Abstract

The article raises the issue of the quality of life (QoL) of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, its relationships with coping and mediating role of the received social support (RSS). The nationwide survey was conducted from September 13, 2021 to October 1, 2021. The total of 4970 individuals aged 10–18 years old were researched in Poland. The KIDSCREEN-27, the Brief COPE by Charles S. Carver in the Polish adaptation and the Berlin Social-Support Scales were employed in the research. SPSS and PROCESS macro were used for descriptive, correlational, and mediation analyses. The results indicate the relationship between the perceived QoL (QoL) with active coping, seeking social support coping and helplessness coping. The essential mediating role of the RSS was confirmed for the relationship between coping with stress and QoL in the group of the individuals researched. The findings imply that both in daily and difficult situations, social systems of support should be activated to provide environment for optimal development of adolescents, diminish consequences of potential risk factors, and enhance the significance of protective factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the society worldwide. Some groups of people felt its effects more than others due to the experience of additional difficulties. Adolescents as a developmental group were found in particularly difficult circumstances. The effort associated with growth and development as well as the experience of developmental crisis of the adolescents fell on the period of pandemic; numerous restrictions, anxiety and sense of threat. Such hard time of transition from childhood to adulthood was overloaded with all additional impediments resulting from the pandemic.

The review of 16 quantitative studies conducted from 2019 to 2021 on 40,076 respondents worldwide provides evidence that adolescents of various origins experienced higher anxiety, depression and stress rates due to the pandemic. Moreover, they used alcohol and Indian hemp more frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic1. The research also shows resources conditioning their QoL and positive adaptation that constitute protective factors of health during the pandemic. The most common protective factors mentioned are as follows social support, positive competences of coping and good relationships with their parents, practice based on belief, positive mindset and establishing social support2.

Coping with stress is one of the crucial resources of strategic significance for adjustment and QoL of adolescents. Furthermore, it can take on functions of adaptative and developmental behaviours or risky behaviours associated with the development of maladjustment. The selection of coping strategy depends on the individuals’ entity capital, namely resources (knowledge, skills, personality traits, experience), judgement of a difficult situation and its significance for individuals and environmental conditions (especially the presence of support). Coping with stress expresses individuals’ ways of behaviour in response to psychological stress. Coping strategies can be divided into emotional coping (contact with emotions, expression of emotions, regulation of emotions), cognitive coping (focused on solution) and escaping coping (based on denial of obstacles, passivity or flight from harsh reality to substitute behaviours)6,7,8.

The theoretical background for the considerations undertaken in the article is Stevan Hobfoll’s Theory of Conservation of Resources (COR). According to the COR, a person’s functioning in a situation of stress (pandemic) depends on the resources they have and may be expressed by a sense of QoL. Stress occurs when resources are lost and/or seriously threatened. Individuals with large reserves of resources have a significant chance of surviving traumatic events in good mental condition, especially when the return to mental balance is supported by external support resources. Difficulties arise when the demand for resources increases in relation to their availability. In the absence of individual and community reserves, a spiral of further resource losses is created. Successive cycles of loss accelerate and individuals’ ability to rebuild dwindling resource reserves is limited by the overwhelming nature of short time and adverse circumstances3,4,5. In the study, the QoL perceived by the adolescents surveyed was defined as the dependent variable. Resources can be broadly divided into internal (subjective) and external (environmental). Adaptive strategies for coping with stress are subjective resources and they were assumed to be an independent variable in this study. In the model presented, external resources include available support, e.g. from family members, teachers, specialists, manifested as a sense of support. This variable acts as a mediator.

Relationship of coping with stress with QoL in adolescents

Studies indicate that active coping with stress and using social support favour higher level of QoL9,10. Proactive coping (active, focused on solution) favours the development of mental resilience and depends on entity resources individuals have and acquire as well as environmental resources (social support). Social support is of great importance for positive interpretation of a stressful situation and promotes positive coping strategies11.

The research carried out on 577 Polish students from 17 universities revealed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, most frequently used coping strategies were as follows: acceptance, planning and seeking emotional support12. Large-scale research performed in Austria on 1,495 respondents showed that coping strategies that correlated positively with mental health are positive reframing, acceptance and humour13. The Polish research on the youth with mild intellectual disability (n = 151) confirmed positive relationship of active prosocial coping and satisfaction with life14. Active coping was associated with development of both resilience and their own interests, which is referred to as engagement coping15,16. This coping correlates positively with a higher sense of QoL17. Spanish research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that engagement coping was positively correlated with positive adjustment while disengagement coping correlated with a higher level of behavioural and emotional difficulties18. Similar dependences were verified in the study of young adults in Poland. Active coping correlated positively with QoL during the pandemic in turn, helplessness coping showed negative relationships with QoL. Helplessness coping was also a significant mediator of the relationship between resources distribution and QoL, and decreased positive relationships between benefits of resources and QoL, and increased negative relationships between loss of resources and QoL19.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the level of QoL in the adolescents was dependent on such entity resources like resilience, coping with stress and spending free time. Positive moderate correlations were obtained between the general sense of QoL and active coping and seeking social support. Moreover, negative moderate correlation was found between the general QoL and helplessness coping. The QoL increased along with the more frequent use of active coping strategies and the rarer use of helplessness coping encompassing withdrawal, self-blaming and substance use19.

Support received as resource

The significance of social support is based on the fact that there is an exchange of resources between the individual supporting and the individual supported in the relationship. Depending on the type of the exchange of resources, the following types of support can be distinguished20,21:

-

Emotional – conveying calming emotions that increase self-esteem and reflect concern, care and the sense of belonging.

-

Informational – an exchange of messages necessary for better comprehension of the situation, circumstance or problem, as well as provision of feedback on effectiveness of coping activities taken by an individual being supported.

-

Instrumental – a kind of briefing based on informing about certain ways of coping in a specific situation that constitutes a form of modelling of undertaken coping.

-

Appraisal – the provision of help to solve moral dilemmas and conveying signals that make individuals feel worthy and accepted.

-

Tangible – the provision of material and financial help for individuals in need.

The research performed based on the COR Theory indicates that a higher level of RSS in the case of traumatic events, increases considerably resilience to traumatic stimuli22. However, a lower level of perceived aid constitutes one of the most important predictors of negative effects of stress, among other things, unrealistic perception of the world (as hostile, dangerous and threatening), depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)23,24,25,26,27,28.

The significance of RSS in functioning of adolescents confirm the research carried out in the COVID-19 pandemic. On the basis of the research parental supportive activities were found to lead to the trigger and/or enhancement of developmental and adoptive mechanisms under stress (traumatic or chronic). They included among other things:

-

Constructive fulfilment of psychological needs35;

-

An increase in positive emotions31;

-

Preference of a positive lifestyle such as spending free time together, taking up different activities, fulfilling duties, engagement in hobbies and creative activities, spending free time outdoors36,37,38,39;

-

A higher level of prosocial behaviours in comparison with the period prior to the pandemic40;

-

A higher level of social skills including cooperation and mutual problem solving41,42,43;

-

Achievement of positive outcomes in online learning, among other things due to parents’ IT skills and access to digital devices44;

-

A lower risk of stress-related disorders - particularly due to parental emotional support during the quarantine period46,47;

-

Buffering a risk of negative responses/mental disorders to experienced stress, among other things, depressive and anxiety disorders48,49.

The aim of the study was to examine the significance of different coping strategies for the QoL in the adolescents and the role of RSS for relationships between the preferred coping strategies and the QoL in the adolescents under stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. On the basis of the research results presented, the following hypotheses were formulated on dependences between the preferred coping with stress strategies and QoL in the adolescents:

H1: In the adolescents, positive relationships are found between the experienced QoL and coping with stress by using two coping strategies in stressful situations, namely active coping and seeking social support.

H2: There is a negative correlation between QoL in the adolescents and the preferred passive coping with stress.

The subsequent two hypotheses refer to mediating roles of received social support by the adolescents:

H3: RSS in the group of the adolescents constitutes a mediator for relationship between experienced QoL and coping with stress by using active coping strategies and seeking social support. The mediating roles of RSS depend on the fact that active coping and seeking social support are associated positively with received support from others that, in turn, translates into an increase in QoL.

H4 RSS is a mediator for relationships between QoL in the adolescents and passive coping with stress. The mediating role of RSS is based on the fact that received aid, on the one hand, suppresses the use of passive coping with stress and, on the other hand, it is positively associated with QoL.

Methods

The nationwide survey was conducted from September 13, 2021 to October 1, 2021. The sampling scheme included two stages. In the first stage, it was assumed to draw a minimum of 1,200 schools from all over Poland (16 regions). In this study, a stratified random sampling design was used to improve the sample’s representativeness. The selection of schools was carried out on the basis of publicly available data, collected in the Register of Schools and Educational Institutions (https://rspo.gov.pl/). The research sample included 1228 units, including 868 elementary schools and 333 post-primary schools. A random sampling was then carried out based on selecting the appropriate number of schools of a given type for each region of Poland using a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG). This procedure made it possible to identify specific units from which all students were able to take part in the survey (each person included in a given group had a non-zero probability of taking part in the survey). To ensure the representativeness of the results, the next sampling draw was conducted. The draw sampling included control of the following characteristics: province of residence, type of residence and gender of the respondents.

Participants were invited to complete a set of questionnaires and then return them personally to research assistants. No time limitations were imposed on the participants. The participants were fully briefed of the aim of the study, and their queries were clarified by the researchers. The study was anonymous. The supervisors of the study were the employees of the Institute of Psychology and the Institute of Sociological Sciences of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (the 2013 revision). To comply with the ethical standards, the research was conducted according to the standards of good research practice recommended by the American Psychological Association. The procedure was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Sociological Sciences at the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (protocol code: 19/DKE/NS/2020).

The investigators obtained permission from each school principal to recruit adolescents for the study. The participation in the study was preceded by obtaining informed consent from the legal guardian of each child. The legal guardians were informed about the study by teachers via the school diary.

The survey was set up so that the legal guardian of potential participants had to click on a button indicating that they had read the consent information and agreed to their child’s participation in the survey. Once the button was clicked, the potential participant was directed to the research survey questionnaire. The survey questions were not displayed to participants until the legal guardians had clicked on the response to indicate voluntary participation in the study. Data were stored in a secure, encrypted database available only to the research team. No personal data were collected. The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Measurements

The QoL was assessed by the KIDSCREEN-27 instrument that consists of 27 items encompassing 5 dimensions of the QoL and the result of generalized sense of satisfaction50. A respondent replies referring to the last week on the scale of frequency (never, almost never, sometimes, almost always, always) or intensity (not at all, slightly, moderately, very, extremely). Solely the first general question about health is replied differently, determining health as excellent, very good, good, fair and poor. In most items positive orientation was assumed – the higher the score, the higher the QoL. The questionnaire has good psychometric properties; Cronbach’s alpha for adolescents was 0.93.

Coping with stress was assessed by means of the Brief COPE by Charles S. Carver51 in the Polish adaptation by Z. Juczyński and N. Ogińska-Bulik. It comprises 28 items on a 4-point scale; from 0 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 3 (I’ve been doing this a lot). This scale measures frequency of using 14 coping strategies. The strategies are divided into 7 factors: active coping (active coping, planning, positive reframing), helplessness (substance use, behavioural disengagement, self-blame), seeking support (use of emotional support, use of instrumental support), avoiding (self-distraction, denial, venting), turning to religion, acceptance, humour52. Split-half reliability for respondents aged 10–15 years old (N = 672) measured by the Guttman coefficient was 0.81, in turn for a sample of older respondents aged 16–19 years old (N = 703) it was 0.77.

The RSS in the group of adolescents was assessed by means of the scale compiled by the authors. The notion of social support was taken from Schiltz and Schwarzer, the authors of the Berlin Social-Support Scales (BSSS)53. The factor analysis conducted on the results obtained in the appropriate study of the sample (N = 4828) of the individuals aged 10–19 years old enabled the provision of two dimensions of social support. The ultimate questionnaire included 17 items on perceived (PSS) and received support. The respondents took their stance on the 4-point scale: strongly disagree‚ somewhat disagree‚ somewhat agree and strongly agree. Coefficient of reliability Cronbach’s alpha for the scale of PSS was 0.91 and for RSS was 0.93.

Statistical analysis

A series of correlation analyses and mediation analyses were performed. First, zero-order correlations among the variables were analyzed. The mediation analysis was performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by Preacher and Hayes54, using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and PROCESS macro for SPSS. The significance of indirect effects was tested using the bootstrapping procedure. Unstandardized indirect effects were computed for each of the 5,000 bootstrapped samples; the 95% confidence interval was also computed. In accordance with the recommendations provided in the literature, mediation effects were considered significant when the values of the mean estimated indirect effect fell within the 95% confidence interval, with the result that this interval did not include zero. It is assumed that for a mediation effect to be detected there must be significant relationships between the independent variable and the mediator (path a), and between the mediator and the dependent variable (path b). In the first step, the aim was to determine the correlation between psychological capital and QoL (path c). In the second step, the aim was to examine the mediating role of hope of success (path a × b). Bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals were used. If zero is not included in the 95% CI, the mediating role (c’) is statistically significant.

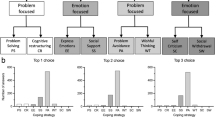

Figure 1 depicts a conceptual diagram of a simple mediation model. Coping with stress denotes the independent. RSS denotes the mediator or intermediary variable. QOL denotes the dependent or consequent variable. Path a represents the relationship between coping with stress and RSS. Path b represents the relationship between RSS and QOL when controlling for coping with stress. Path c represents the relationship between coping with stress and QOL (total effect). Path c’ represents the relationship between coping with stress and QOL when controlling for RSS (direct effect).The indirect effect is the product of a × b. The total effect is the sum of the direct and the indirect effect (c = c’ + a × b).

Results

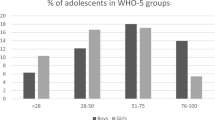

The mean age was 12.3 years (SD = 3.23). The characteristics of the participants are included in Table 1.

Correlations between the variables analysed

A moderate positive correlation was found between active coping and QoL (r = .41; p < .001). The seeking support was also positively correlated with QoL (r = .48, p < .001). Helplessness was negatively related to QoL (r = − .46, p < .001). The RSS was moderately and positively correlated with QoL (r = .51, p < .01). Thus, the hypothesis 1 and 2 were confirmed (Table 2).

Mediation analyses

Hypotheses 3–4 were tested in a series of mediation analyses whose aim was to establish if RSS was a mediator between coping with stress and QoL.

The analyses revealed significant direct relationships between active coping and RSS (β = 0.44, p < .001) and between active coping and QoL (β = 0.41, p < .001). The direct effect of the mediating variable (RSS) on QoL was also significant (β = 0.40, p < .001). The direct effect of active coping on QoL after adding RSS as a mediator decreased (β = 0.24, p < .001), indicating partial mediation. Significant direct relationships were found between seeking support and RSS (β = 0.55, < 0.001) and between seeking support and QoL (β = 0.48, p < .001). The direct effect of the mediating variable (support received) on QoL was also significant (β = 0.35, p < .001). The direct effect of seeking support on QoL after adding mediator decreased (β = 0.29, p < .001). Significant direct relationships were found between helplessness and RSS (β = − 0.23, < 0.001) and between helplessness and QoL (β = − 0.46, p < .001). The direct effect of the mediating variable (RSS) on QoL was also significant (β = 0.42, p < .001). The direct effect of helplessness on QoL after adding mediator decreased (β = − 0.36, p < .001). The results of the bootstrapping analysis confirmed the mediating role of RSS. Regression weights and coefficients of the indirect effects (paths a × b) are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The discussion of the authors’ own research results is presented based on the COR Theory of Steven Hobfoll. Positive verification of the first and third hypotheses confirms an important principle of the COR Theory on the investment in resources. In accordance with the principle, the acquisition of resources constitutes an essential aspect of experiencing stress because due to them, loss spirals that generates stress can be suppressed and/or compensated55,56,57. The existence of positive relationships between QoL and active coping with stress and seeking social support in stressful circumstances (positive verification of the first hypothesis) indicates that investing in resources within the aforementioned coping strategy favours an increase in QoL.

The mediating role of RSS for dependences between QoL in the adolescents and coping with stress by the use of active coping strategies and seeking social support (positive verification of the third hypothesis) confirmed implications resulting from the principle of investing in resources. Firstly, investment in resources does not serve as solely protection against loss but also increases the possibility of achieving other purposes, among other things, an increase in QoL. Secondly, the initial increase in resources (in the case analysed an increase in resources associated with active coping with stress strategies and seeking social support) contributes to gaining further benefits (among other things, of RSS) and generating loss spirals of resources benefits in this way. Their next cycles become more probable due to the increasing availability of assets and possibility of further investment. Due to the investment in resources, an individual is able to reactively cope with stress and proactively prevent stress. Thirdly, investing in resources (among other things, assets related to the preferred active coping with stress, seeking social support in stressful circumstances and receiving aid in difficult situations) favours long-lasting development of stress resilience, consequently resulting in an increase in QoL58.

Positive verification of the second hypothesis shows negative correlation between the QoL and preferred passive coping with stress in the adolescents confirms the subsequent principle of the COR Theory of the primacy of loss. In accordance with the principle, resources losses generate stress and its negative consequences in individuals. If a considerable loss or range of chronic losses occur, individuals become more sensitive to this type of experience and so they concentrate on prodromal circumstances, mainly by mechanisms typical of stress perception. If next losses are suffered, the individuals become more negatively affected by them; thus, stress surges. Loss of resources and stress experienced in a longer period of time form a type of feedback where losses of assets generate an increase in stress until PTSS occurs while a surge of stress leads to the next losses of resources59,60.

Positive verification of the fourth hypothesis saying that RSS is a mediator of dependences between QoL in the adolescents and passive coping with stress in such a way that, on one hand, it suppresses the use of passive coping with stress and on the other hand, it is positively associated with psychological QoL, is consistent with the paradox principle. The significance of the principle comes down to the situation when individuals experience losses (in the case analysed, the preference of passive coping with stress), they begin to attribute greater importance to resources benefits (in the circumstances researched, RSS). Thus, occurrence of losses motivates individuals to initiate benefits, both in order to counteract the losses suffered in the possessed resources balance as well as prevent future losses generating stress. The COR Theory underlies that the paradox principle has its own dynamics. In real or anticipated situations of losses, individuals take up activities that are subordinated to resources conservation, among other things, they aspire to minimise a negative influence of losses via reaching for external sources to gain resources that they do not have. Therefore, resilience can be said to depend on properties of external environment to a great extent. Individuals resistant to stress function in external systems that (a) are rich in different resources, among other things, personal, social, material and energetic ones; (b) enable an access to the resources; (c) provide protection against resources losses; (d) promote development of resources61.

Investing in resources allows individuals to cope with stress both proactively and reactively. Active coping strategies and social support not only address immediate stressors but also build a reserve of resources that can be drawn upon in future stressful situations, thus enhancing long-term resilience, self-efficacy and QoL. Nonactive/ passive coping strategies were associated with poorer mental health and a lower quality of life62,63,64.

Future longitudinal studies should consider tracking the long-term impact of active coping and social support on mental health and quality of life of adolescents. The subject of analysis should be the effectiveness of specific educational and preventive interventions aimed at promoting active coping strategies and seeking social support in different age groups and contexts. Understanding these mechanisms can enhance the development of targeted interventions. Further research should consider other covariates, such as psychology capital of adolescents (i.e. resilience, self-concept, self-efficacy). In addition, future studies should consider diverse populations to determine whether the findings apply to different cultural, socioeconomic and demographic groups.

Limitations

A potential weakness of the research is the use of an online form. This method of survey collection does not provide information about the respondents who choose to participate or decline to participate in the study, nor does it indicate how many of those invited actually took part. Another limitation of the study relates to the data collection method. Self-report surveys can lead to answers that contain unaddressed biases. Participants might feel compelled to give socially desirable but less truthful responses, or they may struggle to accurately assess their own situation. Another limitation concerns the psychometric properties of the research tools. A high coefficient Cronbach’s alpha suggests a homogenous test. However, a value of more than 0.90 may indicate redundancy.

Conclusions

The study empirically identifies positive relationships between QoL and coping with stress via the use of two categories of strategies in stressful situations, active coping and seeking social support. RSS is a mediator for dependences between experienced QoL and coping with stress by active coping and seeking social support. Mediating functions of RSS rely on the fact that active coping and seeking social support are positively associated with RSS from others, and in turn, translates into an increase in QoL. There is a negative dependence between QoL in the adolescents and preferred passive coping with stress. RSS is a mediator for dependences between QoL in the adolescents and passive coping with stress. Mediating roles of RSS rely on the fact that received aid, on one hand suppresses passive coping with stress, and on the other hand, is positively associated with QoL.

This is extremely important in emergency, unexpected and unknown situations like the pandemic. This period required rapid responses and specific crisis interventions. In the circumstances, a protective factor turned out to be the presence of support. Research conclusions led to the following recommendations. In the development of the adolescents, entity resources should be enhanced since they are necessary for the recognition of a difficult situation, assessment of their own capabilities and skills of using support. In education and prevention, activities promoting strategies of active coping and seeking social support should be introduced. Both in daily and difficult situations, social systems of support should be activated to provide environment for optimal development of adolescents, diminish consequences of potential risk factors, and enhance the significance of protective factors.

Investing in personal resources involves proactive efforts to build skills, seek support, engage in positive activities, and maintain health and wellness. By adopting these strategies, adolescents can enhance their resilience, manage stress more effectively, and improve their overall Quality of Life. Encouraging and supporting adolescents in these endeavors is essential for their long-term development and well-being.

Data availability

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Jones, E. A. K., Mitra, A. K. & Bhuiyan, A. R. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470 (2021).

Gayatri, M. & Irawaty, D. K. Family Resilience during COVID-19 pandemic: a Literature Review. Fam J. Alex Va. 30, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807211 (2021).

Hobfoll, S. E. Traumatic stress: a theory based on rapid loss of resources. Anxiety Res. 4, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08917779108248773 (1991).

Hobfoll, S. E. Stres, Kultura i społeczność. Psychologia i filozofia stresuGWP (2006).

Hobfoll, S. E. et al. Refining our understanding of traumatic growth in the Face of Terrorism: moving from meaning cognitions to doing what is meaningful. Appl. Psychology: Int. Rev. 56, 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00292.x (2007).

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Springer, 1984).

Baumstarck, K. et al. Coping strategies and quality of life: a longitudinal study of high-grade glioma patient-caregiver dyads. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0983-y (2018).

Saxon, L. et al. Coping strategies and mental health outcomes of conflict-affected persons in the Republic of Georgia. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 26, 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000019 (2017).

Baumstarck, K. et al. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 16, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0983-y (2018).

Saxon, L. et al. Coping strategies and mental health outcomes of conflict-affected persons in the Republic of Georgia. Epidemiol. Psychiatr Sci. 26, 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000019 (2017).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 (1985).

Babicka-Wirkus, A., Wirkus, L., Stasiak, K. & Kozłowski, P. University students’ strategies of coping with stress during the coronavirus pandemic: data from Poland. PLOS ONE. 16, e0255041. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255041 (2020).

Gurvich, C. et al. Coping styles and mental health in response to societal changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 67, 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020961790 (2021).

Kurtek, P. Prosocial vs antisocial coping and general life satisfaction of youth with mild intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 62, 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12497 (2018).

Lelonek-Kuleta, B. & Bartczuk, R. P. Online gambling activity, pay-to-Win payments, motivation to Gamble and coping strategies as predictors of Gambling Disorder among e-sports bettors. J. Gambl. Stud. 37, 1079–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10015-4 (2021).

Mudrecka, I. Wykorzystanie Koncepcji resilience w profilaktyce niedostosowania społecznego i resocjalizacji. Resocjalizacja Polska. 5, 49–61 (2013). http://libcom.linuxpl.info/resocjalizacja/archiwum/wp-content/dokumenty/streszczenia/RP%205%20(2013)%2049-61.pdf

Dijkstra, M. T. M. & Homan, A. C. Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: effective coping and Perceived Control. Front. Psychol. 7, 1415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01415 (2016).

Domínguez-Álvarez, B. et al. Children coping, Contex-e tual risk and their interplay during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Spanish case. Front. Psychol. 11, 577763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577763 (2020).

Chwaszcz, J., Łysiak, M. & Mamcarz, S. Jakość życia młodzieży w czasie pandemii COVID-19 (Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, (2022).

Sęk, H. & Cieślak, R. Wsparcie społeczne, Stres i Zdrowie (Wyd. Nauk. PWN, 2004).

Niewiadomska, I. Mechanizmy generujące Wielowymiarowe Wsparcie Rodzicielskie w Warunkach Stresu wywołanego Przez pandemię COVID-19. Analiza zależności wynikających z Poszerzonego Modelu Dopasowania zasobów Stevana Hobfolla (Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2022).

Ron, P. & Ron, A. The relationships between on-going terror attacks, military operations and wars and the well-being of jewish and arab three generations civilians in Israel. Zeszyty Pracy Socjalnej. 2, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.4467/24496138ZPS.17.003.6538 (2017).

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B. & Valentine, J. D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult Clini Psychol. 68, 748–766. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748 (2000).

Hobfoll, S. E. Social and Psychological resources and Adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 6, 307–324 (2006).

Norris, F. H., Baker, C. K., Murphy, A. D. & Kaniasty, K. Social support mobilization and deterioration after Mexico’s 1999 flood: effects of context, gender, and time. Am. J. Community Psychol. 36, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-005-6230-9 (2005).

Hobfoll, S. E. et al. Trajectories of resilience, resistance, and distress during ongoing terrorism: the case of jews and arabs in Israel. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 77, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014360 (2009).

Hobfoll, S. E., Tracy, M. & Galea, S. The impact of resource loss and traumatic growth on probable PTSD and depression following terrorist attacks. J. Trauma. Stress. 19, 867–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20166 (2006).

Hall, B. J. et al. Loss of social resources predicts incident posttraumatic stress disorder during ongoing political violence within the Palestinian Authority. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 50, 561–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0984-z (2015).

Fang, S., Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L. & Krahn, H. J. Convoys of perceived support from adolescence to midlife. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 1416–1429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519899704 (2020).

Luthar, S. S., Ebbert, A. M. & Kumar, N. L. Risk and resilience during COVID-19: a new study in the Zigler paradigm of developmental science. Dev. Psychopathol. 33, 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001388 (2021).

Wang, M. T. et al. The roles of stress, coping, and parental support in adolescent psychological well-being in the context of COVID-19: a daily-diary study. J. Affect. Disord. 294, 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.082 (2021).

Wang, L., Yang, L., Di, X., Dai, X. F. & Support Multidimensional Health, and living satisfaction among the Elderly: a case from Shaanxi Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228434 (2020).

Bi, S. et al. Perceived Social Support from different sources and adolescent life satisfaction across 42 Countries/Regions: the moderating role of National-Level Generalized Trust. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 1384–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01441-z (2021).

Feinberg, M. E. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parent, child, and Family Functioning. Fam Process. 61, 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12649 (2022).

Cao, S. et al. Age Difference in roles of Perceived Social Support and Psychological Capital on Mental Health during COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 13, 801241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.801241 (2022).

Carroll, N. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 12, 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352 (2020).

Gadermann, A. C. et al. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open.11, e042871. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871 (2021).

Zhu, S., Zhuang, Y. & Ip, P. Impacts on children and adolescents’ lifestyle, Social Support and Their Association with negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 4780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094780 (2021).

Hussong, A. M. et al. COVID-19 life events spill-over on Family Functioning and Adolescent Adjustment. J. Early Adolesc. 42, 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/02724316211036744 (2022).

He, M. et al. Family Functioning in the time of COVID-19 among economically vulnerable families: risks and protective factors. Front. Psychol. 12, 730447. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.730447 (2021).

Cabrera, N. J. et al. Cognitive stimulation at home and in child care and children’s preacademic skills in two-parent families. Child Dev. 1, 1709–1717. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13380 (2020).

Eales, L. et al. Family resilience and psychological distress in the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. Dev. Psychol. 57, 1563–1581. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001221 (2021).

Gregus, S. J. et al. Parenting & children’s psychological Adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. School Psychol. Rev. 51, 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1880873 (2022).

Sosa Díaz, M. J., Emergency Remote & Education Family support and the Digital divide in the context of the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 7956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157956 (2021).

Dalton, L., Rapa, E. & Stein, A. Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. Lancet. Child. Adolesc. Health. 5, 346–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097-3 (2020).

Thomson, K. C. et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Family Mental Health in Canada: findings from a multi-round cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 12080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph1822-1208 (2021).

Woźniak-Prus, M. et al. Positive experiences in the parent-child relationship during the COVID-19 lockdown in Poland: the role of emotion regulation, empathy, parenting self-efficacy, and social support. Fam Process. 63, 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12856 (2024).

Garcia de Avila, M. A. et al. Children’s anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory study using the children’s anxiety questionnaire and the Numerical Rating Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 5757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165757 (2020).

Mariani, R. et al. The impact of coping strategies and Perceived Family support on depressive and anxious Symptomatology during the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) Lockdown. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 587724. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.587724 (2020).

Ravens-Sieberer, U. The Kidscreen Questionnaires Quality of life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Handbook (Pabst Science, 2006).

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. & Weintraub, J. K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267 (1989).

Juczyński, Z. & Ogińska-Bulik, N. Tools for Measuring Stress and Coping with Stress (Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego, 2012).

Schulz, U. & Schwarzer, R. Soziale Unterstützung Bei Der Krankheitsbewältigung: die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS). Diagnostica. 49, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924.49.2.73 (2003).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instruments Computers. 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553 (2004).

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P. & Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 (2018).

Niewiadomska, I. & Jurek, K. Mechanizmy regulujące Wsparcie psychologiczno-pedagogiczne w Czasie Pandemii COVID-19. Analiza zależności Wynikajacych z Zasad Teorii Zachowania zasobów Stevana Hobfolla (Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2022).

Niewiadomska, I. et al. PTSD as a moderator of the Relationship between the distribution of Personal resources and spiritual change among participants of hostilities in Ukraine. J. Relig. Health. 62, 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01547-z (2023).

Chen, S., Westman, M. & Hobfoll, S. E. The Commerce and crossover of resources: Resource Conservation in the service of Resilience. Stress Health. 31, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2574 (2015).

Heath, N. M. et al. Reciprocal relationships between resource loss and psychological distress following exposure to political violence: an empirical investigation of COR theory’s loss spirals. Anxiety Stress Coping. 25, 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.201 (2012).

Hou, W. K. et al. Everyday life experiences and mental health among conflict-affected forced migrants: a meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 264, 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.165 (2020).

Hobfoll, S. E., Stevens, N. R. & Zalta, A. K. Expanding the Science of Resilience: conserving resources in the aid of adaptation. Psychol. Inq. 26, 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840 (2015).

Stang-Rabrig, J. et al. Students’ school success in challenging times: importance of central personal and social resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 1261–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00739-9 (2024).

Vallejo-Slocker, L. et al. Mental Health, Quality of Life and coping strategies in vulnerable children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psicothema. 34, 249–258. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2021.467 (2022).

Orban, E. et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1275917. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1275917 (2024).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jurek, K., Niewiadomska, I. & Chwaszcz, J. The effect of received social support on preferred coping strategies and perceived quality of life in adolescents during the covid-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 21686 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73103-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73103-6