Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected mental health, with many survivors experiencing psychological challenges, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This study assessed PTSD symptoms and Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) among 62 individuals recovering from COVID-19 infection, all of whom were under the care of the Department of Pneumonology, Oncology, and Allergology at the Medical University of Lublin. Results revealed that 40.32% of participants exhibited PTSD symptoms. Key predictors of PTSD severity included cognitive symptoms and post-COVID self-rated health, with cognitive symptoms positively associated and self-rated health negatively associated with PTSD severity. A positive correlation was also found between PTSD severity and PTG, suggesting that while individuals endure significant psychological distress, they may also experience personal growth, such as enhanced resilience and a redefined life perspective. These findings highlight the dual psychological impact of COVID-19 infection, particularly for individuals with preexisting pulmonary conditions. They underscore the importance of holistic, integrated care that addresses both the reduction of PTSD symptoms and the promotion of meaningful psychological growth in COVID-19 survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic has profoundly impacted society’s mental health, with individuals who contracted COVID-19 particularly vulnerable to its physical and psychological effects. Among these individuals, patients with pre-existing pulmonary conditions represent a group that may face a compounded risk due to the interplay of chronic illness, COVID-19 complications, and psychological burden1. Research consistently shows that many COVID-19 survivors, particularly those with severe cases or comorbidities, experience persistent mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Estimates suggest that 12.4–37% of COVID-19 survivors exhibit symptoms of PTSD2,3,4. A study by Bo et al. reported that approximately 96.2% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 showed significant PTSD symptoms one month after discharge5. These findings underscore the urgency of addressing mental health outcomes, particularly in patients with heightened vulnerability, such as those with pre-existing pulmonary conditions.

The exacerbation of physical health challenges in this population may amplify the psychological burden. Pulmonary patients recovering from COVID-19 often experience lingering symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, and impaired lung function, collectively termed post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These symptoms have been linked to significant reductions in quality of life and increased psychological distress6,7. For instance, dyspnea—a common symptom in both COVID-19 and chronic pulmonary conditions—has been independently associated with heightened levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms8. Moreover, studies have noted that the physical strain of pulmonary rehabilitation can trigger or worsen PTSD symptoms, particularly in patients with a history of intensive care unit (ICU) admission or mechanical ventilation9,10.

According to the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), PTSD emerges following exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. It is characterized by distinct symptom clusters: re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and heightened arousal, which persist for more than one month after the traumatic event11. Patients exhibiting these symptoms often struggle to manage without intervention; untreated PTSD can lead to ongoing psychological distress and adversely impact various aspects of life.

Interestingly, some individuals not only endure negative consequences from traumatic experiences but also undergo positive changes, a phenomenon known as post-traumatic growth (PTG). Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) define PTG as the “positive change that the individual experiences as a result of the struggle with a traumatic event.” PTG encompasses improved self-perception, enhanced interpersonal relationships, and a transformed life philosophy. These positive changes can manifest as increased resilience to stress, a heightened appreciation for life and loved ones, and shifts in religious or spiritual beliefs12.

This study aims to investigate the prevalence and intensity of PTSD symptoms in pulmonary patients who have recovered from COVID-19 and explore their association with both physical and psychological factors. Additionally, the study seeks to assess the occurrence of PTG and its relationship with other variables. This study is particularly timely given the ongoing consequences of the pandemic and the increasing number of Covid-19 survivors experiencing long-term effects. By focusing on this specific patient group, the research aims to provide insights that could inform targeted interventions for both PTSD and PTG in post-COVID-19 pulmonary care.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

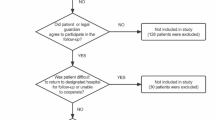

This cross-sectional study was conducted among patients under the care of the Department of Pneumonology, Oncology, and Allergology in Lublin, as well as the Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Clinic. A total of 90 individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 were initially recruited. Ultimately, 62 patients, aged 25–80, who fully and correctly completed all research instruments were included in the analysis. Inclusion criteria were being in outpatient care of the department, a history of COVID-19 infection, declaring no other potentially traumatic events, the ability to provide informed consent, and the completion of the specified questionnaires. The patients were asked to take part in the study when they came for a control visit approximately 6 months after recovering from COVID-19 infection.

All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Lublin, in Resolution No. KE-0254/97/2021, after reviewing the complete documentation and in accordance with its principles (Good Clinical Practice, GCP), issued a positive opinion on the presented research project. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Instruments

-

Author’s Questionnaire: This instrument collected demographic data and additional information regarding circumstances related to the COVID-19 illness. There were also questions about co-morbid illnesses.

-

Self-Rated Health (SRH): Self-rated health after COVID-19 infection was assessed by asking the respondents: “In general, how would you rate your health ?” with the possible choices being “very good” (5), “good” (4), “moderate” (3), “bad” (2) or “very bad” (1). SRH before COVID-19 infection was assessed by a similar question: „In general, how would you rate your health before COVID-19 infection?”, with the same answers to pick from. The subjective evaluation assessed by SRH has been shown to be a reliable predictor of various health outcomes, including mortality and morbidity. Its simplicity and effectiveness make it a valuable tool in both clinical practice and public health research13.

-

Revised Impact of Event Scale (IES-R): Developed by Weiss and Marmar, this self-assessment tool consists of 22 items designed to measure subjective stress caused by a traumatic event14. The scale demonstrates high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha values typically ranging from 0.87 to 0.95 for the total scale and subscales (intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal)15. The IES-R has strong construct validity, as it correlates well with other measures of trauma-related symptoms such as the PTSD Checklist (PCL)16. Additionally, it exhibits criterion validity, being effective in distinguishing individuals with and without PTSD17. The Polish adaptation of the IES-R was conducted by Zygfryd Juczyński and Nina Ogińska-Bulik, and its psychometric evaluation also demonstrated high internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale is 0.9218. It also represents strong construct validity: Confirmatory factor analyses supported the three-factor structure of the scale, consistent with the theoretical model of PTSD19.

-

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI): Constructed by Tedeschi and Calhoun, this scale assesses positive personality changes following a traumatic event12. The PTGI has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values typically above 0.90 for the total scale and subscales (e.g., personal strength, appreciation of life, and spiritual change)20. The scale demonstrates robust construct validity, showing significant correlations with measures of resilience, life satisfaction, and coping strategies21. Factor analysis supports its five-factor structure, and it has shown good discriminant validity, separating posttraumatic growth from general psychological well-being22. The original PTGI demonstrates excellent psychometric properties, including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.90 for the total scale; subscale alphas ranging from 0.83 to 0.91)20. It also shows good test-retest reliability (r > 0.70) and construct validity, supported by factor analyses confirming its five-dimensional structure21. The Polish adaptation of the PTGI, conducted by Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński (2010), also demonstrates high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale at 0.93 and subscale alphas ranging from 0.70 to 0.89. Construct validity is supported by factor analyses, which confirm the alignment with the original theoretical framework, and strong correlations with related constructs such as resilience and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Test-retest reliability over a six-week period exceeds 0.80, further demonstrating its stability23.

-

HADS – The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a widely used self-report tool designed to assess anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric hospital settings24. It consists of 14 items, divided equally between anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) subscales, with each item scored on a scale from 0 to 325. The HADS is known for its strong psychometric properties, including good internal consistency (with Cronbach’s alpha values typically above 0.80 for each subscale)26 and robust construct validity27.

-

Scales for the Measurement of Mood and Six Emotions by Bogdan Wojciszke is a tool that includes three scales measuring mood (general, positive and negative) and six scales measuring frequency of discrete emotions ( joy, live, anger, fear, sadness and guilt). The scale demonstrates high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha above 0.70 for most subscales) and good validity, confirmed through numerous validation studies28.

Procedure

Participants were asked to complete the above instruments, ensuring that they provided a comprehensive view of their mental health status and coping mechanisms post-COVID-19 infection. The condition for conducting the study was also to obtain the patient’s informed consent. Data collection focused on identifying the presence and severity of PTSD symptoms, as well as the occurrence and extent of PTG. In both cases patients were asked if there were other potentially traumatic events other than going through COVID 19 infection.

Statistical analysis

The study group was characterized using descriptive statistics. Qualitative variables were described using frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were described using the minimum (Min.), maximum (Max.), mean (M), and standard deviation (SD). Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the co-occurrence of post-traumatic stress symptoms, the number of illnesses, self-rated health status, anxiety severity, depression, irritability, post-traumatic growth, positive emotions, and negative emotions. Regression analysis was applied to evaluate the explanatory variables for PTSD symptom severity. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc.).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 62 patients who had recovered from COVID-19 participated in this study, including 38 women (61.29%) and 24 men (38.71%). The participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 80 years, with a mean age of 59 years and a standard deviation of 13 years. Nearly one-third of the respondents resided in cities with populations between 100,000 and 500,000 (n = 19, 30.65%). About one-quarter lived in rural areas (n = 16, 25.81%) or in cities with populations between 10,000 and 100,000 (n = 16, 25.81%). Seven participants (11.29%) lived in towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, while four respondents (6.45%) lived in cities with populations exceeding 500,000.

Educational attainment varied, with the largest group holding higher education degrees (n = 24, 38.71%), followed by those with secondary education (n = 14, 22.58%), vocational education (n = 13, 20.97%), and primary education (n = 3, 4.84%).

More than half of the patients were married (n = 35, 56.45%), while the rest were widowed (n = 10, 16.12%), single (n = 9, 14.52%), divorced (n = 4, 6.45%), or in relationships (n = 4, 6.45%).

The majority were retirees or pensioners (n = 28, 45.16%), followed by employed individuals (n = 26, 41.94%), farm workers (n = 5, 8.07%), and those who were unemployed or students (n = 3, 4.84%).

Psychological characteristics

Descriptive statistics of psychological variables are presented in Table 1.

Health status pre- and post-COVID-19

Retrospective self-assessment of health before contracting COVID-19 showed most respondents rated their health as “good” (n = 45, 72.58%), with others rating it as “very good” or “moderate”. Post-COVID-19 self-assessments dropped, with most rating their health as “moderate” (n = 29, 46.77%) or “good” (n = 25, 40.32%), with fewer rating it as “bad” or “very good” (Table 2).

Chronic conditions and COVID-19 complications

The largest group of respondents had one chronic condition (n = 26, 41.94%), with others having multiple conditions: two (n = 17, 27.42%), three (n = 2, 3.23%), four (n = 4, 6.45%), and five (n = 2, 3.23%). Hospitalization due to COVID-19 was reported by 20 respondents (32.26%). Post-COVID symptoms were reported by 43 respondents (69.35%), including somatic complaints (n = 40, 64.52%) and cognitive problems (n = 19, 30.65%). Psychological help was utilized by 10 respondents (16.13%) before COVID-19 and by 5 (8.06%) post-COVID-19. Psychiatric help was sought by 9 respondents (14.52%) pre-COVID-19 and by 4 (6.45%) post-COVID-19. Positive PTSD screening was found in 25 respondents (40.32%).

Correlation analysis

The severity of PTSD symptoms was negatively correlated with the number of diseases, post-COVID self-assessment of health, and the intensity of positive emotions. PTSD severity was positively correlated with anxiety, irritability, the severity of negative emotions, and post-traumatic growth (Table 3).

Regression analysis

Due to the small sample size, it was not possible to include all potentially relevant variables in the regression models explaining PTSD severity and post-traumatic growth intensity. In the model explaining PTSD severity, the decision was made to include variables related to the participants’ health status. This decision was based on the assumption that variables describing the respondents’ mental state, although strongly associated with PTSD severity, are more likely to coexist with rather than explain its severity.

The model analyzing PTSD severity included four post-COVID health status variables: the number of diseases, post-COVID self-assessment of health, the presence of somatic symptoms, and cognitive symptoms. The first two variables were significantly correlated with PTSD severity, suggesting that they may play an important role in the model. The remaining two variables are dichotomous and were included in the model based on the researchers’ clinical experience.

This model was statistically significant (F(4,55) = 4.61, p < 0.01) and explained 20% of the variance in PTSD severity (R²=0.25, Adjusted R²=0.20). Significant predictors were cognitive symptoms (b*=0.35, p < 0.01) and post-COVID self-rated health (b*=-0.36, p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Regression analysis was also used to analyze the relationship between the severity of post-traumatic development and variables describing the respondents’ mental state at the time of the study. The researchers decided to include all psychological variables that were statistically significantly correlated with post-traumatic growth intensity in the correlation analysis. The model analyzing post-traumatic growth included irritability, PTSD severity, intensity of positive emotions, and intensity of negative emotions. This model was statistically significant (F(4,57) = 5.97, p < 0.001) and explained 25% of the variance in post-traumatic growth (R2 = 0.30, Adjusted R2 = 0.25). PTSD severity (b*=0.58, p < 0.001) was the significant predictor (Table 5).

Discussion

Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms

The findings of this study underscore the substantial psychological burden faced by individuals recovering from COVID-19, with a notable proportion of participants reporting symptoms consistent with PTSD. This aligns with prior research highlighting the high prevalence of PTSD among COVID-19 survivors. For example, Mazza et al. identified a 30.2% prevalence of PTSD in this population, while Liu et al. reported a prevalence of 23.6%, emphasizing pre-existing health conditions and the severity of infection as key predictors of PTSD symptoms4,29. Similarly, research in Frontiers in Psychiatry found PTSD prevalence rates ranging from 12.4 to 28% among COVID-19 survivors30.

Our study observed a PTSD prevalence of 40.32%, which is notably higher than these earlier findings. This discrepancy could be partly explained by the unique characteristics of our sample, composed of pulmonary patients. Previous research suggests that individuals with chronic respiratory conditions are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress, including PTSD, anxiety, and depression, due to the interplay of physical health challenges, reduced lung function, and fear of respiratory deterioration31,32. This is consistent with findings from Bendstrup et al., who demonstrated elevated psychological morbidity among patients with interstitial lung disease33.

Moreover, the higher prevalence in our study may also reflect the specific context of COVID-19, where pulmonary patients often experience more severe illness trajectories and prolonged recovery times. Studies have shown that the severity of respiratory symptoms and hospitalization (including ICU admission and mechanical ventilation) are strong predictors of PTSD in COVID-19 survivors34,35. Pulmonary patients may also face heightened health anxiety and uncertainty about long-term respiratory outcomes, further exacerbating psychological distress. Additionally, research by Bo et al. (2021) on SARS and MERS survivors highlighted the long-lasting psychological effects of respiratory pandemics, suggesting that pulmonary complications and isolation during illness contribute significantly to PTSD prevalence36. This is particularly relevant in the COVID-19 context, where social isolation during illness and fears of reinfection may have compounded psychological distress among our participants. Finally, it is crucial to consider the bidirectional relationship between psychological stress and pulmonary health. Stress-induced inflammation and respiratory dysregulation may amplify the physical symptoms of pulmonary diseases, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates psychological distress37. Addressing these factors through integrated psychological and medical care is vital for supporting recovery in this population.

Cognitive symptoms and PTSD

The cognitive symptoms identified in our study as predictors of PTSD severity align with findings from other research. Qi et al. (2020) reported significant psychological morbidities and cognitive deficits among COVID-19 patients, suggesting that these cognitive symptoms play a crucial role in the development and persistence of PTSD38. Similarly, Bonazza et al. (2022) found that cognitive issues, along with anxiety and depression, were prevalent among COVID-19 survivors and contributed to PTSD symptoms six months after discharge39. The link between cognitive symptoms and PTSD severity is also supported by Taquet et al.‘s findings, which highlighted that cognitive deficits were common in those with severe post-COVID infection PTSD symptoms40. Further supporting this association, Logue et al. (2021) found that 56.7% of individuals with post–COVID-19 condition experienced at least one cognitive symptom daily, significantly more than those without the condition. These cognitive impairments were linked to difficulties in daily functioning and increased psychological distress41.

It is worth noting, that patients with pulmonary diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or interstitial lung disease (ILD), may experience additional cognitive decline due to a combination of systemic inflammation, hypoxemia, and comorbidities. Studies suggest that chronic hypoxemia, common in pulmonary diseases, negatively impacts brain function, particularly in areas related to memory, attention, and executive functioning42. A study by Cleutjens et al. (2017) highlighted that nearly 36% of COPD patients demonstrated clinically significant cognitive impairments, which could further exacerbate psychological symptoms such as PTSD43. Moreover, chronic respiratory diseases are associated with heightened levels of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, which are hypothesized to contribute to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline44. Pulmonary patients recovering from COVID-19 may face an even greater risk due to the synergistic effects of prolonged hypoxia, COVID-19-related inflammation, and post-viral fatigue. This combination could exacerbate pre-existing vulnerabilities to cognitive dysfunction and amplify PTSD symptoms.

These findings underscore the importance of assessing and addressing cognitive symptoms in pulmonary patients, particularly those who have experienced a COVID-19 infection or exhibit PTSD symptoms. Early interventions, such as cognitive rehabilitation or tailored psychological therapies, could play a role in mitigating the impact of cognitive decline on overall mental health and recovery outcomes.

Other PTSD correlates—irritability and self-rated health

Our research has demonstrated a positive correlation between the severity of PTSD symptoms and patient irritability, consistent with the findings of Zhou et al. (2021)45. This association can be partially attributed to the heightened arousal characteristic of PTSD. Additionally, irritability may stem from underlying anxiety or serve as a manifestation thereof46.

Our study revealed that self-rated health, both before and after COVID-19 infection, plays a significant role in predicting the severity of PTSD symptoms. Participants who perceived their post-COVID health as poor were more likely to report severe PTSD symptoms. These findings align with research by Taquet et al. (2021), which identifies subjective health perceptions as a critical determinant of psychological well-being47. Poor self-rated health may reflect both physical and emotional difficulties, underscoring the need for a holistic approach to care that addresses both physical recovery and mental health. It is also worth noting that some studies emphasize that self-rated health can serve as a predictor of life expectancy48.

PTSD and post-traumatic growth

The results of this study revealed a positive correlation between the severity of PTSD symptoms and the level of post-traumatic growth (PTG), indicating that individuals with higher PTSD symptom severity also reported greater levels of perceived personal growth. This co-occurrence of PTSD and PTG is not new and has been documented in prior research. Vazquez et al. found that individuals experiencing significant post-traumatic stress in the context of COVID-19 also reported signs of PTG, suggesting that grappling with intense psychological experiences can foster self-reflection and lead to positive changes, such as enhanced resilience or shifts in life priorities49. Similarly, Adjorlolo et al. observed high levels of both PTSD and PTG in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, with PTG being particularly associated with reflective processes and the development of a new life perspective50.

However, as Maercker and Zoellner (2006) proposed in their “Janus Face” model, PTG may not always represent unambiguous positive change. This model distinguishes between constructive growth, involving genuine, enduring improvements (e.g., greater resilience, improved relationships, or redefined life values), and illusory growth, which reflects a subjective sense of progress that may serve as a defensive mechanism but does not necessarily translate into lasting emotional or social functioning improvements51. According to the above model, positive correlation between PTSD and PTG found in our studies could be interpreted in multiple ways. High levels of PTSD symptoms in our cohort might indicate that reported growth represents an attempt to assign meaning to adverse events, rather than genuine psychological improvement.

Zhou et al. (2021) emphasize that the unpredictable nature of the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified existential concerns, making individuals more likely to reframe traumatic experiences as part of a coping mechanism. Their findings suggest that PTG reported in pandemic contexts may, at times, mask underlying distress, as individuals attempt to regain a sense of control through perceived growth52. Similarly, Liu (2021) highlighted that individuals who reported PTG during the pandemic often demonstrated increased stress levels when confronted with new uncertainties, indicating that PTG may function as a temporary psychological shield rather than a sign of sustained growth53.

Smith (2023), in a systematic review of post-pandemic psychological responses, further reinforces this dual perspective by underscoring that some individuals may display “illusory optimism” as a coping strategy soon after trauma. Smith’s review supports the notion that PTG reported in the early stages of recovery may not reflect long-term changes but rather a mechanism for reducing immediate emotional distress. This highlights the importance of assessing PTG longitudinally to distinguish between adaptive reappraisal and enduring personality or value changes54.

Despite the ambiguity surrounding PTG, studying this phenomenon is essential for understanding the recovery process more comprehensively. PTG provides valuable insights into the interplay between suffering and the potential for positive change following trauma. Moreover, as Vasquez et al. (2021) argue in their analysis, different frameworks for understanding PTG—such as those emphasizing coping strategies or deeper transformations—do not necessarily exclude each other but may instead represent complementary stages or dimensions of growth following trauma55. Even when PTG serves as a defense mechanism, it can act as a foundation for deeper, lasting growth. However, it is crucial for psychologists and professionals working with individuals displaying PTG to carefully assess whether these symptoms may reflect unrealistic optimism or denial. Such coping mechanisms could potentially hinder the proper processing of trauma and obstruct effective recovery. Targeted therapeutic approaches may help transform illusory aspects of PTG into authentic, constructive outcomes56,57. By integrating PTG into research and clinical practice, as suggested by Maercker and Zoellner, it is also possible to move beyond the focus on trauma-related deficits. This broader perspective enables a more balanced approach, which acknowledges both the pain of trauma and the potential for personal growth it may bring.

Conclusions

This study highlights the significant psychological and cognitive challenges faced by COVID-19 survivors, particularly among pulmonary patients. The high prevalence of PTSD symptoms observed underscores the urgent need for integrated care addressing both psychological and physical health issues. Cognitive impairments and poor self-rated health emerged as key predictors of PTSD severity, emphasizing the importance of interventions such as cognitive rehabilitation and psychological therapies to support recovery.

The positive correlation between PTSD severity and post-traumatic growth (PTG) suggests that while traumatic experiences amplify distress, they can also foster personal growth. However, it is important to recognize that some reported growth may reflect adaptive coping mechanisms rather than genuine psychological improvement. Therapeutic interventions should aim to transform such coping into meaningful, enduring change, promoting resilience and improved well-being.

This study underscores the value of a holistic, multidisciplinary approach to post-COVID care that integrates mental health and physical recovery strategies. Further research is needed to explore the long-term interplay between PTSD and PTG, focusing on how tailored interventions can enhance recovery outcomes. These findings contribute to the growing understanding of the pandemic’s mental health impacts and provide practical insights for improving care for COVID-19 survivors, particularly those with preexisting pulmonary conditions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Zhang, J. J. et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 75 (7), 1730–1741 (2020).

Chamberlain, S. R., Grant, J. E., Trender, W., Hellyer, P. & Hampshire, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in COVID-19 survivors: online population survey. B J. Psych Open. 7 (2), 1 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in COVID-19 survivors 6 months after hospital discharge: an application of the conservation of resource theory. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 773106 (2022).

Mazza, M. G. et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 89, 594–600 (2020).

Bo, H. X. et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol. Med. 51, 1052–1053 (2021).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27 (4), 601–615 (2021).

Carfi, A., Bernabei, R. & Landi, F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 324 (6), 603–605 (2020).

von Leupoldt, A. & Dahme, B. Psychological aspects in the perception of dyspnea in obstructive pulmonary diseases. Respir. Med. 101 (3), 411–422 (2007).

Halpin, S. J. et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 372, 693 (2021).

Davydow, D. S., Gifford, J. M., Desai, S. V., Needham, D. M. & Bienvenu, O. J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 30 (5), 421–434 (2009).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress. 9, 455–471 (1996).

Idler, E. L. & Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 38 (1), 21–37 (1997).

Weiss, D. S. & Marmar, C. R. The impact of event scale—revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD (eds Wilson, T. M. & Keane, T. M.). Guilford Press, 399-411 (1997).

Creamer, M., Bell, R. & Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 41 (12), 1489–1496 (2003).

Asukai, N. et al. Reliability and validity of the japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J. Nerv. Mental Disease. 190 (3), 175–182 (2002).

Sundin, E. C. & Horowitz, M. J. Impact of event scale: psychometric properties. Br. J. Psychiatry. 180 (3), 205–209 (2002).

Juczyński, Z. & Ogińska-Bulik, N. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu I Radzenia Sobie Ze Stresem . Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych (2009).

Ogińska-Bulik, N. & Juczyński, Z. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Polish version of the IES-R. Folia Physiol. 14, 39–54 (2010).

Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 15 (1), 1–18 (2004).

Linley, P. A. & Joseph, S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J. Trauma. Stress. 17 (1), 11–21 (2004).

Powell, S., Rosner, R., Butollo, W., Tedeschi, R. G. & Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth after war: a study with former refugees and displaced people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Clin. Psychol. 59 (1), 71–83 (2003).

Ogińska-Bulik, N. & Juczyński, Z. Measurement of posttraumatic growth in the Polish population. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 42 (3), 129–135 (2011).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 67 (6), 361–370 (1983).

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T. & Neckelmann, D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52 (2), 69–77 (2002).

Mykletun, A., Stordal, E. & Dahl, A. A. Hospital anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses, and internal consistency in a large population. Br. J. Psychiatry. 179 (6), 540–544 (2001).

Herrmann, C. International experiences with the hospital anxiety and Depression Scale—A review of validation data and clinical results. J. Psychosom. Res. 42 (1), 17–41 (1997).

Wojciszke, B. & Baryła, W. Scales fot the measurement of mood and six emotions. Psychol. J. 11 (1), 31–47 (2004).

Liu, D. et al. Risk factors associated with mental illness in hospital discharged patients infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Psychiatry Res. 291, 113297 (2021).

Janiri, D. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after severe COVID-19 infection. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 773106 (2021).

Yohannes, A. M. & Alexopoulos, G. S. Depression and anxiety in patients with chronic respiratory diseases: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Int. J. COPD. 9, 871–881 (2014).

Santos, L. R. M., Holanda, M. A., Medeiros, M. M. B., Lima, J. N. & Barbosa, R. C. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (19), 6944 (2020).

Bendstrup, E. et al. Psychological burden in patients with interstitial lung disease. Front. Med. 6, 53 (2019).

Shangguan, F., Wang, R., Quan, X. & Zhang, H. Anxiety, depression, and PTSD following COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional study in a sample of Chinese people. J. Affect. Disord. 282, 312–314 (2021).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: who will be the high-risk group? Psychol. Med. 51 (2), 1–2 (2020).

Bo, H. X. et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitudes toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol. Med. 51 (6), 1052–1053 (2021).

Rosenkranz, M. A., Davidson, R. J. & Stein, J. H. The impact of stress on lung health and inflammation: mechanisms and pathways. Ann. Behav. Med. 54 (5), 402–414 (2020).

Qi, W., Zhang, D. & Zhang, L. Psychological morbidities and cognitive deficits in COVID-19 patients. J. Affect. Disord. 276, 735–742 (2020).

Bonazza, F. et al. Anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: a 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychology 36 (2), 113–121 (2022).

Taquet, M. et al. Cognitive impairment and PTSD following COVID-19 infection: evidence from a large database study. Lancet Psychiatry. 8 (5), 386–394 (2021).

Logue, J. K. et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (2), 1 (2021).

Dodd, J. W. Lung disease as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 7 (1), 32 (2015).

Cleutjens, F. A. et al. Cognitive-pulmonary interplay in COPD: implications for clinical practice. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 195 (2), 181–188 (2017).

Yaffe, K. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and inflammation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59 (10), 1813–1818 (2011).

Zhou, X. et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and irritability in COVID-19 survivors: a longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 295, 123–130 (2021).

Leibenluft, E. et al. The interaction of irritability and anxiety on emotional responding and emotion regulation: a functional MRI study. Psychol. Med. 44 (9), 1931–1941 (2014).

Taquet, M. et al. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: a 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 18 (9), 1 (2021).

Vie, T. L., Hufthammer, K. O., Meland, E., Breidablik, H. J. & Mykletun, A. Self-rated health as a predictor of mortality: a cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and known risk factors. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43 (4), 1097–1106 (2014).

Vazquez, C. et al. Post-traumatic growth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a model of resilience under stress. Front. Psychol. 12, 1 (2021).

Adjorlolo, S. et al. PTSD and PTG in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: interplay of trauma and growth. J. Clin. Psychol. 78 (3), 435–450 (2022).

Maercker, A. & Zoellner, T. The Janus Face of self-perceived growth: toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Inq. 17 (1), 41–48 (2006).

Zhou, S. J. et al. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: a review. Front. Psychiatry 11 (2021).

Liu, C. H., Zhang, E., Wong, G. T. F., Hyun, S. & Hahm, H. C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adults. Psychiatry Res. 295, 113–118 (2021).

Smith, J. A., Brown, T. M. & Williams, K. Post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth in COVID-19 survivors: a systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 28 (5), 765–789 (2023).

Vazquez, C. et al. Post-traumatic growth and stress-related responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in a National Representative Sample: the role of positive core beliefs about the World and others. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 2915–2935 (2021).

Ochoa, C., Casellas-Grau, A., Vives, J., Font, A. & Borràs, J. M. Positive psychotherapy for distressed cancer survivors: posttraumatic growth facilitation reduces posttraumatic stress. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 17 (1), 28–37 (2017).

Gori, A., Topino, E., Sette, A. & Cramer, H. Pathways to post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: Moderated mediation and single mediation analyses with resilience, personality, and coping strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 692–700 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. wrote the main manuscript text, created the research project and coordinated its execution. B.M. participated in the creation of the research concept and also collected all the data. A.F. conducted the statistical analysis along with the description. P.M. entered and adjusted all the data for the calculations. M.S. participated in the creation of the research project concept, reviewed the conducted studies and the main text, making substantive corrections. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milanowska, J., Mackiewicz, B., Aftyka, A. et al. Posttraumatic stress and growth in pulmonary patients recovered from COVID-19. Sci Rep 15, 3850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88405-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88405-6