), occurring shortly after March 2020 (Fig. 2B, Table 2).

3.3 Pericarditis

Of the 66,760 admissions for pericarditis identified throughout the study period, 17,110 (25.63%) occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). There were no detectable differences in the average age or sex distribution of patients admitted before or during the pandemic. However, it is noteworthy that the in-hospital mortality among patients admitted with pericarditis was 4% during the pandemic, whereas it was 2.8% before the pandemic (p < 0.002). Additionally, a coexisting diagnosis of COVID-19 was present in 5% of the admissions.

Furthermore, the segmented regression demonstrated a significant decline in the monthly pericarditis admissions following March 2020 (− 459.1, 95%CI − 620.5, − 297.8), (Fig. 2C, Table 2). However, pericarditis admissions continued to increase gradually and exceeded the pre-pandemic number of hospitalizations by July 2020, with a slope (trend) of 43.4 (95%CI 20.1, 66.8).

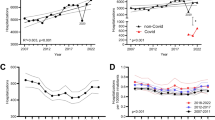

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

Unlike the primary analysis, the sensitivity analysis showed an immediate increase in the number of endocarditis monthly hospitalization rates during the pandemic period (Supplemental, Figure S3, A). The pre-pandemic monthly hospitalization rate for IE was 245.5/100,000 all-cause hospital admissions (95%CI 242.6, 248.8). The immediate intercept change (level change) for IE after March 2020 was 25.4 IE hospitalizations per 100,000 all-cause hospital admissions (95%CI 6.8, 43.9) (Supplemental, Table S3).

For pericarditis and myocarditis, the sensitivity analysis showed similar results to our primary analysis (Supplemental, Figure S3, B &C).

4 Discussion

We observed a significant decrease in hospitalizations for endocarditis as well as pericarditis in association with the onset of the pandemic. This initial reduction was followed by a steady increase to the pre-pandemic levels by the end of December 2020. In contrast, the number of myocarditis admissions increased immediately following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US and continued to increase through December 2020. This observation aligns with the CDC morbidity and mortality weekly report that showed a rise in myocarditis hospitalizations between April and May 2020 [18]. Our results also match trends in France reported by Pommier et al. [26].

While this observational study cannot support a causal relationship between the COVID-19 viral infection and diseases of the myocardium, 40.9% of patients admitted for myocarditis during the pandemic period had a coexisting COVID-19 infection. From a pathophysiology perspective, the COVID-19 virus can affect the myocardium by direct cell invasion via ACE2 receptors [27]. COVID-19 virus can also cause collateral damage to the myocardium by activating an immune response or lead to widespread inflammation in the heart due to a cytokine storm [28, 29].

We also observed higher mortality among patients admitted with myocarditis during the pandemic period as compared to the pre-pandemic period (3.9% pre-pandemic versus 16.8% during the pandemic, (p < 0.01). Possible explanations include older age of patients admitted during the pandemic, greater multimorbidity, and a COVID-19 coexisting diagnosis [30]. Additionally, managing chronic and acute diseases during the pandemic was suboptimal for many patients within the overwhelmed healthcare system. The observed significant increase in the length of stay at the hospital may be attributed to patients delaying seeking timely medical care for fear of contracting the virus, which could have led to more severe disease at presentation [31]. Additionally, medical staff burnout and shortages, which strained healthcare delivery systems, may have also contributed to prolonged hospital stays [32]. Furthermore, the significant increase in the proportion of Hispanic patients hospitalized with myocarditis during the pandemic period (17.6% versus 2.7% pre-pandemic) raises important questions about potential disparities in healthcare access, exposure risk, or disease severity among racial minorities [33], however, those potential explanations can’t be confirmed in this study and further investigation is required.

We also observed a decline in monthly endocarditis hospitalizations during the pandemic, which matches reports conducted in France and Belgium [19], Spain [20], and China [34]. The decline in endocarditis admissions can be explained by the overall decline in healthcare utilization during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic [35] or the reduction in using diagnostic procedures [36]. Performing transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is considered a class I indication for suspected endocarditis cases and the gold standard diagnostic test. However, due to TEE being “an aerosol-generating procedure” with the easy transmission of COVID-19 to healthcare workers, the use of TEE for IE diagnosis was limited, especially early on during the Pandemic (March and April 2020) [37, 38]. Nevertheless, our study observed an increase in endocarditis admissions from May 2020 to September 2020, which can be explained by a change in patients’ behavior in seeking medical help or a change in healthcare providers’ behavior in ordering more diagnostic procedures after the national lockdown. There is currently no strong evidence to support a direct causative association between COVID-19 infection and endocarditis. While a few case reports have described concomitant occurrences of COVID-19 and infective endocarditis, these cases primarily reflect co-infections rather than a direct causative relationship [39]. There has not been strong evidence in the literature that suggests a direct association between COVID-19 infection and endocarditis.

The sensitivity analysis for endocarditis using the rates of hospitalizations showed an immediate increase after March 2020. Rates are particularly valuable when examining time trends and assessing whether the observed changes over time are due to actual shifts or are merely artifacts of changes in population size or structure. The increase in the rates of hospitalizations of IE could reflect the overall decrease in healthcare utilization during the pandemic, as the data shows that the total number of all-cause hospitalizations in 2018 and 2019 (35,527,490 and 35,419,025) is higher than the hospitalizations in 2020 (32,355,825).

We also report an immediate and slight decrease in pericarditis hospitalizations after March 2020, rebounding to a higher number of monthly admissions throughout the study period. Reports on trends in pericarditis admissions before and during the pandemic are limited. Similar to myocarditis, several studies suggested an association between COVID-19 infection and pericarditis [40, 41] and between COVID-19 vaccination and pericarditis [42]. The observed decline in pericarditis admissions during the first few months of the lockdown could be explained by the overall reduction in healthcare utilization. The observed significant rebound might reflect an association between the COVID-19 infection and the risk of developing pericarditis as a complication.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that the use of NIS from 2018 to 2020 allowed for the examination of trends in hospitalizations for an extended period before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and comparison of those with hospitalizations occurring during several months following the national lockdown and prior to the first vaccine roll-out.

Study limitations should be noted. Importantly, the use of administrative healthcare data and the ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for identifying diseases of interest introduces the possibility of disease misclassification. Further, the NIS data does not allow to follow individual patients over time, as the dataset is de-identified and treats each hospitalization as an independent event. Additionally, the interrupted time series analysis is commonly utilized to examine the impact of interventions or policy changes, where a specific implementation date can be identified. The application of this method to natural disasters, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, presents challenges in determining a precise start date. Lastly, as the data from the years 2021 and 2022 are unavailable, we could examine hospitalizations for only 10 months of the pandemic period.

5 Conclusion

Results of this study indicate a notable increase in the number of monthly hospitalizations for myocarditis and a reduction in the hospitalizations for endocarditis and pericarditis following the national COVID-19 lockdown compared to the pre-pandemic period. To comprehensively grasp the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these three conditions, further studies with an extended follow-up for the latter years post-pandemic are warranted. Additionally, there is a compelling need for more research exploring the relationship between COVID-19 infection and the heightened risk of developing myocarditis and pericarditis.

These findings have practical implications, as monitoring hospitalization trends for rare cardiac conditions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic can guide healthcare preparedness and resource allocation. Identifying factors behind these changes can help address healthcare disruptions, protect racial minorities, and improve readiness for future emergencies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed for the current study are not publicly available. However, the data are available for purchase through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and can be accessed via this link: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp.

References

CDC. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2023.

Pujolar G, Oliver-Anglès A, Vargas I, Vázquez M-L. Changes in access to health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031749.

Solomon MD, et al. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2015630.

Garcia S, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011.

Barghash MH, Pinney SP. Heart failure in the COVID-19 pandemic: where has all New York’s congestion gone? J Card Fail. 2020;26(6):477–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.04.016.

McIlvennan CK, Allen LA, Devore AD, Granger CB, Kaltenbach LA, Granger BB. Changes in care delivery for patients with heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a multicenter survey. J Card Fail. 2020;26(7):635–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.05.019.

Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;387(10021):882–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00067-7.

Rajani R, Klein JL. Infective endocarditis: a contemporary update. Clin Med. 2020;20(1):31–5. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.cme.20.1.1.

Olejniczak M, Schwartz M, Webber E, Shaffer A, Perry TE. Viral myocarditis-incidence, diagnosis and management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(6):1591–601. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2019.12.052.

Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1498–506. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12763.

Cuervo G, Escrihuela-Vidal F, Gudiol C, Carratalà J. Current challenges in the management of infective endocarditis. Front Med. 2021;8: 641243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.641243.

Tschöpe C, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(3):169–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-00435-x.

Adler Y, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318.

Cooper HLF, Brady JE, Ciccarone D, Tempalski B, Gostnell K, Friedman SR. Nationwide increase in the number of hospitalizations for illicit injection drug use-related infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2007;45(9):1200–3. https://doi.org/10.1086/522176.

Faust JS, et al. Mortality from drug overdoses, homicides, unintentional injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and suicides during the pandemic, March-August 2020. JAMA. 2021;326(1):84–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.8012.

Friedman J, Akre S. COVID-19 and the drug overdose crisis: uncovering the deadliest months in the United States, January-July 2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(7):1284–91. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306256.

Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):30–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00880-7.

Boehmer TK. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data—United States March 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5.

Cosyns B, Motoc A, Arregle F, Habib G. A plea not to forget infective endocarditis in COVID-19 era. Jacc Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(11):2470–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.07.027.

Escolà-Vergé L, Cuervo G, de Alarcón A, Sousa D, Barca LV, Fernández-Hidalgo N. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis, management and prognosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(4):660–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.022.

HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed 17 Jan 2023.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). HCUP-US NIS description of data elements. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098.

Slavova S, et al. Interrupted time series design to evaluate the effect of the ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM coding transition on injury hospitalization trends. Inj Epidemiol. 2018;5(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-018-0165-8.

Slavova S, Rock P, Bush HM, Quesinberry D, Walsh SL. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214: 108176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176.

Pommier T, et al. Trends of myocarditis and endocarditis cases before, during, and after the first complete COVID-19-related lockdown in 2020 in France. Biomedicines. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10061231.

Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.

Thakkar S, et al. A Systematic review of the cardiovascular manifestations and outcomes in the setting of coronavirus-19 disease. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2020;14:1179546820977196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179546820977196.

Fairweather D, Beetler DJ, Di Florio DN, Musigk N, Heidecker B, Cooper LT. COVID-19, myocarditis and pericarditis. Circ Res. 2023;132(10):1302–19. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.321878.

Buckley BJR, Harrison SL, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Underhill P, Lane DA, Lip GYH. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of myocarditis and pericarditis in 718,365 COVID-19 patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13679.

Fardman A, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the Covid-19 era: Incidence, clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes-a multicenter registry. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6): e0253524. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253524.

Chun SY, Kim HJ, Kim HB. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the length of stay and outcomes in the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2022;9(2):128–33. https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.21.058.

Leuchter RK, Villaflores CWA, Norris KC, Sorensen A, Vangala S, Sarkisian CA. Racial disparities in potentially avoidable hospitalizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(2):235–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.036.

Liu X, Miao Q, Liu X, Zhang C, Ma G, Liu J. Outcomes of surgical treatment for active infective endocarditis under COVID-19 pandemic. J Card Surg. 2022;37(5):1161–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocs.16280.

Moynihan R, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3): e045343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343.

Van Camp G, et al. Disturbing effect of lockdown for COVID-19 on the incidence of infective endocarditis: a word of caution. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01686-x.

Hartley A, et al. Restricted use of echocardiography in suspected endocarditis during COVID-19 lockdown: a multidisciplinary team approach. Cardiol Res Pract. 2021;2021:5565200. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5565200.

Bracco D. Safe(r) transesophageal echocardiography and COVID-19. Can J Anaesth. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01667-8.

George A, Alampoondi Venkataramanan SV, John KJ, Mishra AK. Infective endocarditis and COVID-19 coinfection: an updated review. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2022;93(1): e2022030. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v93i1.10982.

Theetha Kariyanna P, et al. A Systematic Review of COVID-19 and Pericarditis. Cureus. 2022;14(8): e27948. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27948.

Patone M, et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28(2):410–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01630-0.

Block JP, et al. Cardiac complications after SARS-CoV-2 infection and mRNA COVID-19 vaccination—PCORnet, United States, January 2021–January 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(14):517–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7114e1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. performed the data analysis, prepared figures and tables and wrote the initial manuscript draft. S.B. provided feedback and supervision and reviewed the manuscript. S.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. A. K.N. provided feedback and supervision and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marji, M., Browning, S., Leung, S.W. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitalizations for endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis using an interrupted time series analysis of the United States National Inpatient Sample 2018 to 2020. Discov Epidemics 2, 4 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44203-025-00008-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44203-025-00008-9