Abstract

The disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food supply has underscored the need for localized household assessments of food insecurity, particularly in developing countries where such data may be limited. Consequently, this study aims to assess the economic access to food for Chilean households in the pre- and post-pandemic scenarios. We utilized an Almost Ideal Demand System, leveraging Household Consumption Surveys to estimate the cross and own expenditure elasticities among food categories. And, to gauge the potential impact of prices on food security the quantities of food that households acquired were nutritionally scored by income quintile. Our findings pre- and post-pandemic revealed a prioritization of Meats, Grains & Cereals and Fruit & Vegetables across all households, irrespective of their socioeconomic quintile. Moreover, post-pandemic is observed a tendency towards lower-income households experiencing a higher price increment than higher-income households (p-value < 0.0001). The implementation of social protection policies, plus the articulation of agrarian, food and nutritional policies, is observed as vital for addressing food insecurity and alleviating poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2022 over 3.1 billion people could not be able to afford a healthy diet. This unaffordability of a healthy diet is driven by income inequality and causes different degrees of food insecurity in all regions of the world [1]. Food security has been defined as an integrated approach based on food availability, economic access, utilization of nutrients, and stable food supply [2]. Food systems face the challenge of providing affordable and nutritious foods in a climate change context. Over recent decades, a paradigm shift from resource-driven growth to a productivity-driven growth has improved agricultural production, particularly in developing nations, where enhanced productivity accounted for 60% of the overall agricultural growth observed over the past half-century [3]. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic placed unprecedented strain on global food supply chains and domestic economies, thereby accentuating the critical need for localized assessment due to the scarcity of microeconomic studies regarding food security in emerging economies [4].

Assessment of food security is complex due to its multifaceted nature. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) was developed as a measure of either households or individuals that aims to produce cross-cultural comparable annual estimates of food security [5]. It has been validated as a valuable tool in Sub-Saharan Africa [6] and Latin America and the Caribbean [7]. However, it is constraint in elucidating the root causes of food insecurity, the relationship of the household consumption decisions and the dynamic food prices, and the household’s resilience when confronted with rising food costs. Hence, there has been recognition of the necessity to adopt a comprehensive assessment of food security, that incorporates quantitative and qualitative dimensions. This multifaceted perspective is grounded in the relationship between economic access to food and indicators such as food prices, household expenditure elasticities of demand, and total household food budget [6, 8].

Chile, classified as a developing country, is considered as one of the strongest states in Latin America, despite its relatively low levels of income redistribution. Over the period spanning from 1964 to 2017, household income dynamics in Chile reveal a trend of subdued growth in the lower quintiles in contrast to the more pronounced expansion of household income within the top 1%, as evidenced by fiscal income series [9]. While in nutrition, a diminishment of undernutrition from 15.5% in 1975 to 5.0% in 1995, along lower prevalence of low birth weight and undernourished mothers, show the rapid nutrition transition that occurred in Chile. This improvement in malnutrition has been attributed to implementation of public policies, such as the Day Care Food Program (JUNJI) for preschool children and the Food School Program (PAE), which catered to over 660,000 children by the year 2000. Nevertheless, Chile faces emerging nutritional challenges, including a a rise in overweight and obese pregnant woman, increased obesity rates among children under five years old, and a growing prevalence of obesity among men and women, with 74.2% of the population classified as overweight or obesity by 2017 [10, 11]. Despite the low prevalence of undernourishment in Chile, moderate to severe food insecurity continues to affect vulnerable social groups. Pre-pandemic studies have identified differential patterns of expenditure across household income levels in Chile, with lower own-price elasticities observed in certain food groups among lower-income households [12]. Therefore, our study aims to assess the economic accessibility and nutritional quality for Chilean households in a pre-pandemic (2016–2017) and post-pandemic (2021–2022) scenarios, with a particular focus on income quintiles. Additionally, we seek to estimate both the own and cross-price elasticities among different food categories, thereby creating a model to predict the potential impact of household nutrient acquisition over price fluctuations. And to compare our findings within global and regional context.

2 Materials and methods

According to FAO [1], food security is the right of all persons to have adequate physical, economic and safe access to meet their nutritional needs. Assessing economic access to a nutritional basis requires accounting for household size when analyzing the multivalued treatment effect. This study, therefore, measures economic access to food through a multidimensional framework encompassing food expenditure in terms of prices and households demand, nutritional quality of diets, and dietary diversity.

Food expenditure highlights spending patterns and financial constraints for food [13], whereas nutritional quality of diets serves as a reliable indicator of food security [14]. Plus, limited dietary diversity is a significant contributor to imbalanced nutrition [15].

2.1 Data sources

Comprehensive data on cross-sectional research pertaining to household expenditure and prices were sourced from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Chile (INE). Reported household expenditure values represent the monthly expenses codified as specific item categories over a 12-month period, collected from a representative, two-stage, stratified sample (based on geographic area and socioeconomic classification) of urban households from the capital cities. These expenditures were documented as individual expenses surveyed, collecting the data of household socioeconomic characterization, quantity acquired, and expenditure amount. The socioeconomic quintiles defined by INE [16] in the Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares (EPF) surveys were structured to accommodate an equal number of households, organized in ascending order based on their respective income levels. Quintile I encompasses households with the lowest monthly income, while quintile V comprises households with the highest. The data from Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares (EPF) surveys was harmonized on a population basis, which encapsulated budgetary expenditures of Chilean households by quintiles of the year 2006 (VI EPF), 2011 (VII EPF), 2016 (VIII EPF) and 2021 (IX EPF) [16]. The characteristics of households per income quintile for each year is provided in Table 1.

For further economic and nutritional assessments under a pre-pandemic and post-pandemic scenarios, we analyzed individual household surveys from 2016 (VIII EPF) and 2021 (IX EPF), harmonizing them in terms of quantity units (kg, g, L, ml). Household food expenses were classified into eight types: raw & processed foods, restaurant, non-alcoholic drinks, alcoholic drinks, prepared foods, food service, vending machine and unspecified food expenses. The category raw & processed foods, was further divided into eight food categories, subcategorized in 63 specific food groups for harmonization.

We included the categories of raw and processed foods, prepared foods, non-alcoholic drinks, and alcoholic drinks for subsequent analysis, as these categories had their quantities recorded in the surveys and were acquired for household consumption. Survey entries from these four categories from the VII EPF (2016–2017) and the IX EPF (2021–2022) were considered for the economic and nutritional analysis of the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic scenarios. Additional specifics regarding survey entries grouped food categories and subcategories, original EPF survey descriptors, subcategory CPI baseline prices and their inclusion for economical and nutritional analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

2.2 Food categories expenditure share and price

The expenditure share (Shares,c,q) for each food category and household combination was calculated using equation [1].

where Shareh,c is the total percentage of expenditure share of the h household for the n products of the c food category, Expenditureh,c,i is the expenditure of the h household for the i item, and Household expenditure is the total expenditure for all food categories for the h household. And a weighted price (Priceh,c) for each household and food category was calculated using equation [2].

where Priceh,c is the weighted price of the h household for the n products of the c food category, Expenditureh,c,i is the expenditure of the h household for the i item, Quantity h,c,i is the quantity the h household acquired of the i item, and Expenditureh,c is the total expenditure of the h household for the n products of the c food category. For comparison, the average price paid by households and the share of expenditure was determined for each food category, income quintile and EPF survey combination. These values were calculated using the individual expenditure surveys and expressed as real prices, adjusted to the CPI of May 1st, 2024. Then, all monetary values were converted to US dollars, using the exchange rate from September 2021, set at CLP$783.63. Following the methodology of [17], a Jonckheere–Terpstra test was conducted among income quintiles to assess increasing or decreasing trends of expenditure, price and variations between the pre-pandemic and the post-pandemic scenarios.

2.3 Nutritional quality

Nutritional quality was assessed for each food item by referencing a specific item, obtaining detailed information on calories and macro-nutrients content, as elaborated in Supplementary Table 2. Quantities were expressed in terms of 100 g portions of available nutrients after cooking for meats, legumes and cereals & grains. The gram equivalents were calculated following [18] using equation [3]. For liquids, the density in grams per cubic centimeter (g cm−3) was used as conversion factor, and a factor of 1 was used for solid foods.

Subsequently, the daily per person energy and protein requirements were then compared to the recommended dietary intake guidelines. For adult males, these guidelines stipulate a daily requirement of 2300 kcal and 56 g of protein, while for adult females, the recommended daily intake is 1900 kcal and 46 g of protein, in accordance with the guidelines from [19].

2.4 Demand analysis and economic access to food

In line with established methodologies for assessing household demand from [20], we applied the Almost Ideal Demand System (AIDS) econometric model developed by [21]. This model was fitted independently to the households weighted prices (Priceh,c) and expenditure shares (Shareh,c) of each quintile. The fitting of the AIDS model was carried out using the R package micEconAids, following the guidelines provided by [22]. The AIDS model is a preferred choice for empirical demand analysis in microeconomics due to its functional conformity with known household-budget data, it adheres the consumer theory, effectively mitigates specification biases inherent in various demand systems, and enables the simultaneous examination of consumption patterns across multiple goods [23]. The specific formulation of the fitted AIDS model is detailed in equation [4].

where wi is the share of total expenditure for the ith food category, Pj is the price of the jth food category, X is the total expenditure, T is the Törnqvist price index, and α, β and γ are model coefficients.

We employed the uncompensated (Marshallian) expenditure elasticity of demand to model changes in the quantity of a specific product demanded by households in response to variations in the product’s own price and prices of related products, as outlined in [23]. By scrutinizing the quantities that households can afford under a given combination of income and food prices vectors, in order to maximize the household utility. This analysis entailed estimating cross-price and own-price uncompensated expenditure elasticities for the four food classes that were further examined over the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic scenarios, utilizing the fitted AIDS model. Analyses were conducted using R version 4.0 utilizing the micEconAids package.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline of the household food expenditure

The EPF surveys included 10,092 households in 2006, 13,056 in 2011, 15,168 in 2016 and 14,989 in 2021. The surveys show consistent trends pre- and post-pandemic in food expenditure rankings. Raw & processed foods account for over 60% of the total expenses (Table 2), followed by restaurant expenditures (14.4–19.4%), non-alcoholic drinks (5.0–6.6%), and prepared foods (2.5–6.9%). Unspecified food expenses ranged from 0.6% to 8.3% (Table 2). On average, restaurant expenditures constituted a larger share of total food expenditure in the highest-income households (26.7%) compared to the lowest-income households (8.6%). In contrast, raw & processed foods made up 51.9% of highest-income households’ food expenditure, but 74.3% of the lowest-income households. This suggests that assessing food security should focus on raw & processed foods, particularly in lower-income households.

3.2 Household raw and processed food sources by income

Monthly expenditures on raw and processed foods by income quintile from 2006 to 2021 showed stable purchasing patterns (Fig. 1), where Meats consistently commanded the largest share of households food budgets regardless of income quintile, ranging from 25.1% to 26.4%.

As household income increased, there was a noticeable reduction in the proportion of budget allocated (Table 3) to Cereals & grains (p-value = 0.0073), and, to a lesser extent, Fruits and vegetables (p-value = 0.0071). In contrast, higher-income households allocated a larger share to Dairy and eggs (p-value = 0.0089), Other foods (p-value = 0.0073), Processed fruits and vegetables (p-value = 0.0076), and Fish & seafood (p-value = 0.0105). While Fats & oils showed uniform spending across quintiles, with higher-income households allocating a smaller share (p-value = 0.0084). These differences suggest that higher-income households purchase a broader diversity of foods. Nevertheless, Meats, Cereals & grains, and Fruits & vegetables remain the primary components of food expenditures, regardless of household income.

3.3 Pre and post pandemic household food purchases by income

Table 3 compares pre- and post-pandemic household food expenditure by income quintile. Generally, lower-income households spent less across all categories (p-value < 0.0001), but the spending gap between lower- and higher-income households narrowed post-pandemic. Pre-pandemic, quintile I spent 44% of what quintile V spent on raw & processed foods, rising to 50% post-pandemic.

To inspect if either changes in food prices or increased government monetary support during the pandemic were the cause, pre- and post-pandemic food prices by quintile were assessed (Table 4). It was observed that higher-income households consistently paid more for food than lower-income households (p-value < 0.0001). However, lower-income households experienced a greater price increases (p-value < 0.0001)., contributing to narrowing the expenditure gap, as lower-income households had to pay disproportionately more to access similar quantities of food post-pandemic. In contrast, higher-income households reduced spending on non-priority categories like non-alcoholic drinks and processed fruits & vegetables (Table 4). The only exception to this trend was prepared foods, where prices may be influenced by a shift towards purchasing family-sized portions rather than individual servings. These findings underscore the importance of considering both food prices and income when addressing equitable food access in Chile.

3.4 Demand analysis of the household food expenditure pre and post pandemic

The matrix of own and cross expenditure elasticities of demand resulted in 11 × 11 matrix for each quintile (Supplementary Table 3). Own expenditure elasticities are shown in black on the diagonals. Positive values show a proportional increase in household expenditure in response to a price increase, while negative values indicate a reduction. Among the highest-budget food categories, Cereals & grains and Fruits & vegetables have unitary own elasticities across all income levels. Meats, however, exhibit inelastic behavior, with values ranging from − 0.63 to − 0.87, being more inelastic in lower-income households. This suggests Meat is a baseline food in Chilean households (Fig. 1). Dairy & eggs and Non-alcoholic drinks also show unitary own elasticity, reflecting their importance across all income quintiles. Conversely, Alcoholic drinks are the most inelastic, with elasticities ranging from 0.01 to − 0.67.

Cross-expenditure elasticities of demand show proportional changes in food budget allocation when prices of other food categories rise. For key categories like Cereals & grains, Meats, and Fruits & Vegetables high cross-elasticities of demand are observed with Processed fruits & vegetables, Fish & seafood, Fats & oils, Other foods, and Alcoholic drinks, ranging from − 0.81 to 0.48. While cross-elasticities within the three staple categories themselves are small, ranging from − 0.17 to 0.11.

These results suggest households reduce spending on less essential foods when prices rise for staples like Meats, Cereals & grains, and Fruits & Vegetables. This behaviour limits food diversity, as there is no compensation for Meats with protein sources such as Fish & seafoods or Dairy & eggs.

3.5 Pre and post-pandemic analysis of the nutrients consumed within the household

Analysis of nutrients from household monthly acquisitions pre- and post-pandemic (Table 5) reveals a trend of reduced acquisition across all income levels after the pandemic. However, due to smaller household sizes, kilocalorie availability per person has increased, narrowing the gap between quintiles I and V.

Calories and proteins generally meet the majority of recommended daily intakes based on household size, regardless of quintile. Pre-pandemic, households provided 78% to 87% of daily calorie needs for men, increasing to 83–87% post-pandemic. For woman, 95–105% of daily needs were met pre-pandemic, increasing to 100–106%, post-pandemic. Considering that out-of-home food expenses account for over 25% of total food expenditure, nutritional requirements are exceeded for both men and women.

High variability is observed in acquisition patterns within quintiles (Supplementary Table 4). Prepared foods show the greatest socioeconomic gap, with 77% of higher-income households acquiring these foods compared to only 34% of lower-income households. This is reflected in the amount of fats acquired, increasing from 33 g per 1000 kcal in quintile I to 39 g per 1000 in the quintile V.

Among Raw & processed foods, Grains & Cereals category were acquired by over 98% of households, followed by Fruit & Vegetables (over 88%) and Meats (over 87%). While Cereals & Grains are the second most acquired category, they account for 29–42% of kilocalories for the highest- and lowest-income households, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). Meats, despite moderate acquisition amounts (6 to 12 kg per household per month), contribute significantly to calorie intake (10–13%) and proteins (34–39%). Similarly, Fruits & Vegetables contribute 10–13% of caloric intake, with 24 to 36 kg per household monthly. All other food categories, contributed less to the diet but had a higher proportion across all categories in the highest-income households.

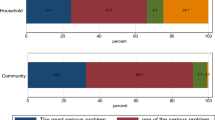

A comparison of subcategories (Fig. 2) shows consistent acquisition patterns both pre- and post-pandemic, with fresh vegetables, bread, fresh fruits, chicken and beef being the top items, in that order. Prices increases did not disrupt these trends (Table 4). Interestingly, higher-income households allocate more to beef and processed meats, while lower-income households prioritize chicken. In the Fruit & Vegetables category, higher-income households showed a preference for fresh fruits over fresh vegetables, whereas lower-income households opt for more fresh vegetables. And also, higher-income households tended to purchase less bread compared to lower-income households. Pasta and rice exhibit consistent acquisition across all quintiles, with 1.9–2.3 kg of rice and 1.5 kg of pasta acquired monthly, while legumes are less acquired with 0.80–0.86 kg, both pre- and post-pandemic. This stability underscores the importance of these staples in household diets.

4 Discussion

4.1 Household food expenditure and diet quality in Chile within regional and global contexts

This study in Chile highlights significant differences in household food budgets, with the highest-income households allocating 18% to food and the lowest-income households 67%. This trend, first reported by Deaton and Paxton [24] in their examination of household expenditures by income level in countries such as the United States, Great Britain, France, Taiwan, Thailand, Pakistan and South Africa, has also been observed In New Zealand [25], and Canada [26]. In Latin America, similar patterns are evident; for instance in Colombia, the proportion of spending on food decreases as household income increases [27], while in Peru, higher-income households doubled the food expenditure of lower-income households, ranging among income levels from 35 to 49% [28]. In Brasil, the proportion of food expenditure is most significant among lower-income households, ranging among incomes from 15 to 25% [29].

In developed economies, only a minority of households allocate more than one-third of their budget to food, whereas, in Latin America, the food expenditure proportion is significantly higher, reflecting substantial disparities in economic access to food and aligning with traditional definitions of poverty, as begin unable to afford the basic needs of food, clothing and shelter [30]. In this context, where food insecurity and poverty intersect, Chile and Uruguay stand out with Global Hunger Index (GHI) [31] scores below 5, contrasting with the regional average of 8.6. Neighboring countries such as Peru (7.2), Colombia (7.0), and Brazil (6.7) also exhibit medium low GHI scores. This is supported by the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 report from FAO [1], where Chile maintains the lowest prevalence of undernourishment in the region (< 2.5%); the report also notes that 3.7% of Chile’s population experiences severe food insecurity, a figure considerably lower than Brazil's 6.6%, Colombia's 5.3% and Peru’s 20.3%, despite the differences in household food allocation proportions among income quintiles. At the same time, Chile faces the region’s highest obesity prevalence at 38.9%, far exceeding Brazil (28.1%), Peru (27.1%), and Colombia (23.6%), indicating a complex dual burden of malnutrition that involves food and nutritional security.

Food expenditure, while informative, does not directly equate to nutritional security, as purchased foods by a household may not necessarily constitute a healthy diet. The cost of a healthy diet, defined by FAO [1] as the expense in purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars of locally available foods meeting energy and nutritional guidelines, is highest in Latin America and the Caribbean, averaging 4.56 PPP in 2022. In the present study, household food expenditure per capita in Chile for Raw & processed foods was found to range from 2.03 to 3.07 dollars across income quintiles in 2016 and from 3.65 to 4.69 dollars in 2021. These expenditures remain below the cost of a healthy diet reported for Chile in 2017 (3.38 dollars) and 2021 (3.86 dollars); however, they are higher than the 2021 cost of a healthy diet in Northern America and Europe, which averaged 3.12 dollars per capita [1]. This disparity raises questions about the affordability and accessibility of a healthy diet in Chile, despite the country’s comparatively favorable food security indicators and high amount of agricultural exportations. And underscores the need for targeted public policies to enhance food and nutritional security across Latin America and the Caribbean, despite being this region the world’s leading net food-exporting area, with exports totaling USD$3.49 billion in 2022 and contributing 15.5% to global food production[32].

However, our findings reveal higher cross-elasticity values in higher-income households, contrasting with studies like [25], which reported higher cross-elasticities in lower-income quintiles in New Zealand. These differences may stem from variations in households incomes, food prices and cultural preferences, as higher-income households in Chile, like in the U.S., tend to pay higher prices and acquire larger quantities of food [17]. And also, to certain food groups being considered basic subsistence [12], as in this case, lower cross-elasticities, in contrast to their undesirability in standard economy, are a sign of nutritional stability, since nutritional status is not greatly modified by price increases [30].

The study also identified a core food basket prioritized by households, with Meats, Grains & Cereals and Fruit & Vegetables as key components, irrespective of income level. This contrasts with findings from Canada [33] and the United States [34], where lower-income households tend to purchase fewer Fruits & Vegetables and dairy products. In Chile, however, Fruits & vegetables and Meats are preferred across all income levels, reflecting their prominence in traditional recipes. As a result, maintaining the affordability and accessibility to the local diversity of these staples becomes not just an economic necessity but also a matter of cultural significance. The stability of staple food prices is therefore critical for ensuring both food and nutritional security, and dietary diversity. While higher-income households purchase a wider variety of foods, such as dairy & eggs, and fish & seafood, they also allocate a larger proportion of their budget to non-essential items, like snacks, ice cream, and chocolates, suggesting that higher spending does not necessarily equate to healthier diets. It is important to note that this study assessed food purchases without delving into the actual consumption, requiring further analysis to evaluate diet quality, including meals outside the home. Moreover, the diverse food acquisition patterns complicate classification of healthy diets, as around 8% of households do not acquire Fruits & Vegetables, and 56% do not purchase Fish & Seafood.

4.2 Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security

The COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on food security are complex and vary by socioeconomic status, location, and food items considered [35]. Vulnerable communities, especially those with low incomes, already faced barriers to accessing resources, making them more susceptible to the pandemic’s impact. Additionally, rising food inflation, a trend observed in the region since 2019, was further exacerbated by the pandemic, reducing households' purchasing power. This jeopardized their food security and limited their access to nutritious foods, especially those among the lowest income quintiles, who allocate a significant proportion of their budget to food purchases [36]. Furthermore, disparities in diet-related chronic diseases were exacerbated during the pandemic, with higher incidences reported among racial and ethnic minorities, as well low-income populations [37].

Our study shows that lower-income Chilean households experienced greater price increases post-pandemic, accompanied by a rise in food expenditure on Meats, Cereals & grains, and Fruit & vegetables. Similar trends were observed in Mexico, where post-pandemic relative amount of purchases of meats, fruits, vegetables and tortillas increased among lower-income households [38]. Economic access to food is expected to further decline as prices rise, placing increased stress on households, and leading to more vulnerability to poverty among the population [39]. However, this study suggests that socioeconomic differences play a significant role in purchasing patterns, with lower-income households spending proportionally more on basic foods like Meats, Fruits & Vegetables and Cereals and Grains, despite their proportional allocation to baseline foods is higher than of higher-income households (Fig. 1).

4.3 Policy impacts on food security in the context of Latin America

In Chile, public policies have significantly impacted food security [11]. The School Feeding Program (PAE), managed by JUNAEB, benefited over 1.5 million schoolchildren and 180,000 preschoolers from lower-income households by 2017, covering 60% of the target population [40]. While the Higher Education Food Grant (BAES) supports over 500,000 higher education students from the 60% of households with the lowest incomes, providing to each student USD$57 per month for food purchases in 2024 by Resolution Exempt N°351/2018 of the Ministry of Education of Chile. Furthermore, the National Complementary Feeding Program (PNAC) distributes 10.5 million kg of food annually to children under six years old, low-birthweight infants and/or born before 32 weeks of pregnancy, expectant and nursing mothers, and children and adolescents with metabolic disorders. And, the National Complementary Feeding Program for Seniors (PACAM) distributes 11 million kg of food annually to 461,321 seniors, covering 31.6% of the eligible population [41]. This program provides 1 kg of powder vegetable cream soup and 1 kg of powdered milk drink, equating to a monthly nutritional contribution of 3,960 kcal and 130 g of proteins for the vegetable cream soup as per Resolution N°416/2013 from the National Central Supply (CENABAST), and 4,000 kcal and 180 g of proteins for the milk drink [42]. These programs have contributed to Chile’s low food insecurity rates in the region [1]. However, new measures are urgently needed to address overnutrition, emphasizing both physical and economic access to a healthy diet.

In response to the pandemic, the Chilean government, like others, implemented social protection measures to safeguard food security for vulnerable populations. Key among these was the ‘‘Apoyo Canasta Básica”, a subsidy to offset rising food costs. International experiences highlight the variable impact of similar measures. For example, in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) card allowances by 15% under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) reduced spending on food away from home by 22% and increased food at home spending by 8%, whereas the Pandemic-Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBTs) program led to a 9% increase in spending on food away from home and a 3% decrease in food at home spending, associated to lower nutritional quality as food away from home tends to contain more calories and nutrients of public health concern. While charitable food receipts, food vouchers tradeable for food at food banks, showed positive impacts by reducing food away from home spending by 9% and increasing food at home spending by 3%, and important role during the pandemics, as food distribution from food banks expanded 26% [37].

In Ecuador, a pre-pandemic intervention involving cash assistance, food vouchers, and direct food transfers proved to improve food access but had varied impacts. Household with calorie intake per capita below 2100 kcals benefited the most from direct food transfers, due to households saving a significant amount of the cash, while food vouchers were the most cost-effective intervention for improving dietary diversity due to the protection against rising prices, and the lack of the logistics costs of direct food transfers [43]. These experiences underscore the importance of tailoring food security policies to target populations and integrating food relief measures into broader programs with consistent impact monitoring.

Public policies on food security have traditionally emphasized food assistance programs; however, contemporary challenges such as obesity, rural-to-urban migration, and gentrification require a shift focus towards comprehensive strategies, including enhanced food labeling regulations and updated dietary guidelines. Chile’s 2012 Law 20.606 marked significant progress in food labeling reform, while Mexico’s Official Norm NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010 of 2020 and Colombia’s Law N° 2120 of 2021 have similarly aimed to promote informed food choices. Despite these advances, contemporary challenges requires policies that integrate agrarian and food policies.

Peru's response to the 2008 food crisis exemplified this alignment. By fostering family farming (Agricultura Campesina, Familiar y Comunitaria), its primary source of food production, the country enhaced its local agricultural systems, institutionalizing these efforts through Law Nº 31,315, the Food and Nutritional Security Act [44]. Similarly, Colombia’s Law 1876 of 2019 established the National Agricultural Innovation System and the National Comprehensive Assistance Plan to support family farming and improve market access for rural producers (Economia Campesina, Familiar y Comunitaria), and reinforcing the role of the Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA) [45]. In Chile, despite the longstanding existence of agricultural innovation (INIA) and extension (INDAP) institutions, founded in the 1960’s, as well as the contribution of family farming (Agricultura Familiar Camepsina e Indígena) to food production, it was not until 2022 that the Estrategia Nacional de Soberanía para la Seguridad Alimentaria was introduced, providing a strategic framework for the country. This alignment is important, as agriculture plays a fundamental role in ensuring food production and stability in prices, food and nutritional security, and poverty reduction by generating employment and income in rural communities.

5 Conclusion

Overall, significant disparities in household food expenditure and economic access to food are evident across incomes quintiles in Chile. Lower-income households allocate a larger proportion of their budgets to staple foods like cereals, meats and fruits & vegetables, while higher-income households spend more on non-essential foods. Post-pandemic, lower-income households experienced greater price increases, narrowing the spending gap but without improving dietary diversity, despite government financial support. These findings highlight the importance of targeted policies that address both economic access to essential foods and the persistent nutritional challenges faced by vulnerable populations in Chile. Agricultural production and prices of cereals, meats and fresh fruits & vegetables likely play a critical role in influencing food security. Public policies that integrate agrarian, food and nutritional security have the potential to contribute to reducing poverty in its classical interpretation.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available at INE repository, https: //www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/sociales/ingresos-y-gastos/encuesta-de-presupuestos-familiares.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

FAO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024. State Food Secur Nutr World. 2024. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en.

Clapp J, Moseley WG, Burlingame B, Termine P. Viewpoint: the case for a six-dimensional food security framework. Food Policy. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102164.

Hailu G. Reflections on technological progress in the agri-food industry: past, present, and future. Can J Agric Econ. 2023;71(1):119–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12325.

Bloem JR, Farris J. The COVID-19 pandemic and food security in low- and middle-income countries: a review. Agric Food Secur. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-022-00391-4.

FAO. Voices of the Hungry. Methods for estimating comparable prevalence rates of food insecurity experienced by adults throughout the world. Rome; 2016.

Wambogo EA, Ghattas H, Leonard KL, Sahyoun NR. Community and global nutrition validity of the food insecurity experience scale for use in Sub-Saharan Africa and characteristics of food-insecure individuals. Curr Dev Nutr. 2018;2(9):062.

Smith MD, Rabbitt MP, Coleman- JA. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the food and agriculture organization’s food insecurity experience scale. World Dev. 2017;93:402–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.006.

Melgar-Quinonez HR, Zubieta AC, MkNelly B, Nteziyaremye A, Gerardo MFD, Dunford C. Household food insecurity and food expenditure in Bolivia Burkina Faso, and the Philippines. J Nutr. 2006;136(5):1431S-1437S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.5.1431S.

Flores I, Sanhueza C, Atria J, Mayer R. Top incomes in Chile: a historical perspective on income inequality, 1964–2017. Rev Income Wealth. 2020;66(4):850–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12441.

Margozzini P, Passi A. Encuesta Nacional de Salud, ENS 2016–2017: un aporte a la planificación sanitaria y políticas públicas en Chile. ARS Medica. 2017;43(1):30–4.

Vio F, Albala C. Nutrition policy in the chilean transition. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3(1):49–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980000000070.

Caro J. Designing a tax to discourage unhealthy food and beverage purchases: the case of Chile. Food Policy. 2017;71:86–100.

Jayaweera R, Verma R. Food security: the impact of migrants and remittances in Sri Lanka. Discover Food. 2024;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-023-00070-8.

Hoddinott J, Yohannes Y. Dietary Diversity as a Household Food Security Indicator. Washington DC; 2002.

Jayawardena R, Byrne NM, Soares MJ, Katulanda P, Hills AP. Food consumption of Sri Lankan adults: an appraisal of serving characteristics. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(4):653–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012003011.

INE. Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares. 2023. https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/sociales/ingresos-y-gastos/encuesta-de-presupuestos-familiares. Accessed 25 Dec 2024.

French SA, Wall M, Mitchell NR. Household income differences in food sources and food items purchased. Int J Behav Nutr Physical Activity. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-77.

Kohl J, Hohberg V, Hauff P, Lang C, Faude O, Gollhofer A, et al. Development of a metric healthy eating index-2015 and comparison with the healthy eating Index-2015 for the evaluation of dietary quality. Front Nutr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.952223.

US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture; 2010.

Wessells C, Wilen J. Seasonal patterns and regional preferences in Japanese household demand for seafood. Can J Agric Econ. 1993;42:87–103.

Deaton A, Mullenbauer J. An almost ideal demand system. Am Econ Rev. 1980;70(3):312–26.

Henningsen A. Demand analysis with the “almost ideal demand system”. R package micEconAids. R-project. 2017.

Ng CS, Au M, Ma R, Leung JYY, Quan J. The impact of alcohol pricing policies on public health in Hong Kong, China: a modelling study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;26: 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100510.

Deaton A, Paxson C. Economies of scale, household size, and the demand for food. J Polit Econ. 1998;106(5):897–930. https://doi.org/10.1086/250035.

Ni Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Schilling C, Yang Q, Kaye-Blake W, Genç M, et al. Food prices and consumer demand: differences across Income levels and ethnic groups. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10): e75934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075934.

Ricciuto L, Tarasuk V, Yatchew A. Socio-demographic influences on food purchasing among Canadian households. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(6):778–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602382.

Torres PG. ¿En qué gastamos para comer y cuánto? condiciones socioeconómicas y presupuesto para el consumo de alimentos (Colombia, 1993–2014). Revista Colombiana de Sociología. 2019;42(2):191–228. https://doi.org/10.1446/rcs.v42n2.74809.

Bonilla-Aguilar K, Bernabe-Ortiz A. Association between total available nutritional quality and food expenditure in Peruvian households, 2019–2020. Cad Saude Publica. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311xen021923.

Almeida AN, Azzoni CR. Custo de vida comparativo das regiões metropolitanas brasileiras: 1996–2014. Estudos Econômicos (São Paulo). 2016;46(1):253–76. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-416146128aaa.

Deaton A. The Analysis of Household Surveys A Microeconometric Approach to Development Policy Reissue Edition with a New Preface.

Von Grebmer K, Bernstein J, Wiemers M, Reiner L, Bachmeier M, Hanano A, et al. Global Hunger Index the power of youth in shaping food systems. A Peer-Reviewed Publication. 2023.

ECLAC. Trade Outlook for Latin America and the Caribbean 2024. Reconfiguration of global trade and options for regional recovery International. 2024.

Kirkpatrick S, Tarasuk V. The relationship between low income and household food expenditure patterns in Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2012;16(4):653–8.

Macino L, Guthrie J, ver Ploeg M, Lin B. Nutritional quality of foods acquired by Americans: Findings from USDA’s National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey. 2018.

Béné C, Bakker D, Chavarro MJ, Even B, Melo J, Sonneveld A. Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Glob Food Sec. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100575.

FAO, FIDA, OPS, PMA, UNICEF. Panorama regional de la seguridad alimentaria y nutricional - América Latina y el Caribe 2022. FAO; IFAD; PAHO; WFP; UNICEF; 2023. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3859es

Bafowaa BY, Leschewski AM. COVID-19 relief receipt and US household food expenditures. AJPM Focus. 2024;3(5):100265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2024.100265.

Sánchez-Ortiz NA, Colchero MA. Changes in food and beverage purchases associated with the coronavirus disease pandemic in Mexico. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024;124(4):521-530.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2023.07.026.

Swinnen J, McDermott J. COVID-19 and global food security. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133762

Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Balance de Gestión Integral: Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas. 2019.

Ministerio de Hacienda de Chile. Evaluación programa nacional de alimentación complementaria y programa de alimentación complementaria del adulto mayor. 2020.

Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Bases técnicas bebida láctea años dorados. 2011.

Hidrobo M, Hoddinott J, Peterman A, Margolies A, Moreira V. Cash, food, or vouchers? Evidence from a randomized experiment in northern Ecuador. J Dev Econ. 2014;107:144–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.11.009.

CEPES, La Revista Agraria. Seguridad alimentaria en el Perú. Compendio de artículos publicados en La Revista Agraria 2010–2015. 2016.

Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural de Colombia. Plan Nacional para la Promoción de la Comercialización de la Producción de la Economía Campesina, Familiar y Comunitaria. 2019.

Funding

This research was funded by the project 10-220098-70 from the Ministerio de Agricultura de Chile.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.D. Methodology: A.D., J.G., M.J., M.B. Validation: J.G. Formal analysis: A.D., J.G. Data curation: A.D. Writing-original draft: A.D., J.G. Writing-review and editing: J.G., M.J., M.B. Visualization: A.D. Supervision: J.G. All co-authors reviewed the final version and approved the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval consent to participate

This study involved the participation on human subjects. The protocol was approved by the Department of Technical Subdirection of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística and the Expert Committee of the EPF study, adhering the INE Ethics code, Chilean government guidelines and recognized international standards, including the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In this study informed consent was sought from all individual participants (respondents) included in the study. The survey was conducted with the household’s primary representative, and all participants were over 16 years of age. They were informed that the survey was anonymous, they were free to discontinue the survey at any point and they were aware of any benefits and risks associated with the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donoso, A., González, J., Betancur, M. et al. Deciphering the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security across different socioeconomic strata in Chile. Discov Food 5, 69 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-025-00339-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-025-00339-0